Uncovers a Lunar Mystery That Could Change Space Exploration Forever

For decades, the Moon appeared settled in the human imagination. A silent companion. Mapped, measured, photographed, walked upon.

Its mysteries, many believed, had already been reduced to data points and dusty samples locked away in laboratories.

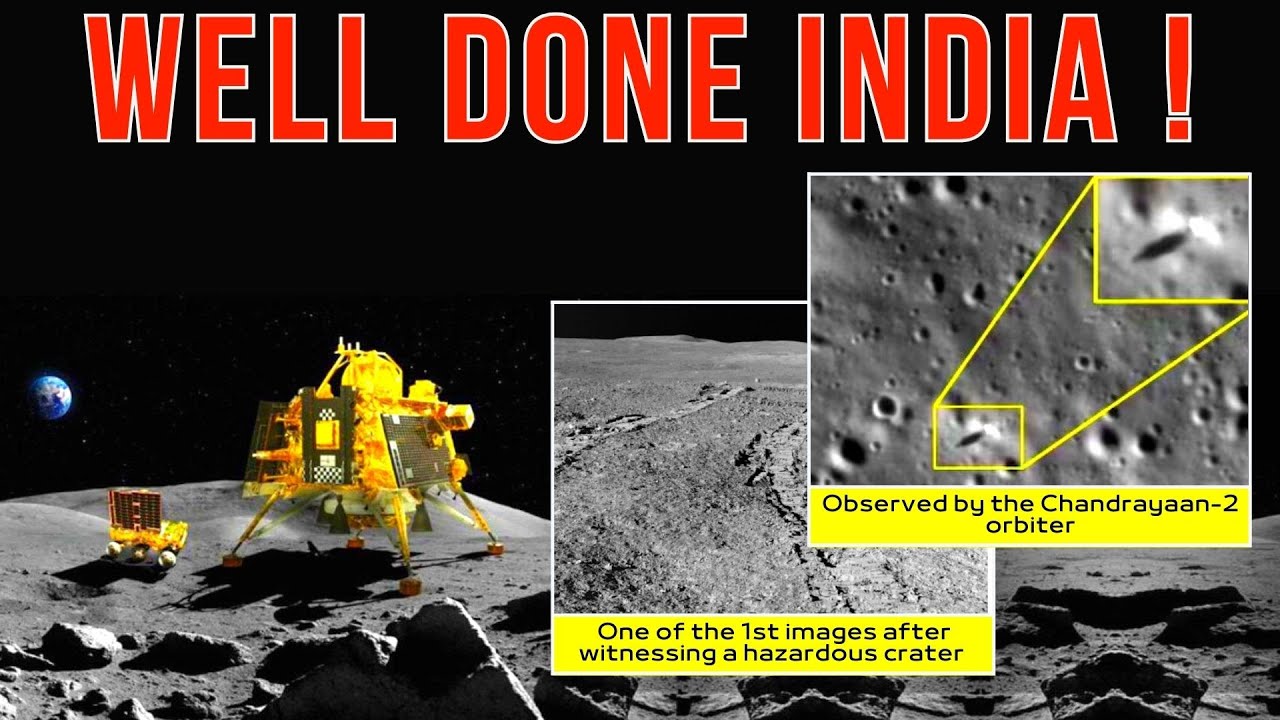

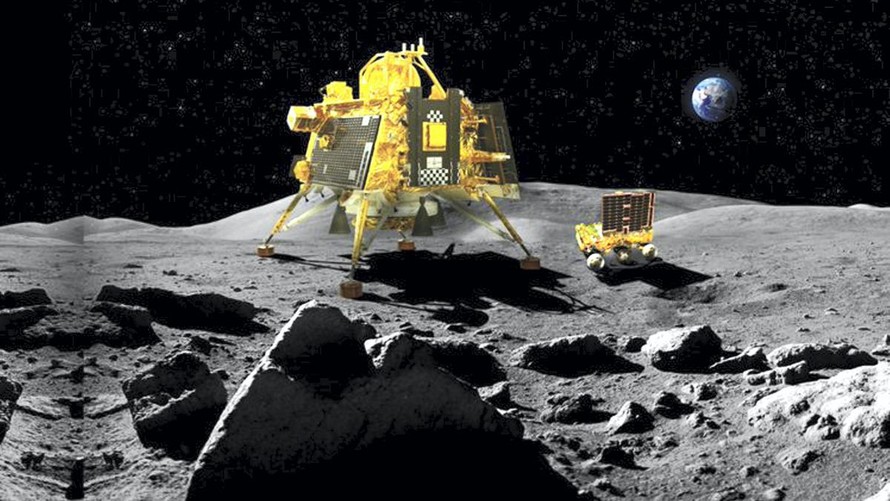

But that illusion fractured quietly, almost politely, when India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission touched down near the Moon’s south pole.

No explosion. No dramatic broadcast interruption.

