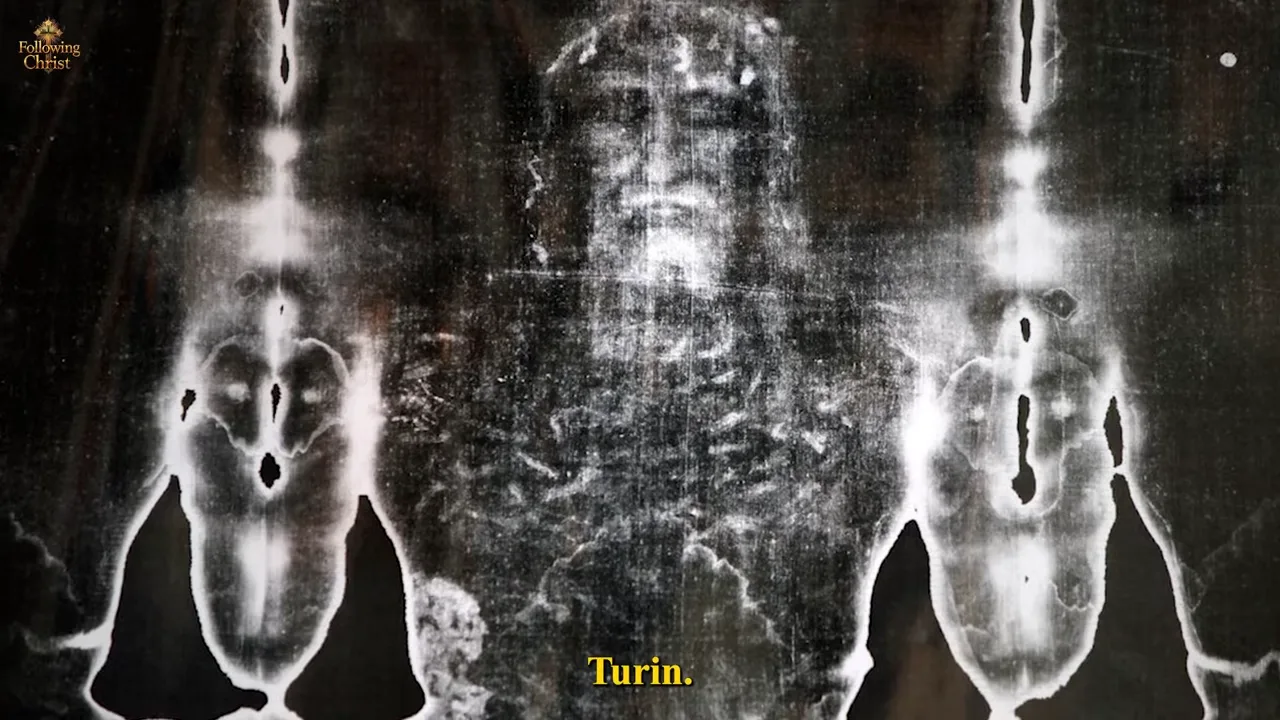

The Shroud of Turin, a centuries-old linen cloth, is one of the most mysterious and controversial relics in history.

Believed by many to be the actual burial shroud of Jesus of Nazareth, it holds an image that has intrigued scientists, theologians, and skeptics alike.

But what makes this cloth so extraordinary?

It’s not just the religious implications, but the baffling scientific properties of the image it bears.

