Maps, Myths, and Missing Gold: The Dangerous Question of What the Aztecs Took With Them When History Looked Away

For centuries, the story of the Aztec Empire has been told as a tragedy sealed in the ruins of Tenochtitlán, its gold melted down, shipped across oceans, and absorbed into the vaults of Europe.

That is the version most people know.

It is clean. It is convenient.

And according to a growing number of researchers, explorers, and quiet insiders, it may be dangerously incomplete.

Because some stories refuse to stay buried.

In the final months before the fall of the Aztec capital in 1521, chaos ruled the empire.

Spanish forces tightened their grip. Allies turned into executioners. Gold—vast quantities of it—became both a weapon and a liability.

Chroniclers of the conquest recorded that enormous amounts of treasure simply vanished during the retreat known as La Noche Triste.

What was recovered never matched what had been taken.

Spanish records hint at convoys that never arrived.

Indigenous accounts speak of sacred wealth hidden far from the invaders, sent north under orders meant to save not just gold, but memory itself.

And that is where the story begins to fracture.

The idea that Aztec gold could have traveled far beyond central Mexico has long been dismissed as fantasy.

Yet scattered across the American Southwest are anomalies that do not fit comfortably into accepted timelines.

Spanish-era maps referencing lands far north of New Spain surfaced in private collections, marked with symbols that resemble neither Christian iconography nor European cartography.

Some maps show rivers that resemble the Colorado long before it was officially “discovered.

” Others include cryptic notes about “red lands,” “stone guardians,” and routes where “men were lost but the cargo survived.”

Utah appears in none of the official histories. But it appears again and again in the margins.

Local legends in parts of southern Utah speak of foreign men centuries ago—men with metal armor, strange animals, and an obsession with caves.

Indigenous oral histories, rarely cited in academic texts, describe groups passing through under extreme secrecy, leaving behind sealed chambers and warnings meant for generations not yet born.

In some accounts, these travelers were not conquerors but carriers, burdened by something so valuable it brought death wherever it paused too long.

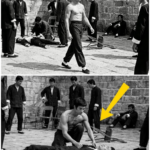

What unsettles researchers is not just the stories, but the physical markers.

Across remote desert regions, stone alignments and symbols have been found that do not match known Native American traditions of the area.

Some resemble Mesoamerican glyphs in form but not in meaning.

Others appear deliberately altered, as if designed to mislead anyone who tried to read them too directly.

A few sites were quietly restricted after amateur archaeologists began asking the wrong questions.

Official explanations followed.

Geological instability.

Cultural sensitivity.

Environmental protection.

The reasons sounded reasonable. They always do. Then there are the disappearances.

Over the last century, more than a dozen treasure hunters and independent researchers claimed they were close to confirming a “southern origin” cache hidden somewhere in Utah.

Some abandoned their searches abruptly.

Others stopped speaking publicly altogether.

A handful died under circumstances that raised eyebrows but closed cases.

Their notes, when recovered, often ended the same way: partial maps, references to “Spanish tunnels,” and a recurring phrase written in different hands across decades—“too far north to be believed.”

Skeptics argue that this is nothing more than the human appetite for myth, dressed up in coincidence.

They point out the logistical impossibility of transporting tons of gold across hostile terrain without leaving undeniable proof.

They remind us that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

And yet, even within official archives, there are gaps no one seems eager to fill.

Entire shipments unaccounted for.

Testimonies that contradict financial records.

Letters from conquistadors complaining that what was promised in Mexico never reached Spain.

One former museum consultant, speaking anonymously, once remarked that the strangest part wasn’t the lack of proof—but how aggressively the idea was dismissed.

“Bad theories usually die quietly,” he said.

“This one gets buried.”

The question lingers in uncomfortable places.

If the Aztecs did move their gold north, they would have done so knowing the land would be unfamiliar, hostile, and far from Spanish control.

They would have chosen places defined by natural barriers, sacred geography, and silence.

Utah’s canyons, mesas, and hidden cave systems fit that logic too well for some to ignore.

Vast areas remain unexplored even today, not because they are unreachable, but because access is quietly discouraged.

There is also the matter of timing.

Recent satellite surveys, conducted for unrelated geological studies, revealed anomalies beneath certain desert plateaus—rectangular voids, unnatural angles, sealed chambers inconsistent with natural cave formation.

The data was categorized, filed, and moved on from.

No public excavation followed. No press release.

Just silence. Silence has become a recurring character in this story.

Those who push too hard often find doors closing.

Funding evaporates.

Permits stall.

Colleagues distance themselves.

It is never framed as suppression—just caution.

Preservation. Responsibility.

But privately, some admit there are places where digging is not encouraged, not because nothing is there, but because too many questions would follow if something was found.

And perhaps that is the most unsettling possibility of all. If the gold exists, it challenges more than treasure maps.

It forces a reconsideration of how far Aztec influence may have reached, how much indigenous knowledge has been filtered through colonial lenses, and how history decides which stories are allowed to survive.

Gold is never just gold.

It is power, proof, and narrative control.

Whoever finds it does not simply become rich.

They become inconvenient. So the debate continues, half in daylight, half in whispers.

On one side, official history stands firm, insisting the Aztec gold is long gone, accounted for, dissolved into modern economies.

On the other, a growing underground consensus suggests that not everything was lost—some of it was hidden, deliberately and brilliantly, beyond the imagination of those who came looking too late.

Whether Utah holds the answer remains unconfirmed.

No photograph, no artifact, no public discovery has settled the question.

But the absence of resolution is precisely what keeps the story alive.

In deserts where echoes travel farther than truth, where stone remembers what paper forgets, one question refuses to disappear.

What if the greatest treasure of the Aztec Empire was never meant to be found—only waited for?

And if it is still there, buried beneath layers of sand, secrecy, and denial, the more dangerous question may not be who will discover it… but who already has.

News

Lil Baby’s “Undeserving” Comment Sparks Firestorm as Jaw Morant Pushes Back Against Viral Narratives

When One Comment Goes Viral: How Lil Baby and Jaw Morant Became the Center of an Online Culture War The…

21 Savage’s Call for Peace Reignites Questions Around Young Thug and Gunna’s Fractured Bond

21 Savage’s Words Force the Young Thug–Gunna Tension Into the Spotlight Again In a genre built on loyalty, silence, and…

Wiz Khalifa and Romania: The Unclear Case Behind the Rumored 9-Month Sentence

From Global Icon to Legal Uncertainty: Why Wiz Khalifa’s Name Is Dominating Headlines In recent days, the name Wiz Khalifa…

Drake’s Rolls-Royce Christmas Gift to BenDaDonnn Sparks Praise, Backlash, and Unanswered Questions

Why Drake’s Christmas Surprise for BenDaDonnn Has the Internet Divided In the final days leading up to Christmas, when social…

Chris Brown Surpasses Michael Jackson in U.S. Sales, Igniting a Cultural Firestorm

A New King or a Misleading Crown? Chris Brown’s Record Sparks Global Debate The comparison was inevitable, yet few expected…

Lil Wayne’s Unexpected Performance Ignites Debate Over Hip-Hop’s Voice and Future

A Moment That Stopped the Industry: Why Lil Wayne’s Latest Appearance Still Divides Audiences For weeks, the industry moved as…

End of content

No more pages to load