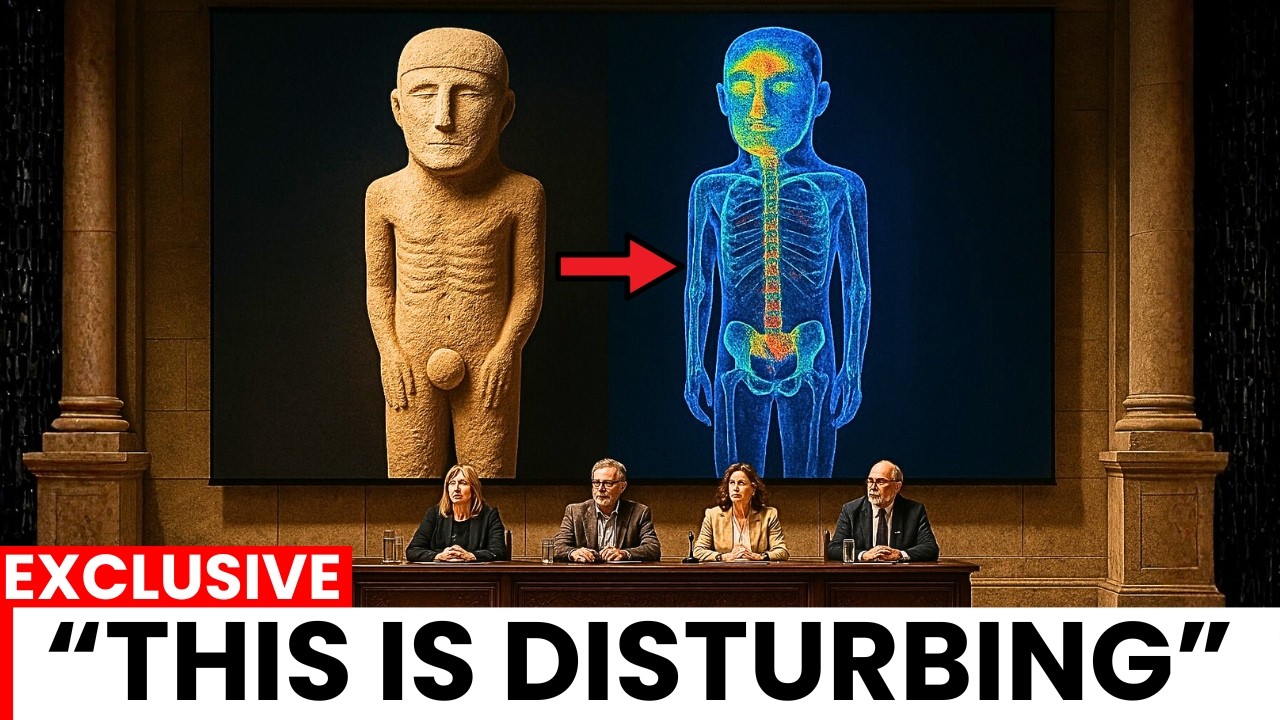

What Archaeologists Aren’t Saying About the Human Figure Found at Göbekli Tepe May Be the Most Disturbing Part

The news did not arrive with a press conference or an official academic paper.

It surfaced quietly, almost carelessly, through fragments of conversation, leaked photographs, and cautious wording from researchers who suddenly became reluctant to speak on record.

Somewhere beneath the sunbaked limestone of southeastern Turkey, inside the already controversial site of Göbekli Tepe, archaeologists are said to have encountered something that refuses to fit comfortably into the story humanity tells about itself: a human statue, dated to nearly 12,000 years ago, emerging from a time when humans were never supposed to carve themselves in stone with such intent.

Göbekli Tepe has never been an easy site to explain. Long before this alleged discovery, it had already forced historians to reconsider the origins of civilization.

Massive stone pillars, some weighing several tons, were erected by societies officially classified as hunter-gatherers.

There were no cities, no agriculture in the modern sense, no written language—yet the architecture suggested planning, cooperation, and belief systems of startling complexity.

Scholars reluctantly adjusted timelines.

Civilization, they admitted, might have begun earlier than expected.

But even those revisions came with limits.

Human representation, particularly lifelike or symbolic statues, was still considered a later development.

Until now.

According to multiple sources familiar with the excavation, the statue was not immediately recognizable as extraordinary.

It was partially buried, damaged by time, its surface eroded just enough to invite doubt.

But as layers of sediment were removed, the outline became clearer.

This was not an animal, not an abstract symbol, not a decorative motif.

It was unmistakably human. A head, a torso, arms positioned in a deliberate posture.

Not expressive in a modern sense, but intentional. Watching. Waiting.

What has unsettled researchers most is not merely the age attributed to the statue, but the way it appears to have been placed.

It was not discarded or randomly positioned.

It seems to have occupied a specific location, aligned with surrounding structures, as if meant to be seen, approached, perhaps even confronted.

Some archaeologists have reportedly described a sense of unease when the form became fully visible—a reaction quickly dismissed in public statements, but harder to ignore in private discussions.

Official channels have been careful.

No definitive claims. No dramatic conclusions.

Just words like “preliminary,” “under review,” and “context-dependent.” Yet behind that caution lies a growing tension.

