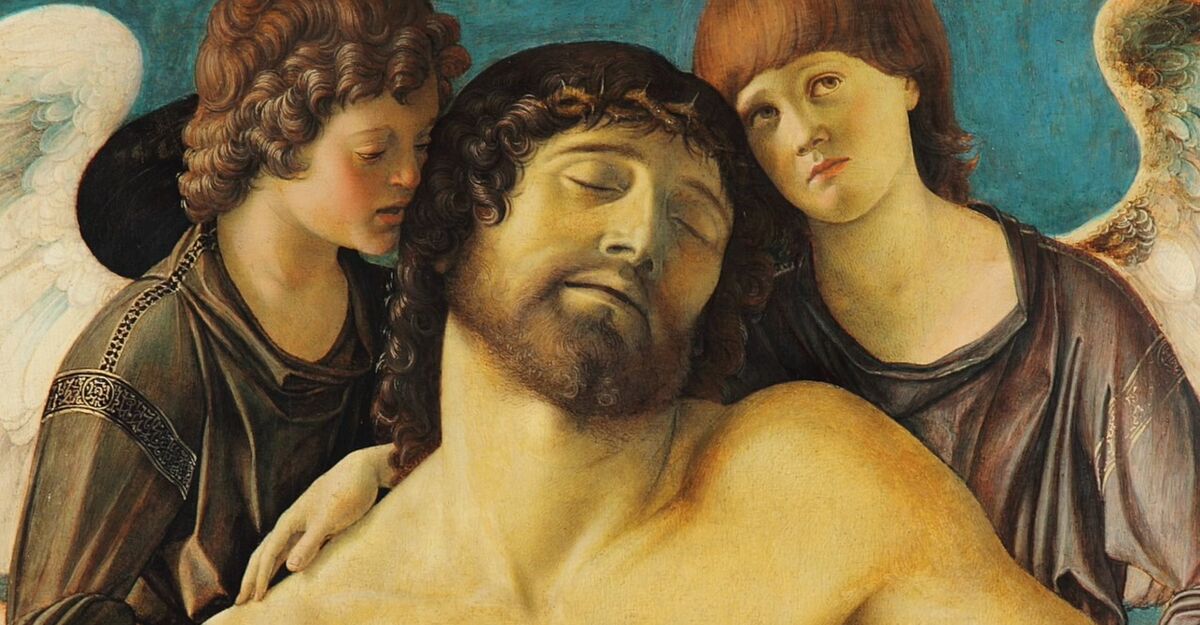

A sweeping historical review challenges claims that Jesus was a myth, showing through early documents, hostile Roman and Jewish records, and the explosive rise of Christianity in Jerusalem that a real man’s execution triggered a movement so powerful it still unsettles history today.

For centuries, the question has lingered at the edge of Western history: was Jesus of Nazareth a real man, or merely a myth created by an early religious movement seeking authority and meaning? In recent years, that question has resurfaced with renewed intensity, fueled by internet skepticism and popular books arguing that Jesus was copied from pagan gods or invented decades after the fact.

Yet a growing body of historical analysis is pushing back, not with sermons or theology, but with documents, dates, names, and events that place Jesus firmly in the real world of first-century Palestine.

Historians point first to the earliest written sources.

Letters attributed to Paul of Tarsus, widely dated between AD 48 and 62, were written roughly 20 to 30 years after Jesus’ execution.

In these letters, Paul refers to Jesus as a real person who was crucified, buried, and known personally by individuals Paul later met, including Peter and James, identified explicitly as Jesus’ brother.

These writings circulated while eyewitnesses—both supporters and opponents—were still alive, making wholesale invention historically implausible.

Crucially, references to Jesus are not confined to Christian texts.

Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, writing in Rome around AD 93, mentions Jesus as a teacher who was executed under the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate.

While scholars debate later Christian edits to Josephus’ text, most agree a core reference to Jesus is authentic.

Roman sources echo the same reality.

