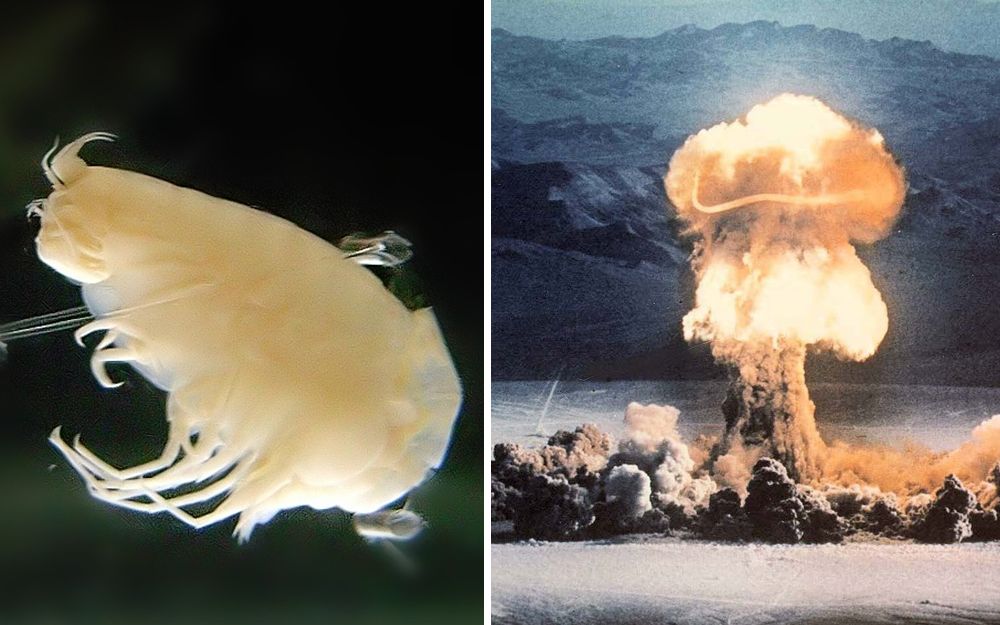

Scientists have confirmed that radioactive material is slowly leaking from the Cold War nuclear submarine K-278 Komsomolets on the North Atlantic seabed, a discovery that challenges decades of assumptions about ocean safety and raises deep unease about other forgotten nuclear wrecks still haunting the depths.

The deep ocean has long been treated as humanity’s final hiding place, a vast, dark expanse where the remnants of past conflicts could be left behind and forgotten.

That belief is now being dangerously challenged.

Scientists have confirmed that radioactive material is leaking from a Cold War–era nuclear submarine resting more than 5,000 feet below the surface of the North Atlantic, raising urgent questions about environmental safety, long-term accountability, and how many similar threats may still be hidden beneath the waves.

The submarine at the center of the alarm is the Soviet K-278 Komsomolets, which sank on April 7, 1989, after a catastrophic onboard fire during a routine patrol in international waters west of Norway’s Bear Island.

At the time, the disaster claimed the lives of 42 crew members and sent the vessel—along with its nuclear reactor and nuclear-armed torpedoes—to the seabed.

For decades, officials and scientists largely assumed that the extreme depth, low temperatures, and isolation of the site would effectively seal the wreck and prevent contamination.

Recent expeditions have proven that assumption wrong.

Using remotely operated vehicles and advanced sampling equipment, researchers have detected measurable levels of radioactive isotopes escaping from the submarine’s damaged hull.

According to scientists involved in the survey, traces of cesium and other radioactive particles were found in sediments and water samples taken near the wreck.

“There is no single dramatic failure,” one researcher explained during a briefing.

“It’s a slow, continuous seepage—the most dangerous kind because it’s easy to ignore.”

The location of the wreck has amplified concern.

The Komsomolets lies near ocean currents connected to some of the North Atlantic’s most productive fishing regions.

While experts emphasize that radiation levels detected so far do not pose an immediate risk to human health, they warn that long-term exposure and bioaccumulation in marine life remain poorly understood.