Just a stream of numbers, temperatures, vibrations, and signals that, when pieced together, began to suggest something far more unsettling than anyone had anticipated.

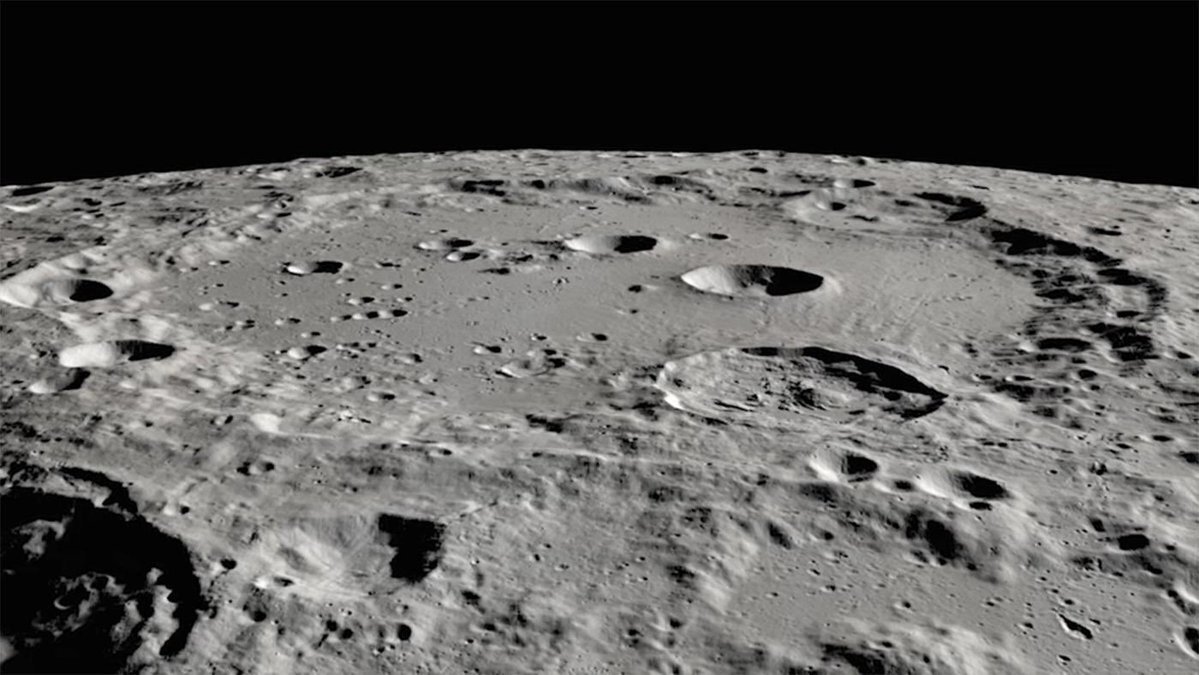

The south pole of the Moon has always been different.

Unlike the familiar equatorial regions visited by Apollo astronauts, this terrain lives in a permanent dance between light and darkness.

Some craters have not seen sunlight for billions of years.

Inside them, temperatures plunge lower than any naturally occurring place on Earth.

Scientists long suspected these frozen shadows might hide water ice, trapped like a time capsule from the early solar system.

Chandrayaan-3 was designed, in part, to confirm that theory.

What it returned instead has ignited a storm of debate, caution, and uneasy fascination.

Almost immediately after the landing, mission scientists noted anomalies.

The lunar soil behaved differently than expected.

Thermal readings fluctuated sharply over short distances, as if the surface itself were layered with hidden contrasts.

In certain shadowed regions, instruments recorded chemical signatures that didn’t neatly align with existing lunar models.

Official statements were careful, measured, restrained.

But behind closed doors, questions multiplied faster than answers.

At the heart of the controversy lies the Moon’s regolith, the fine, dusty blanket covering its surface.

Chandrayaan-3’s sensors revealed that beneath this powdery exterior, the soil structure changes abruptly near the south pole.

Some layers appeared unusually compact, others strangely reactive to temperature shifts.

When heated even slightly, parts of the regolith responded in ways that surprised researchers.

It was as if the Moon, long assumed inert, was quietly signaling that it is not as passive as humanity once believed.

Then there was the ice.

Yes, evidence strongly suggests water ice exists in the permanently shadowed craters.

But not all ice is the same.

Chandrayaan-3’s data hints that this ice may be mixed with other frozen compounds, possibly delivered by ancient comets or formed through chemical reactions unique to extreme cold and radiation exposure.

Some scientists speculate that these mixtures could become unstable if disturbed, especially by drilling, mining, or sustained human presence.

This is where the narrative begins to shift from discovery to dilemma. The Moon’s south pole is no longer just a scientific curiosity.

It is the focal point of future ambitions. NASA, China, and other space agencies have openly discussed building lunar bases in this region, precisely because of its suspected water resources.