If the statue is authentic and accurately dated, it challenges more than artistic timelines. It raises questions about social hierarchy, identity, and self-awareness at a stage of human development long portrayed as simple and egalitarian.

The problem is not that early humans could carve stone. That much has been accepted. The problem is what they chose to carve.

Human figures imply self-reflection. They imply the concept of the individual, or perhaps the authority of a particular role.

Some researchers speculate that the statue could represent a leader, a shaman, an ancestor, or something less comfortable to name.

Others push back, arguing that modern observers are projecting meaning where none exists, turning erosion into intention and coincidence into symbolism.

But even skeptics admit something feels different about this object.

The posture of the figure has become a focal point of debate.

It is not passive. It does not lie flat or blend into the surrounding stonework.

The arms, according to descriptions circulating among academic circles, appear positioned in a way that suggests control or command.

The face, though worn, lacks softness. There is no attempt at decoration, no effort to beautify.

It is stark. Purposeful.

Some have described it as confrontational, though no one seems eager to explain exactly why.

As word of the find spread beyond the excavation team, speculation filled the silence left by official restraint.

Online forums lit up with theories ranging from lost civilizations to forgotten belief systems.

More extreme voices whispered about suppressed knowledge and rewritten history.

Mainstream archaeologists dismissed these ideas quickly, but not before they gained traction.

In the absence of clear information, mystery thrives.

What makes the situation more volatile is Göbekli Tepe’s reputation.

The site has already been used, fairly or not, as a symbol of everything archaeology “got wrong” about early humanity.

Every new discovery there carries amplified weight.

A human statue does not exist in isolation; it stacks atop decades of unresolved questions.

Why build monumental structures before farming? Why invest so much effort into ritual spaces? And now, why immortalize the human form at such an early stage?

Some experts quietly suggest that the statue could point to a stratified society—an idea that makes many uncomfortable.

Hierarchy implies power. Power implies control. Control implies conflict.

These are concepts traditionally associated with later, more “advanced” societies.

If they existed 12,000 years ago, then the line between “primitive” and “civilized” begins to blur beyond recognition.

Others warn against overinterpretation.

They argue that one object cannot rewrite history, that dating may change, that context may soften its implications.

But even these cautious voices acknowledge the psychological impact of the discovery.

Once seen, it cannot be unseen. Once imagined, it cannot be easily dismissed.

Adding to the unease is the delay in releasing comprehensive documentation.

While some argue this is standard procedure, others find the silence unsettling.

In an age of instant information, waiting feels suspicious.

Every day without clarification fuels further debate, further division between institutional authority and public curiosity.

Meanwhile, the statue itself remains largely hidden from view, accessible only to a limited group of researchers.

Photographs, if they exist, have not been widely circulated. Descriptions vary subtly depending on who is speaking.

Those differences, small as they are, have become cracks through which doubt and intrigue seep.

Is it possible that early humans understood themselves more deeply than we assumed? That they grappled with identity, leadership, fear, and belief in ways that mirror our own struggles today? Or is this statue being elevated beyond its significance because we are desperate for mystery, for disruption, for proof that history is more dramatic than textbooks suggest?

The truth, for now, sits buried between stone and silence. What is certain is that this discovery has reopened a conversation many thought was settled.

It has reminded the academic world that archaeology is not just about objects, but about narratives—and narratives are fragile.

One unexpected artifact can destabilize decades of consensus.

As researchers continue their work behind closed doors, the public waits.

Some with excitement. Some with skepticism. Some with an unease they cannot quite explain.

The statue at Göbekli Tepe does not speak, but it does not need to.

Its presence alone asks a question that refuses to go away. What if we have underestimated ourselves from the very beginning? And what if that misunderstanding was never accidental?

Only time, and transparency, will tell whether this human figure becomes a footnote, a correction, or a fracture line in the story of humanity.

Until then, the silence surrounding it may be the most unsettling clue of all.

News

Lil Baby’s “Undeserving” Comment Sparks Firestorm as Jaw Morant Pushes Back Against Viral Narratives

When One Comment Goes Viral: How Lil Baby and Jaw Morant Became the Center of an Online Culture War The…

21 Savage’s Call for Peace Reignites Questions Around Young Thug and Gunna’s Fractured Bond

21 Savage’s Words Force the Young Thug–Gunna Tension Into the Spotlight Again In a genre built on loyalty, silence, and…

Wiz Khalifa and Romania: The Unclear Case Behind the Rumored 9-Month Sentence

From Global Icon to Legal Uncertainty: Why Wiz Khalifa’s Name Is Dominating Headlines In recent days, the name Wiz Khalifa…

Drake’s Rolls-Royce Christmas Gift to BenDaDonnn Sparks Praise, Backlash, and Unanswered Questions

Why Drake’s Christmas Surprise for BenDaDonnn Has the Internet Divided In the final days leading up to Christmas, when social…

Chris Brown Surpasses Michael Jackson in U.S. Sales, Igniting a Cultural Firestorm

A New King or a Misleading Crown? Chris Brown’s Record Sparks Global Debate The comparison was inevitable, yet few expected…

Lil Wayne’s Unexpected Performance Ignites Debate Over Hip-Hop’s Voice and Future

A Moment That Stopped the Industry: Why Lil Wayne’s Latest Appearance Still Divides Audiences For weeks, the industry moved as…

End of content

No more pages to load