Around AD 112, Pliny the Younger, governor of Bithynia, wrote to Emperor Trajan describing Christians who worshipped Christ “as a god” and refused to curse his name, even under threat of execution.

Earlier still, Roman historian Tacitus recorded that “Christus” was executed during the reign of Tiberius, again under Pontius Pilate.

None of these writers were sympathetic to Christianity.

None denied Jesus existed.

The social shockwaves following Jesus’ death also demand explanation.

According to multiple independent accounts, his followers fled Jerusalem in fear after the crucifixion, convinced their movement was finished.

Yet within weeks, those same individuals were publicly proclaiming that Jesus had been raised from the dead—doing so in Jerusalem itself, the very city where Roman and Jewish authorities could have easily disproven the claim by producing a body.

Instead, the movement grew rapidly, drawing persecution rather than power.

Historians note that people may die for a belief they think is true, but rarely for something they know to be false.

Another striking piece of evidence lies in early Christian creeds.

Embedded within Paul’s letters are short, structured statements of belief that scholars date to within five to ten years of the crucifixion.

These creeds summarize Jesus’ death, burial, resurrection, and post-death appearances in a form already standardized far too early for legendary embellishment to develop.

The language suggests these beliefs were not evolving myths but inherited traditions.

Named eyewitnesses further anchor the story in history.

Figures such as Peter, John, James, and Mary Magdalene appear across multiple independent sources, Christian and non-Christian alike.

James, once a skeptic according to early accounts, later became a leader of the Jerusalem church and was executed around AD 62, a fact also recorded by Josephus.

These are not anonymous symbols, but historically traceable individuals operating in known places at known times.

Perhaps most surprising to historians is the transformation of Jewish religious practice that followed.

For over a thousand years, Sabbath observance on Saturday was central to Jewish identity.

Yet within a single generation, early Jewish Christians shifted their primary day of worship to Sunday, commemorating the day they believed Jesus rose from the dead.

Such a radical change, scholars argue, demands a powerful historical catalyst.

Together, these converging lines of evidence form a cumulative case that challenges the idea of Jesus as myth.

While debates continue about the interpretation of miracles or theology, the existence of Jesus as a historical figure is widely accepted among scholars, including those with no religious commitment.

The real question, historians increasingly argue, is no longer whether Jesus lived—but what explains the impact he left behind.

The documents remain.

The names remain.

The controversy remains.

And two thousand years later, the evidence still refuses to disappear.

News

New Zealand Wakes to Disaster as a Violent Landslide Rips Through Mount Maunganui, Burying Homes, Vehicles, and Shattering a Coastal Community

After days of relentless rain triggered a sudden landslide in Mount Maunganui, tons of mud and rock buried homes, vehicles,…

Japan’s Northern Stronghold Paralyzed as a Relentless Snowstorm Buries Sapporo Under Record-Breaking Ice and Silence

A fierce Siberian-driven winter storm slammed into Hokkaido, burying Sapporo under record snowfall, paralyzing transport and daily life, and leaving…

Ice Kingdom Descends on the Mid-South: A Crippling Winter Storm Freezes Mississippi and Tennessee, Leaving Cities Paralyzed and Communities on Edge

A brutal ice storm driven by Arctic cold colliding with moist Gulf air has paralyzed Tennessee and Mississippi, freezing roads,…

California’s $12 Billion Casino Empire Starts Cracking — Lawsuits, New Laws, and Cities on the Brink

California’s $12 billion gambling industry is unraveling as new laws and tribal lawsuits wipe out sweepstakes platforms, push card rooms…

California’s Cheese Empire Cracks: $870 Million Leprino Exit to Texas Leaves Workers, Farmers, and a Century-Old Legacy in Limbo

After more than a century in California, mozzarella giant Leprino Foods is closing two plants and moving $870 million in…

California’s Retail Shockwave: Walmart Prepares Mass Store Closures as Economic Pressures Collide

Walmart’s plan to shut down more than 250 California stores, driven by soaring labor and regulatory costs, is triggering job…

End of content

No more pages to load