The Last Path of Daniel Mercer

In the fall of 1999, when the northern wetlands were beginning to rot under the weight of the coming winter, Daniel Mercer locked his cabin door, slung his rifle over his shoulder, and whistled for his retriever, Boone. He was fifty-one, steady as the tide, and had hunted the marshlands longer than most men had been alive. Locals joked that Daniel knew the wetlands better than he knew any human being. Some said the land had chosen him; others whispered it was the other way around.

That morning, the fog didn’t lift. It thickened, weaving through the reeds until the path ahead disappeared into a sheet of white. Daniel didn’t seem bothered. He had walked that trail a hundred times, boots sinking into the peat, rifle steady across his back. Boone followed closely, tail low, ears high. Something in the air felt off, but Daniel pressed on.

He was last seen by a pair of hikers heading out before sunrise. They recalled his calm nod, the dog at his heel, and the quiet way he seemed to disappear between the cattails. They didn’t think much of it. People like Daniel moved through nature as if it parted for them.

By late afternoon, Boone returned alone.

The dog scratched at the cabin door until a neighbor heard the noise. Boone was soaked in black swamp water, shaking, whining, his paws sliced by something sharp. But the worst part wasn’t what they saw. It was what they didn’t.

There was no sign of Daniel.

The search was immediate. Dozens of volunteers trudged through the wetlands, calling his name. Helicopters skimmed low, blades slicing through fog. Cadaver dogs were brought in, though some refused to walk certain stretches of the marsh, whining and snapping at handlers. The land felt hostile, ancient, hungry in a way no one could name.

Nothing turned up. No rifle. No gear. No boot prints. Daniel’s truck sat untouched at the trailhead, keys still in the glove compartment. His thermos, still warm, rested in the cup holder.

By the third week, people began to murmur. Some said Daniel had walked into the swamp on purpose. Others said he’d stumbled into a sinkhole, swallowed by centuries of mud. A few whispered that Boone came back too quickly, as if the dog had been running from something.

The official case file closed with the usual line: no sufficient evidence to determine cause of disappearance.

The unofficial story lingered like the fog that never quite cleared.

For twenty-five years, the wetlands held their silence.

In 2024, the region experienced the driest season on record. The marsh shrank, revealing patches of earth that hadn’t seen daylight since before the Civil War. Locals wandered through the cracked basin, gathering old bottles, lost tools, bits of rusted metal. It was treasure hunting for people who’d never left the county.

One of them, a retired lineman named Curtis Hale, spotted something halfway buried in the mud beside a dead cypress. At first he thought it was driftwood. Then he saw the shape of the barrel.

A bolt-action rifle, eaten by rust, warped by decades of rot but unmistakable. The serial number matched Daniel Mercer’s. The same rifle he carried on the day he vanished.

Curtis reported it, and within hours the marsh filled with police tape. Investigators combed the area, though most of the ground was still too unstable to dig deeper. People gathered at the edges, whispering like the old days.

If the marsh had finally given something back, they thought, maybe it would give more.

The rifle wasn’t the only thing the drought revealed.

A week later, a volunteer scout named Lily Granger found an old hunter’s satchel lodged beneath a fallen log. It was torn open, half-decomposed, but inside were things that made investigators pause: a compass bent backward, as if crushed from within; a metal flask dented in a strange pattern; and a strip of flannel fabric, faded but still showing red and gray plaid.

Daniel had been wearing a flannel that day.

But the strangest item wasn’t the fabric or the bent compass.

It was the notebook.

Thin, waterlogged, pages stuck together like layers of old skin. On the first page, smeared in mud, was Daniel’s handwriting: “Found the markers again. Not where they used to be.”

Markers. No one knew what he meant. The wetlands had no mapped markers besides the usual game trails. But in later entries, written days before his disappearance, Daniel mentioned them several times:

“Saw one near the old stump. Boone growled.”

“Second marker deeper in the fog. Something moved behind it.”

“Stopped sleeping. The marsh feels wrong.”

The last entry was barely legible. “Not alone out here.”

When the notebook was announced publicly, theories exploded.

Some locals insisted Daniel had stumbled across illegal poachers. Others assumed he had found evidence of something criminal buried in the marsh. The more imaginative believed there were older things beneath the surface, relics of the tribes that once lived on the land, meant to be left alone.

The search area expanded. Drones mapped the marsh from above. Archaeologists joined the effort, claiming the markers Daniel wrote about could be boundary stones or old burial sites. But nothing concrete surfaced.

