Woody Allen at 89 years old broke his

silence not through a press release not

through a statement but through private

conversations that are now coming to

light sources close to the legendary

director say he was extremely distraught

and surprised by her death but here’s

what’s curious why surprised

you know privacy issues abortion issues

um an enormous amount of pressure from

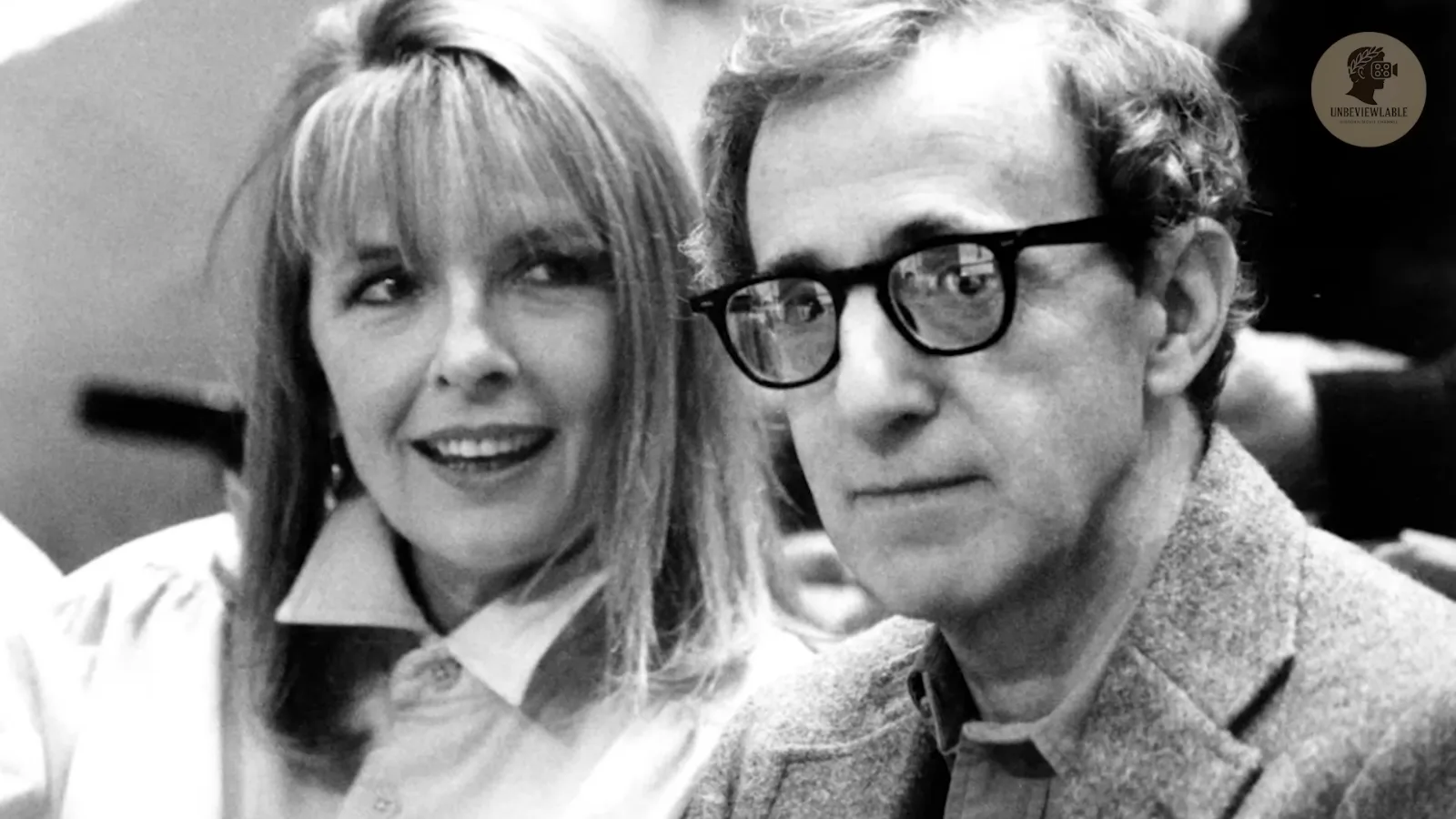

they’d known each other for 56 years.

They’d made nine films together. She’d

been his greatest muse, his most loyal

defender, and the woman who never truly

left his life. What Allan is revealing

now in the wake of her passing changes

everything we thought we knew about

their relationship.

Are people who are self-d deluded, who

are

This isn’t just about a director and his

actress. This is about a love so

complicated, so messy, so real that it

couldn’t survive as romance, but refused

to die as connection.

Did you take it seriously?

I took it seriously in the middle of the

night when you get a phone call at 4 in

the morning saying that you’re going to

be killed or that

for decades we saw their relationship

through the lens of Annie Hall, through

the romantic comedies, through the

public image.

A relationship, I think, is is like a

shark. You know, it has to constantly

move forward or it dies. The truth is

far more complex, far more painful, and

far more human than anything Allan ever

put on screen. She stood by him when the

entire world turned away. She defended

him when it cost her everything.

Dah la dah la. Yeah.

And now at 89, facing his own mortality,

Allan is finally telling the real story.

