If the Map Is Real, Everything Changes: Graham Hancock and the Evidence History Refuses to Confront

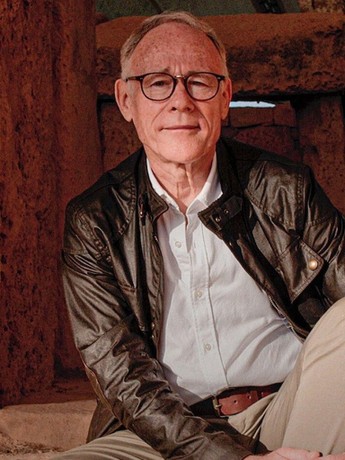

For decades, Graham Hancock has occupied a strange position in the public imagination.

Too controversial for mainstream academia, too persistent to be dismissed, he has continued to return to the same uncomfortable claim: that the official story of human history is incomplete, selectively edited, and guarded with an intensity that suggests more than simple academic disagreement.

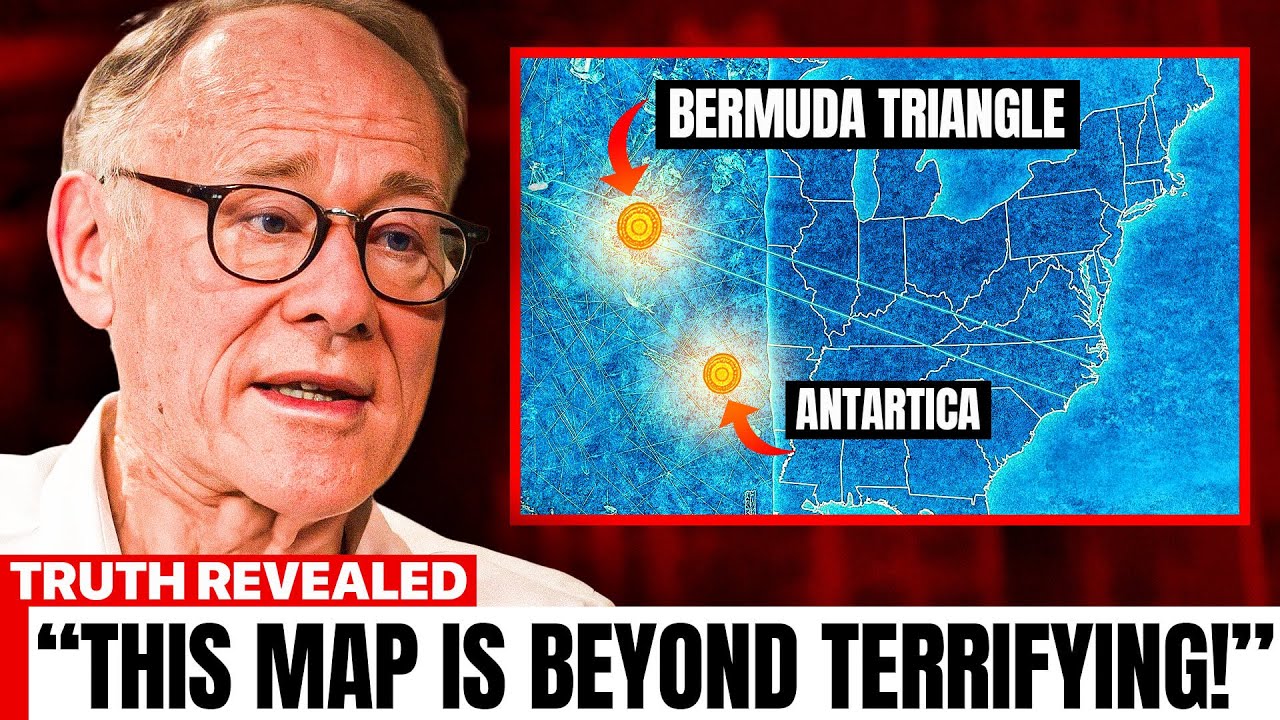

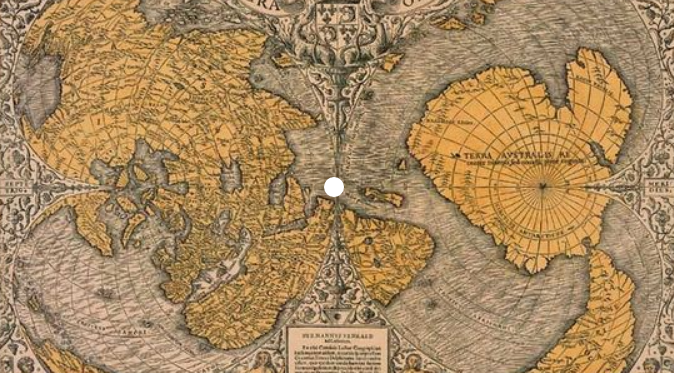

This time, the focus is a world map. Not a symbolic map. Not a mythological diagram.

A map that, according to Hancock, depicts the Earth with an accuracy that should not exist within the accepted timeline of civilization.

The controversy did not begin with a dramatic unveiling or a press conference.

It began quietly, as these things often do, with references buried in old archives, marginal notes in forgotten texts, and maps that appeared briefly in scholarly discussions before being labeled “anomalous” and quietly set aside.

Hancock claims that this particular map, or rather a class of maps derived from the same lost source, shows geographical knowledge that predates known navigation technologies.

Coastlines appear as they would have looked before the last Ice Age.

Landmasses now submerged are drawn with unsettling precision.

In some versions, Antarctica is depicted without ice, a detail that alone sends shockwaves through established chronologies.

According to Hancock, the reaction to these maps follows a predictable script.

Initial curiosity gives way to discomfort. Discomfort hardens into dismissal. Dismissal is then formalized into consensus.

The maps are described as coincidental, distorted, or the result of later alterations.

Any suggestion that they might represent inherited knowledge from a much older civilization is labeled speculative at best, dangerous at worst.

Yet Hancock insists that what is dangerous is not the idea itself, but the refusal to examine it honestly.

He argues that the problem is not a lack of evidence, but a lack of permission.

Certain questions are allowed to be asked. Others are quietly discouraged. Funding dries up.

Careers stall.

Researchers learn, often without being told directly, where the invisible boundaries lie.