Water means oxygen. It means fuel. It means permanence. But Chandrayaan-3’s findings raise an uncomfortable possibility: accessing these resources may come at a cost no one has fully calculated.

One concern gaining quiet traction involves trapped gases.

In the Moon’s airless environment, volatile substances can remain locked beneath the surface for eons. If released suddenly, they could alter local conditions, interfere with equipment, or create hazards for astronauts.

Some researchers draw parallels to permafrost regions on Earth, where thawing ground has unleashed unexpected geological and chemical reactions.

The difference is that on the Moon, there is no atmosphere to buffer or disperse what might escape.

Another debate centers on the Moon’s ancient history.

The south pole may preserve materials dating back to the earliest days of the solar system, untouched by sunlight or geological recycling.

This makes it invaluable to science.

Yet that same pristine state means it is fragile.

Even a single landing, repeated over time, could permanently alter environments that have remained unchanged for billions of years.

Chandrayaan-3’s success has, paradoxically, highlighted how little margin for error exists.

Publicly, space agencies continue to emphasize optimism.

The language remains hopeful, forward-looking, inspirational.

Privately, caution is creeping in.

Some scientists argue that humanity is standing at the edge of a lunar threshold, one that demands restraint rather than acceleration.

Others counter that fear has always accompanied progress, and that the Moon is no exception.

The disagreement is not merely technical; it is philosophical.

There is also a quieter, more speculative undercurrent to the discussion.

A handful of researchers have noted patterns in the data that defy easy explanation.

Minor electromagnetic fluctuations.

Temperature gradients that don’t correspond neatly to sunlight exposure.

These observations are not being framed as evidence of anything extraordinary, but they linger, unresolved, in technical briefings and internal reports.

Enough to provoke curiosity. Not enough to draw conclusions.

What unsettles many is not the presence of a single alarming discovery, but the accumulation of small, unexpected details.

Each anomaly alone could be explained away.

Together, they form a picture that feels incomplete, as though Chandrayaan-3 has only brushed the surface of a deeper story.

A story written in ice, dust, shadow, and time.

The Moon has always been a mirror for human ambition. Once, it symbolized conquest. Later, cooperation.

Now, it represents sustainability beyond Earth.

But Chandrayaan-3 suggests that the Moon may not simply accept these projections.

It has its own rules, its own conditions, its own buried history. And the south pole, in particular, appears to be where those rules are most unforgiving.

As nations race to stake their presence in cislunar space, the question is no longer whether humans can return to the Moon.

That seems inevitable. The question is whether they are prepared for what the Moon’s most mysterious region might demand in return.

Technology can adapt. Missions can be redesigned. But humility is harder to engineer.

India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission has been celebrated as a triumph of precision and perseverance, and rightly so.

Yet its greatest contribution may not be technological at all.

It has forced the world to reconsider assumptions that had quietly hardened into certainty.

The Moon is not fully known. Not yet. Perhaps not ever.

In the coming months and years, more data will be released, more interpretations offered, more confident statements made.

Some of today’s concerns may fade under scrutiny. Others may sharpen into warnings.

For now, the south pole remains what it has always been: a place of darkness, cold, and secrets. Only now, humanity knows those secrets may not want to stay buried.

And as spacecraft plan their descent paths and astronauts train for future missions, a single thought lingers unspoken but persistent: when we finally dig into the Moon’s darkest ground, will it give us what we seek — or reveal something we were never meant to disturb?

News

Lil Baby’s “Undeserving” Comment Sparks Firestorm as Jaw Morant Pushes Back Against Viral Narratives

When One Comment Goes Viral: How Lil Baby and Jaw Morant Became the Center of an Online Culture War The…

21 Savage’s Call for Peace Reignites Questions Around Young Thug and Gunna’s Fractured Bond

21 Savage’s Words Force the Young Thug–Gunna Tension Into the Spotlight Again In a genre built on loyalty, silence, and…

Wiz Khalifa and Romania: The Unclear Case Behind the Rumored 9-Month Sentence

From Global Icon to Legal Uncertainty: Why Wiz Khalifa’s Name Is Dominating Headlines In recent days, the name Wiz Khalifa…

Drake’s Rolls-Royce Christmas Gift to BenDaDonnn Sparks Praise, Backlash, and Unanswered Questions

Why Drake’s Christmas Surprise for BenDaDonnn Has the Internet Divided In the final days leading up to Christmas, when social…

Chris Brown Surpasses Michael Jackson in U.S. Sales, Igniting a Cultural Firestorm

A New King or a Misleading Crown? Chris Brown’s Record Sparks Global Debate The comparison was inevitable, yet few expected…

Lil Wayne’s Unexpected Performance Ignites Debate Over Hip-Hop’s Voice and Future

A Moment That Stopped the Industry: Why Lil Wayne’s Latest Appearance Still Divides Audiences For weeks, the industry moved as…

End of content

No more pages to load