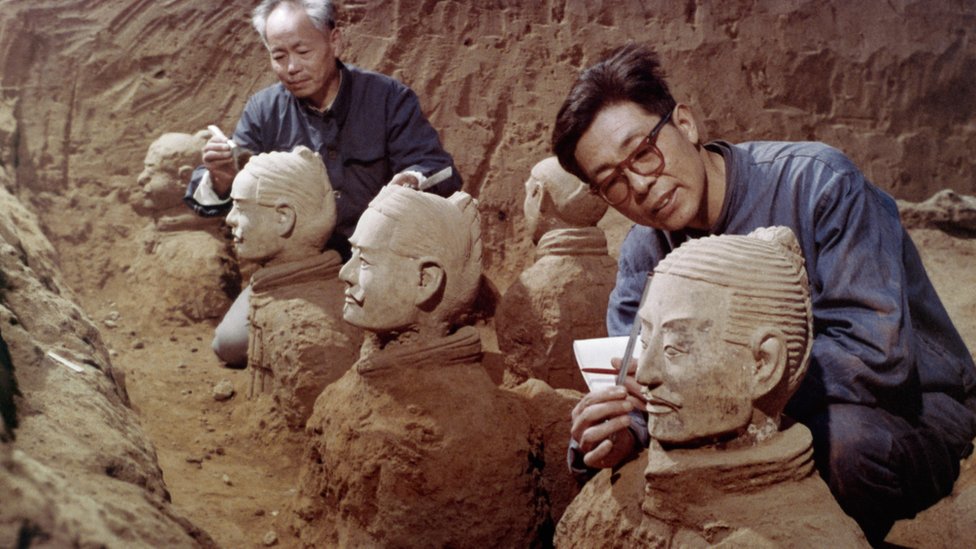

When the silent clay legions of Qin Shi Huang — China’s First Emperor — were first brought to light in 1974, they astonished the world. Over two thousand years after their burial, the thousands of life-sized figures of the Terracotta Army (兵马俑) still guard his tomb in the shadow of Mount Li in Shaanxi province.

But then, in 2025, something remarkable happened: advanced AI-driven scanning and reconstruction techniques were applied in a major digitization and analytical push. The results? They may force historians to rethink major aspects of ancient China, the reach of Qin imperial power, and the very meaning of immortality in that era.

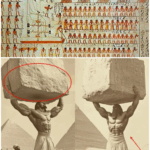

The Terracotta Army was commissioned by Qin Shi Huang in the late 3rd century BC to accompany him in death and protect his rule beyond the grave. Excavated in 1974 by chance, these figures were buried in massive pits around the emperor’s mausoleum and have since become one of archaeology’s greatest treasures.

The statues are astounding: lifelike, varied in posture and facial expression, detailed in attire and armament. They reflect immense craftsmanship, imperial power and the belief in the need for protective forces in the afterlife.

In recent years, Chinese heritage institutions and research teams have begun applying new technologies to the site: 3D scanning, point-cloud analysis, machine-learning segmentation of fragments, and AI-based reconstruction of fragmented statues.

For example, in 2022 researchers used 3D point clouds and facial-feature analysis to show that the sculpted faces of the warriors “highly resemble those of contemporary Chinese people” — suggesting the figures may have been based on real individuals. Moreover, scanning robots now create ultra-high-resolution models of individual statues in minutes.

The key turning point: in 2025, the digitization effort matured into full-scale AI-driven analysis of the entire army, applying deep learning, pattern recognition, and large-scale comparative modelling to explore hidden details beneath the surface of the clay.

Diversity of Faces = Real People as Models

The AI found subtle facial-landmark variations across thousands of statues which cluster into distinct groups. One analysis concluded that the warriors were not generic “idealised” figures, but likely modelled on actual people from the Qin empire — perhaps officers, regional recruits, or foreign contingents.

Implication: The Qin state may have drawn on a wider demographic base than previously thought — regional levies, conscripts, or even captives may have been included. The army in clay was a mirror of the real imperial army in diversity, not just mythic unity.