The map, Hancock says, sits precisely on one of those boundaries.

To accept it as authentic would mean admitting that ancient humans possessed advanced surveying skills, global navigation knowledge, and perhaps a shared understanding of the planet that contradicts the narrative of isolated, primitive cultures slowly stumbling toward progress.

Critics respond that Hancock is connecting dots that do not belong together.

They argue that ancient mapmakers could have extrapolated coastlines, copied errors from one source to another, or relied on imagination rather than measurement.

These explanations, while plausible in isolation, become harder to sustain when similar features appear across multiple maps from different regions and eras.

Hancock does not claim certainty. He claims pattern.

And patterns, he notes, are precisely what established history tends to avoid when they threaten foundational assumptions.

What makes the debate especially volatile is the implication that the map is not merely a curiosity, but a fragment of something larger.

Hancock suggests that it may be a copy of copies, derived from an original source created by a civilization that existed before the last great climatic catastrophe.

A civilization that understood the Earth as a whole, not as disconnected continents.

A civilization that may have been wiped out, leaving behind only echoes of its knowledge encoded in myths, monuments, and, occasionally, maps that should not exist.

The idea is unsettling because it reframes humanity’s story.

Instead of a simple upward trajectory from ignorance to enlightenment, it suggests cycles of rise and collapse.

Knowledge gained, lost, and partially recovered.

It suggests that modern civilization is not the first to look out at the world with sophisticated eyes, but merely the latest.

For many scholars, this is not just unproven. It is heretical.

Hancock’s supporters argue that the hostility toward these ideas reveals more about institutional fragility than scientific rigor.

They point out that history is rewritten all the time when new evidence emerges, yet certain topics remain unusually resistant to revision.

Why, they ask, is the possibility of ancient advanced knowledge treated with such disdain, when equally radical ideas in other fields are celebrated as breakthroughs? The answer, Hancock implies, lies in power.