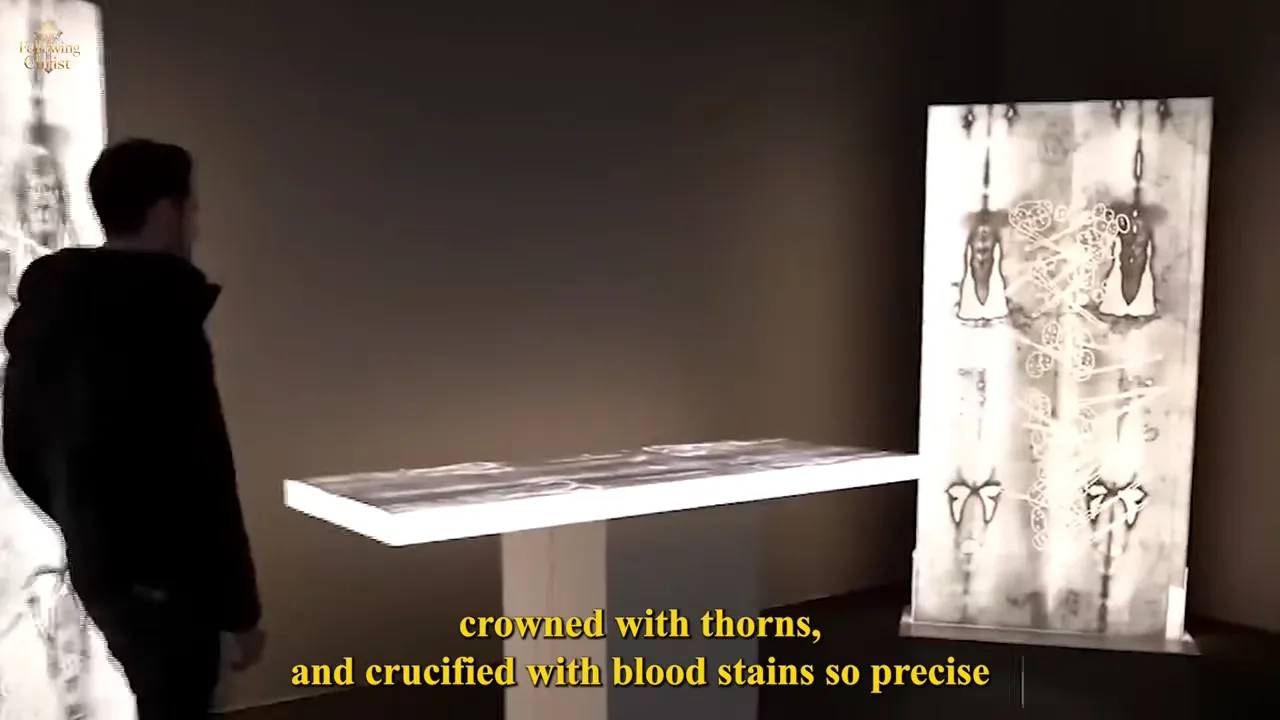

Imagine discovering a strange image on an ancient piece of cloth that shows in full detail the body of a man who has been beaten, crowned with thorns, and crucified.

The blood stains are so precise that forensic doctors can read the entire history of the man’s suffering from them.

Even more astonishing, the image behaves like a photographic negative that shows features like an X-ray, and even more perplexing, it has properties similar to a hologram—a three-dimensional image.

Yet, this image appeared centuries before photography, X-rays, and holograms were invented.

This raises a deeply compelling question: How did this image form on the cloth?

If it is simply a painting, a hoax, or a random stain, then science should be able to demonstrate that.

But what if the very act of resurrection left a physical imprint on the cloth?

If this is the case, we are standing before a strange kind of evidence—something that has never occurred a second time in history.

This article will explore the main arguments from imaging, science, forensic medicine, and theology, all converging on one mind-boggling conclusion: The image on the Shroud of Turin is not a painting.

It is not the product of ancient people using primitive tools and techniques.

Instead, the image is the result of a phenomenon of light and energy emitted from the body of a man who died and rose again.

To understand how an image can be printed onto a surface without using brush or ink, let’s consider a modern historical event.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

After the explosion, people discovered human shadows etched onto walls and sidewalks, outlines of those who had been standing there, apparently printed by the light of the blast.

At first glance, one might think someone had painted these silhouettes on the walls.

But the reality is far more intriguing.

The human body blocked the blinding intense light of the explosion, and the surrounding surfaces—concrete, stone, and walls—were bleached by the light.

If the areas shielded by the body retained their original color, the result was a dark shadow left behind on the surface.

It wasn’t the shadow being burned into the wall.

Instead, it was the surrounding areas that were bleached by the light, creating an image through a photochemical and thermal process.

No direct contact was involved between the body and the wall, and the image was created purely by light and heat.

This process of light creating an image without ink, brush, or carving is the first analogy we can use to understand the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud’s image is not identical to the Hiroshima shadows, but there are key similarities.

There is an extremely powerful light source.

The body or object is very close to the recording surface—the cloth.

Light, especially ultraviolet (UV) light, interacts with the surface of the cloth, changing its chemical structure and color.

The shades of light and dark in the image depend on the distance between the body and the surface.

In Hiroshima, light and heat created images without human contact.

In the case of the Shroud of Turin, we see a similar, but far more complex, process.

When comparing the Hiroshima shadows and the Shroud of Turin, we can summarize six key similarities and one crucial difference:

-

The object (body) is close to the recording surface.

In Hiroshima, people were standing or sitting close to the wall or pavement, creating shadows.

In Turin, the body lies above and below the linen cloth.

The image is darker where it is closer.

In Hiroshima, parts of the body closer to the wall appeared darker.

On the Shroud, parts of the body closest to the cloth—like the face and chest—produced the sharpest, clearest images.

The image fades as distance increases.

In Hiroshima, parts of the body farther from the wall produced fainter shadows.

On the Shroud, the image becomes faint and eventually disappears along the sides, where the cloth is farther from the body.

Ultraviolet (UV) light is involved in image formation.

In Hiroshima, the nuclear explosion produced a broad spectrum of radiation, including UV, which altered surfaces.

In the case of the Shroud, all data points to UVB radiation as the most reasonable candidate to explain the rapid discoloration on the surface layer of the linen fibers.

The surface acts like a film plate.

In Hiroshima, the walls and sidewalks acted as film plates, recording the shadows.