2. Hidden Armour & Weapon-Marks Under Surface Scans

Using multi-spectral imaging and AI segmentation, researchers detected near-invisible traces on many figures of pigment patterns, armour binding, and weapon-slits that had eroded away. These hidden details suggest each warrior’s gear was more individualized than earlier believed.

Implication: The assumption that the Terracotta Army was a mass-produced uniform tribute is challenged. Instead, it hints at a highly organised and finely differentiated martial force. The scale of the Qin military machine may have been far more sophisticated.

Burial Logistics and Workshop Networks Re-Mapped

The AI analysis of manufacturing marks and clay composition across workshops revealed that production of the statues was not solely local but drawn from at least three distinct clay-sourcing zones. This suggests a vast logistical network funneling raw materials and labour across distances.

Implication: Qin Shi Huang’s project was not just monumental in scale — it was a national enterprise in the true sense, involving regional mobilisation, large-scale coordination and state-level industrial capability.

Re-imagining the Emperor’s Vision of Immortality

If the Terracotta Army reflects actual people, and if the equipment and production networks were this complex, then perhaps the emperor’s plan for immortality was more than symbolic. The project may have been intended as a functional “mirror-force” of his earthly army, not simply a decorative afterlife guard.

Implication: The ideology behind the tomb changes: it becomes not only an expression of tomb-wealth, but a deliberate operational extension of imperial power beyond death. The boundary between life and after-life blurs in a profound imperial fantasy.

What This Means for Ancient China Studies

Reassessing Qin State Capacity: The findings suggest the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) had administrative, military and industrial capabilities previously believed to belong only to later ages.

Rethinking Margins and Inclusion: If the statue-models were drawn from across the empire — perhaps even non-Han groups — our picture of the Qin realm’s integration and mobilization shifts.

New Models of Funerary Art: Instead of purely symbolic tomb art, the Terracotta Army may be a functional mirror of power, pushing scholars to ask: how did rulers visualise rule in death?

Technology as Historical Agent: The very fact that AI is rewriting narratives means historians must now treat digital-heritage methods as part of the story, not just tools.

Terracotta Army, Qin Shi Huang, AI scanning archaeology, ancient China, 3D scanning cultural heritage, digital humanities China, Qin dynasty military, terracotta warriors discovery, Chinese imperial tombs, afterlife immortality China.

For more than two thousand years, the Terracotta Army has stood in silent vigil over the tomb of China’s first emperor. Now, thanks to AI-driven scanning and analysis in 2025, those silent clay legions may speak louder than ever — telling us not just about art and ritual, but about military might, imperial ambition, identity and the afterlife. The empire that unified China two millennia ago may have reached farther, and deeper, than we ever imagined.

News

🐻 10 Insanely Rich UFC Fighters Who Live Like Your Neighbor Next Door

You’d expect UFC’s wealthiest fighters to be living like Hollywood stars — luxury cars, mansions, designer clothes, and private jets….

🐻 Nate Diaz Breaks His Silence — And Fans Are Heartbroken

UFC legend Nate Diaz has finally spoken out — and the MMA world is reeling. Known for his raw honesty,…

🐻 Islam Makhachev Destroys Topuria & Pimblett In Brutal Interview: “They’re Not Real Fighters!”

Islam Makhachev has once again reminded the MMA world why he’s not just the UFC lightweight champion, but also one…

🐻 Why does Ronda Rousey dislike Joe Rogan? How their relationship changed after KO defeats

Ronda Rousey’s latest jab at Joe Rogan has made fans curious about their one-sided feud. ‘Rowdy’ recently branded the UFC’s…

🐻 Dana White breaks his silence following UFC Vegas 110 fight-fixing scandal… ‘It doesn’t look good’

UFC boss Dana White has broken his silence following the fight-fixing scandal that the promotion has been embroiled in over…

🐻 Manny Pacquiao explains why he would box Conor McGregor but reject Khabib Nurmagomedov

Manny Pacquiao is open to a crossover fight with MMA’s biggest star. Pacquiao made his boxing comeback in 2025, challenging…

End of content

No more pages to load