Whoever controls the narrative of the past also controls the framework through which the present is understood.

The map itself has become almost secondary to what it represents. Hancock claims he has been warned, informally but unmistakably, to tread carefully.

Not threatened in a cinematic sense, but cautioned. Advised to soften his language.

Encouraged to present his ideas as entertainment rather than investigation. He has refused.

In interviews, he speaks with the calm insistence of someone who believes that silence is the greater danger.

He emphasizes that he is not asking for belief, but for examination.

Open archives. Transparent debate. Willingness to follow evidence wherever it leads, even if it leads somewhere uncomfortable.

He points out that many breakthroughs in science were initially ridiculed, not because they lacked evidence, but because they disrupted existing hierarchies.

The map, he suggests, is disruptive in precisely that way. There is also a cultural dimension to the controversy.

If ancient civilizations possessed global knowledge, then the story of “discovery” changes.

It becomes less about heroic explorers venturing into the unknown and more about rediscovery.

This challenges deeply ingrained narratives of progress, conquest, and superiority.

It also raises questions about whose knowledge was preserved and whose was erased.

Skeptics maintain that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Hancock does not disagree.

He simply counters that extraordinary evidence cannot be evaluated if it is dismissed before being studied. He argues that the map deserves serious, interdisciplinary analysis, not reflexive debunking.

Geography, climatology, archaeology, and mythology, he believes, all have a role to play in understanding its origins.

As the debate intensifies, the map has taken on a symbolic weight.

It represents a fault line between two ways of viewing history.

One sees the past as settled, with only minor adjustments needed at the edges.

The other sees it as provisional, a story still being pieced together from fragments that challenge comfortable assumptions.

Hancock stands firmly on the fault line, refusing to step back.

Whether the map ultimately proves to be a revolutionary artifact or an elaborate misunderstanding remains unresolved.

What is clear is that it has reopened questions many thought were closed.

Questions about how much we truly know about our ancestors. Questions about how knowledge survives catastrophe. Questions about who decides which histories are taught and which are forgotten.

In revealing the map again, Hancock is not offering closure.

He is offering provocation. He is inviting scrutiny while accusing the gatekeepers of fearing it.

The tension between those positions continues to grow, fueled by public curiosity and institutional resistance.

The map, silent and unassuming, sits at the center of the storm, asking nothing, yet demanding everything.

And perhaps that is what unsettles people the most.

Not that the map might be wrong, but that it might be right, and that its implications extend far beyond geography.

Into memory. Into identity.

Into the fragile agreement we call history.

News

Lil Baby’s “Undeserving” Comment Sparks Firestorm as Jaw Morant Pushes Back Against Viral Narratives

When One Comment Goes Viral: How Lil Baby and Jaw Morant Became the Center of an Online Culture War The…

21 Savage’s Call for Peace Reignites Questions Around Young Thug and Gunna’s Fractured Bond

21 Savage’s Words Force the Young Thug–Gunna Tension Into the Spotlight Again In a genre built on loyalty, silence, and…

Wiz Khalifa and Romania: The Unclear Case Behind the Rumored 9-Month Sentence

From Global Icon to Legal Uncertainty: Why Wiz Khalifa’s Name Is Dominating Headlines In recent days, the name Wiz Khalifa…

Drake’s Rolls-Royce Christmas Gift to BenDaDonnn Sparks Praise, Backlash, and Unanswered Questions

Why Drake’s Christmas Surprise for BenDaDonnn Has the Internet Divided In the final days leading up to Christmas, when social…

Chris Brown Surpasses Michael Jackson in U.S. Sales, Igniting a Cultural Firestorm

A New King or a Misleading Crown? Chris Brown’s Record Sparks Global Debate The comparison was inevitable, yet few expected…

Lil Wayne’s Unexpected Performance Ignites Debate Over Hip-Hop’s Voice and Future

A Moment That Stopped the Industry: Why Lil Wayne’s Latest Appearance Still Divides Audiences For weeks, the industry moved as…

End of content

No more pages to load