That was when federal agents arrived.

Not publicly. Not officially. But people saw men in unmarked trucks, carrying equipment no one recognized, setting up scanners and digging without explanation.

Something had changed.

Two months after the rifle was discovered, Boone’s old collar was found.

It was curled in the mud beside a narrow creek bed, metal tag still faintly readable. Boone had lived another seven years after Daniel disappeared, dying peacefully on the porch of Daniel’s nephew. No one understood how the collar had ended up back in the marsh.

Investigators brushed it off as coincidence. But locals didn’t buy it.

Boone had returned home without his collar.

Which meant Daniel had removed it. Or someone else had.

Rumors turned violent. People claimed the wetlands were shifting, swallowing things that didn’t belong and spitting out things that did. Hunters swore they heard voices at dusk. A pair of teenagers posted a shaky video online, claiming they saw a figure standing waist-deep in the fog. It went viral, though no one could tell if it was real.

And then came the final twist.

During a late-season excavation, a team uncovered a buried wooden post carved with markings—symbols that didn’t match any known tribal language. The post had been driven deep into the mud with deliberate force.

At the base of the post was a scrap of cloth.

Red and gray plaid.

DNA testing confirmed it. The fabric belonged to Daniel’s shirt.

But there was no trace of his body. No bones. Nothing human.

What chilled investigators wasn’t what they found.

It was where the cloth was buried.

Two miles from where the rifle surfaced.

One mile from the satchel.

Half a mile from where Boone returned to the trailhead.

Daniel had been moving.

Or something had been moving him.

Reporters tried to turn it into a ghost story. Scientists leaned toward environmental explanations. Anthropologists argued for cultural misinterpretation. But no one had a theory that explained everything: the shifting locations, the notebook entries, the collar that shouldn’t have been there.

After months of study, the wetlands refilled with winter rain. The marsh swallowed the excavation pits, the markers, the wooden post, the last exposed remnants of what had been found.

By spring, it all vanished again.

Today, the official word is simple:

Daniel Mercer vanished in 1999. Evidence found in 2024 was inconclusive.

That’s all the state will admit.

But locals still talk about it.

They say the marsh gave back just enough to remind everyone that it remembers.

They say it took Daniel because he saw something he shouldn’t have.

They say the land keeps its own stories, and only tells fragments when it wants to.

Whether he died in the wetlands, or kept moving long after he should have fallen, no one knows.

What remains is a rifle. A notebook. A collar. A scrap of cloth.

And a trail that leads into fog that no one has dared follow since.

News

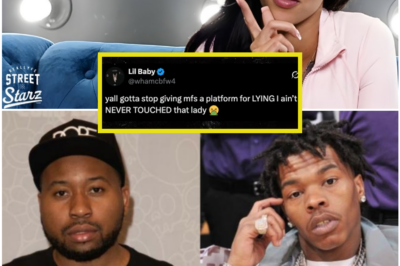

Lil Baby’s “Undeserving” Comment Sparks Firestorm as Jaw Morant Pushes Back Against Viral Narratives

When One Comment Goes Viral: How Lil Baby and Jaw Morant Became the Center of an Online Culture War The…

21 Savage’s Call for Peace Reignites Questions Around Young Thug and Gunna’s Fractured Bond

21 Savage’s Words Force the Young Thug–Gunna Tension Into the Spotlight Again In a genre built on loyalty, silence, and…

Wiz Khalifa and Romania: The Unclear Case Behind the Rumored 9-Month Sentence

From Global Icon to Legal Uncertainty: Why Wiz Khalifa’s Name Is Dominating Headlines In recent days, the name Wiz Khalifa…

Drake’s Rolls-Royce Christmas Gift to BenDaDonnn Sparks Praise, Backlash, and Unanswered Questions

Why Drake’s Christmas Surprise for BenDaDonnn Has the Internet Divided In the final days leading up to Christmas, when social…

Chris Brown Surpasses Michael Jackson in U.S. Sales, Igniting a Cultural Firestorm

A New King or a Misleading Crown? Chris Brown’s Record Sparks Global Debate The comparison was inevitable, yet few expected…

Lil Wayne’s Unexpected Performance Ignites Debate Over Hip-Hop’s Voice and Future

A Moment That Stopped the Industry: Why Lil Wayne’s Latest Appearance Still Divides Audiences For weeks, the industry moved as…

End of content

No more pages to load