Set on an 1827 Louisiana plantation, this report reveals how a gravely ill enslaved girl was sold for just two coins to rid owners of a “liability,” only to die days later after uttering words that spread through the quarters and became a lasting symbol of injustice—an outcome that leaves a deep sense of horror, grief, and moral reckoning over a life reduced to a price.

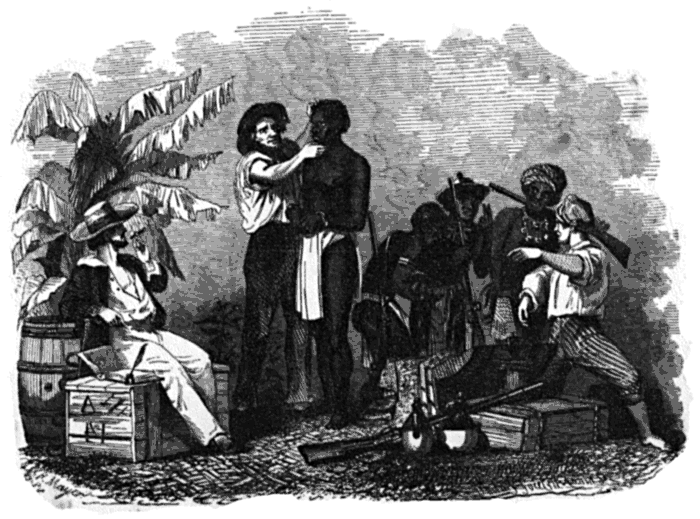

In the humid spring of 1827, on a small sugar plantation along the Mississippi River outside New Orleans, an enslaved girl known in records only as Celeste was sold for the price of two silver coins—a transaction so small it barely registered in the plantation ledger, yet one that would linger in local memory for generations.

According to surviving bills of sale and parish documents, Celeste was between twelve and fourteen years old, visibly ill, and considered “unfit for labor,” a phrase routinely used at the time to justify extreme price reductions for enslaved children and women.

The sale took place at dawn, overseen by plantation manager Étienne Roussel, who later testified that the owner wished to “remove a liability before summer sickness spread.”

Witnesses described Celeste as feverish, her clothing soaked with sweat, her breathing shallow as she was led from the slave quarters to the yard.

A neighboring enslaved woman later recalled hearing her whisper, “I won’t be here when the cane grows again,” a remark dismissed at the time as delirium.

The buyer, a small landholder named Auguste Lemoine, paid two coins—less than the cost of a chicken—and signed his name with a shaking hand, reportedly uneasy about the girl’s condition.

“She won’t last the week,” he allegedly muttered, according to an account recorded decades later by a local clerk.

Celeste never reached Lemoine’s property.

Parish burial records indicate that she died two days later in a storage shed on the edge of the plantation, having been left there while arrangements were made to transport her.

No physician was called.

No prayer was formally recorded.

Yet it was what Celeste reportedly said shortly before her death that transformed an otherwise routine act of cruelty into a story that refused to fade.

Several enslaved workers claimed that as night fell, she gathered her remaining strength and said, calmly and clearly, “You will remember me when the fields go quiet.

” Whether spoken in prophecy, pain, or resignation, those words spread quickly through the quarters.

Within months, the plantation faced a series of misfortunes that owners attributed to bad luck but workers quietly linked to Celeste’s death.

A late frost destroyed young cane.

Livestock fell ill.

An overseer was injured when a gallery railing collapsed.

By the following year, yields had dropped sharply, and Roussel resigned under pressure.

Letters from the owner to his brother in Baton Rouge reveal mounting anxiety.

“The people say the child cursed the land,” he wrote in October 1828.

“I do not believe such things, yet the silence in the fields unsettles me.”

Local folklore began to shape the narrative further.

Night watchmen claimed they heard coughing near the old shed.

Others said a small figure was seen at the edge of the cane rows during harvest, vanishing when approached.

While such stories were common in enslaved communities as expressions of grief and resistance, white residents also began to repeat them, reframing fear as superstition.

A visiting priest noted in his journal that parishioners spoke of “the sick girl sold for nothing, whose words linger like smoke.”

Modern historians caution against treating these accounts as literal hauntings, emphasizing instead what the story reveals about the moral landscape of slavery.

“Celeste’s so-called final words function as a collective memory,” said one New Orleans-based researcher in a recent lecture.

“They are a way the enslaved community named injustice when the law refused to.

” The two-coin sale appears in only one surviving ledger, but references to the girl appear indirectly in plantation correspondence for years afterward, often tied to unexplained unease or decline.

By the 1840s, the plantation was abandoned following repeated flooding and financial losses.

Today, little remains of the site beyond foundation stones and a historical marker installed in the late 20th century that mentions “unrecorded lives lost to slavery.

” Celeste’s name does not appear on it.

Still, her story endures, not because of the myths layered onto it, but because it exposes the brutal arithmetic of a system where a child’s life could be reduced to two coins—and where even in death, that child’s voice demanded to be remembered.

In the end, what haunted the plantation was not a ghost, but a truth its owners could never escape: some words, spoken at the edge of injustice, refuse to disappear.

News

New Zealand Wakes to Disaster as a Violent Landslide Rips Through Mount Maunganui, Burying Homes, Vehicles, and Shattering a Coastal Community

After days of relentless rain triggered a sudden landslide in Mount Maunganui, tons of mud and rock buried homes, vehicles,…

Japan’s Northern Stronghold Paralyzed as a Relentless Snowstorm Buries Sapporo Under Record-Breaking Ice and Silence

A fierce Siberian-driven winter storm slammed into Hokkaido, burying Sapporo under record snowfall, paralyzing transport and daily life, and leaving…

Ice Kingdom Descends on the Mid-South: A Crippling Winter Storm Freezes Mississippi and Tennessee, Leaving Cities Paralyzed and Communities on Edge

A brutal ice storm driven by Arctic cold colliding with moist Gulf air has paralyzed Tennessee and Mississippi, freezing roads,…

California’s $12 Billion Casino Empire Starts Cracking — Lawsuits, New Laws, and Cities on the Brink

California’s $12 billion gambling industry is unraveling as new laws and tribal lawsuits wipe out sweepstakes platforms, push card rooms…

California’s Cheese Empire Cracks: $870 Million Leprino Exit to Texas Leaves Workers, Farmers, and a Century-Old Legacy in Limbo

After more than a century in California, mozzarella giant Leprino Foods is closing two plants and moving $870 million in…

California’s Retail Shockwave: Walmart Prepares Mass Store Closures as Economic Pressures Collide

Walmart’s plan to shut down more than 250 California stores, driven by soaring labor and regulatory costs, is triggering job…

End of content

No more pages to load