“Radiation doesn’t disappear,” a marine physicist noted.

“It spreads, it settles, and it works its way into ecosystems over time.”

The submarine itself was never an ordinary vessel.

Built with a titanium hull, Komsomolets was designed to dive deeper than any previous submarine, operating at depths that pushed the limits of Cold War engineering.

It was a technological statement as much as a military asset, intended to evade detection and survive extreme pressure.

That same design, however, now complicates efforts to assess and contain the damage, as corrosion behaves differently at such depths and on specialized materials.

The sinking in 1989 was sudden and chaotic.

After a fire broke out in the aft compartment, critical systems failed one by one.

The crew fought for hours to save the submarine, even managing to surface briefly before it finally slipped beneath the waves.

When it sank, its nuclear reactor was shut down, but two nuclear-tipped torpedoes remained onboard—an unsettling fact that has lingered quietly in official records ever since.

What alarms scientists now is that Komsomolets may not be an isolated case.

During the Cold War, multiple nuclear submarines from both the Soviet Union and the United States were lost at sea, along with nuclear weapons deliberately scuttled or accidentally dropped in various parts of the world’s oceans.

Many of these sites have never been thoroughly monitored.

“We’re only just beginning to understand what decades underwater actually do to these materials,” said one oceanographer involved in nuclear-wreck assessments.

“The ocean is not a perfect vault.”

The confirmation of leakage has reignited debate over responsibility and transparency.

Russia has previously conducted limited sealing operations on the wreck, but no comprehensive containment has been attempted in recent years.

International maritime law offers little clarity on who is obligated to manage aging nuclear hazards in international waters, especially when the vessels belong to a state that no longer exists in the form it did when the accident occurred.

Environmental groups argue that the discovery should serve as a wake-up call.

“This is a legacy problem,” one advocate said.

“We created these weapons, we lost them, and now the planet is paying the interest.

” Scientists echo that sentiment, stressing that continued monitoring—and potentially costly intervention—may be the only way to prevent a slow-motion environmental crisis.

There is no explosion looming, no dramatic countdown clock.

The danger posed by Komsomolets is quieter, unfolding molecule by molecule in the dark.

Yet that silence may be precisely what makes it so unsettling.

As new data emerges, one conclusion is becoming harder to ignore: the Cold War did not end everywhere, and on the ocean floor, its consequences are still leaking into the present.

News

New Zealand Wakes to Disaster as a Violent Landslide Rips Through Mount Maunganui, Burying Homes, Vehicles, and Shattering a Coastal Community

After days of relentless rain triggered a sudden landslide in Mount Maunganui, tons of mud and rock buried homes, vehicles,…

Japan’s Northern Stronghold Paralyzed as a Relentless Snowstorm Buries Sapporo Under Record-Breaking Ice and Silence

A fierce Siberian-driven winter storm slammed into Hokkaido, burying Sapporo under record snowfall, paralyzing transport and daily life, and leaving…

Ice Kingdom Descends on the Mid-South: A Crippling Winter Storm Freezes Mississippi and Tennessee, Leaving Cities Paralyzed and Communities on Edge

A brutal ice storm driven by Arctic cold colliding with moist Gulf air has paralyzed Tennessee and Mississippi, freezing roads,…

California’s $12 Billion Casino Empire Starts Cracking — Lawsuits, New Laws, and Cities on the Brink

California’s $12 billion gambling industry is unraveling as new laws and tribal lawsuits wipe out sweepstakes platforms, push card rooms…

California’s Cheese Empire Cracks: $870 Million Leprino Exit to Texas Leaves Workers, Farmers, and a Century-Old Legacy in Limbo

After more than a century in California, mozzarella giant Leprino Foods is closing two plants and moving $870 million in…

California’s Retail Shockwave: Walmart Prepares Mass Store Closures as Economic Pressures Collide

Walmart’s plan to shut down more than 250 California stores, driven by soaring labor and regulatory costs, is triggering job…

End of content

No more pages to load