On the Shroud, the linen cloth acts as a double-sided film plate, with one side in front of the body and one behind it.

The closer, the sharper.

In both cases, resolution is highest where the object is closest to the recording surface.

But here’s the key difference that makes the Shroud of Turin truly unique:

In Hiroshima, the shadows do not encode detailed information about distance.

You cannot look at them and determine how many centimeters the person was from the wall.

With the Shroud of Turin, the degree of shading across the cloth encodes the distance between the body and the cloth so precisely that when the image is run through a brightness analyzer (VP8 image analyzer), it produces an accurate 3D model of the body, down to the millimeter.

This kind of precision has never been observed in any painting, photograph, X-ray, hologram, or any other human artifact.

Moreover, when magnifying a thread from the Shroud of Turin 10,000 times, researchers discovered something astonishing.

Only one out of every 200 fibers was discolored, and the discoloration only affected the outermost surface of the fibers.

There was no trace of ink, paint, dye, or any pigment—organic or inorganic—on the surface.

This means no one could have painted the image in the way we think of painting today.

No ancient technique and certainly no modern methods could affect fibers in such a precise and uniform way across a cloth over 4 meters long.

This leads to a crucial scientific conclusion: The image was not created by adding paint, ink, or dye.

It is the result of a highly localized process of rapid aging, dehydration, and oxidation on the linen’s surface.

So, what could cause rapid aging, dehydration, and a sepia brown color change?

The best answer the research group found after 500,000 hours of study is high-intensity UVB radiation, emitted in a laser-like form.

The light that caused the discoloration was highly concentrated, single-wavelength light—like a laser.

Interestingly, this phenomenon has a parallel in everyday life: tanning.

UV light accelerates aging, causes dehydration, and triggers oxidative reactions that turn the skin brown.

However, with normal sunlight, UV rays are scattered in all directions, hitting everything exposed.

But with the Shroud of Turin, the light behaved much more like a laser—highly focused and striking only extremely small, shallow points on the linen fibers.

This rules out ordinary sunlight and primitive photography methods from the Middle Ages.

The closest reproductions of the Shroud’s image have only succeeded when using an argon fluoride laser under controlled conditions.

But one big question remains: Where did such laser-like light come from in the case of the Shroud?

This brings us to a little-known scientific fact: Human DNA emits photons.

Modern research shows that every second DNA in living cells emits around 100,000 to 1,000,000 photons of extremely faint UV light.

This light is invisible to the naked eye but can be measured with sensitive instruments.

If this process were greatly amplified through some kind of electric field or resonant effect, then the DNA in a human body could become a source of laser-like UVB radiation.

In that scenario, each cell, each DNA segment could emit light at very precise frequencies, causing the linen fibers in direct proximity to undergo rapid aging, dehydration, and color change.

In other words, the body itself is the light source.

That light leaves the body, passes through space, strikes the cloth, and encodes distance in the number of fibers that are discolored.

This leads to a strong conclusion: The cloth did not just change color randomly.

No one simply shone a lamp onto the linen.

It was the body inside the cloth that emitted the light.

And that’s why the image carries 3D information about that body—negative, X-ray, hologram—all in one.

The Shroud of Turin remains one of the most perplexing and compelling mysteries in the world.

Whether or not it is the actual burial cloth of Jesus, it certainly seems to contain evidence of something extraordinary.

News

FBI & ICE Raid Michigan Port — 8,500 Pounds of Drugs & Millions SEIZED

FBI & ICE Raid Michigan Port — 8,500 Pounds of Drugs & Millions SEIZED In the early hours of the…

FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis — 3,000 ARRESTED, 2,000 AGENTS & The GUARD’S Defiance

FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis — 3,000 ARRESTED, 2,000 AGENTS & The GUARD’S Defiance In the early morning hours of…

“YOU DEFAMED ME ON LIVE TV — NOW PAY THE PRICE!” — Ronnie Dunn Drops a $50 MILLION Legal Bomb on The View and Sunny Hostin After Explosive On-Air Ambush

“YOU DEFAMED ME ON LIVE TV — NOW PAY THE PRICE!” — Ronnie Dunn Drops a $50 MILLION Legal Bomb…

ICE & FBI Raid Chicago — Massive Cartel Alliance & Fentanyl Empire Exposed

ICE & FBI Raid Chicago — Massive Cartel Alliance & Fentanyl Empire Exposed In the early hours of a seemingly…

ICE & FBI STORM Minneapolis — $4.7 Million, 23 Cocaine Bricks & Somali Senator EXPOSED

ICE & FBI STORM Minneapolis — $4.7 Million, 23 Cocaine Bricks & Somali Senator EXPOSED In the early hours of…

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Cartel – Somali-Born Senator & 19B Fraud Exposed

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Cartel – Somali-Born Senator & 19B Fraud Exposed In the early hours of a frigid…

End of content

No more pages to load