The story of the woman who saved him,

the love he couldn’t hold on to, and the

regrets that haunt him still. It was

1969 and Woody Allen was casting his

Broadway play, Play It Again, Sam. He’d

seen dozens of actresses, all talented,

all beautiful, all forgettable. Then

Diane Keaton walked in. She was 23 years

old, fresh from California, wearing

clothes that didn’t quite match and

speaking in a way that made no logical

sense, but somehow felt completely

honest. Alan later described that first

impression in words that would prove

prophetic. He called her adorable,

funny, totally original in style, real,

fresh. But what he didn’t say publicly,

what friends reveal now, is that he was

terrified. Terrified because she was

everything he wasn’t. She was light

where he was dark, optimistic where he

was cynical, free where he was

imprisoned by his own neurosis. He cast

her on the spot, not just because she

was right for the role, but because he

couldn’t imagine not seeing her again.

Within weeks, they were dating. Within

months, she’d moved into his apartment.

Their friends gave the relationship 6

months, maybe less. How could it

possibly work? He was the neurotic

Jewish intellectual from Brooklyn who

analyzed everything to death. She was

the California girl who said, “Leah,”

and meant it sincerely. He lived in his

head. She lived in the moment. He

collected anxieties. She collected joy.

But somehow, impossibly, it worked. At

least for a while. Those early years,

1969 to 1971, were the happiest of

Allen’s life. He’d admit this decades

later to close friends. With Diane, he

felt seen. Not as Woody Allen, the

comedian, not as the director, not as

the public persona, just as Alan

Coningsburg, the scared kid from

Brooklyn who never felt good enough. She

had this way of looking at him, really

looking at him and making him feel like

maybe he was okay after all. They’d walk

through Central Park for hours. She’d

point at things, clouds, dogs, children

playing, and find wonder in the

everyday. He’d never understood that

before. How someone could just be happy

without reason, without analysis,

without needing to understand why. She

taught him that or tried to because the

truth is he couldn’t learn it. His

nature wouldn’t allow it. Living

together revealed the cracks. Allan was

controlling in ways that seemed loving

but weren’t. He wanted to know where she

was, who she talked to, what she was

thinking. Every moment he’d rewrite her,

try to make her more sophisticated, more

intellectual, more like the women in his

films. But Diane resisted. Not

aggressively. That wasn’t her style. She

resisted by simply remaining herself.

When he’d correct her grammar, she’d

smile and say the wrong thing again.

When he’d suggest better books to read,

she’d stick with her photography

magazines. When he’d criticize her

fashion choices, she’d wear even more

bizarre combinations the next day. It

drove him crazy. It also made him love

her more. She was the one thing in his

life he couldn’t control, couldn’t

direct, couldn’t reshape into his

vision, and that’s what made her

dangerous. Friends from that era

remember the arguments. Not screaming

matches. Allan didn’t do those, but cold

intellectual takedowns where he’d

dissect her thoughts, her choices, her

very way of being, and she’d just look

at him with those eyes and say something

like, “You think too much, which would

make him even more furious because she

was right.” The breaking point came in

1971.

Francis Ford Copala was casting The

Godfather. Through connections, Diane

got an audition for K. Corleó. She

almost didn’t go. Allan was dismissive.

It’s a gangster movie, not your style.

You’re doing Play It Again, Sam with me.

But something made her go anyway. Maybe

Curiosity, maybe Instinct, maybe the

first Whisper of Rebellion. She got the

part. She hadn’t even read the script

when she accepted. Years later, she’d

admit this publicly. How bad is that? I

didn’t even really read it, but I needed

a job. And that’s what she said. But

people close to them knew the truth. She

needed more than a job. She needed

escape. When she told Alan she was

taking the role, that she’d be in

California for months, that she’d miss

his film, he didn’t yell. He went

silent. The cold, wounded silence that

was worse than any argument. “You’re

choosing Copala over me,” he said

finally. “You’re choosing them over us.”

She tried to explain. It’s not about

choosing. It’s about my career, my life.

But he couldn’t hear it. To Allan, it

was betrayal. Plain, simple,

unforgivable. She left anyway. And

something between them broke that never

fully healed. While Diane was filming

The Godfather, something else happened

that Alan would obsess over for years.

She fell for Alpuccino. Not immediately,

not obviously, but it was there. The

chemistry on screen was real because the

attraction offscreen was real. Pacino

was everything Allan wasn’t. Physically

present, emotionally intense,

dangerously charismatic. Where Allan

intellectualized, Pacino felt. Where

Allan analyzed, Pacino acted. And Diane,

who’d spent two years being subtly

molded by Allen’s controlling nature,

found in Pacino a different kind of

energy entirely. They didn’t start

dating then, not officially. But the

seed was planted and Allan knew it. He

could see it in the rushes, in the way

she looked at Pacino on screen. Friends

say Allan became obsessed with The

Godfather during its production. He’d

ask mutual acquaintances about the

shoot, about Diane, about her co-stars.

He’d probe subtly, trying to understand

what was happening 3,000 mi away. When

she returned to New York, things were

different. More confident, more sure of

herself, less willing to defer to his

judgment. She’d been directed by Copola,

acted opposite Pacino and Brando, been

part of something massive and important.

Allan’s intellectual comedy suddenly

felt small by comparison. They tried to

make it work. She starred in his next

film, then the next. But the dynamic had

shifted. She wasn’t his discovery

anymore, his creation, his proteéé. She

was a movie star in her own right, and

Allan couldn’t handle it. The

relationship officially ended in 1972,

though accounts vary on who ended it.

Alan claimed it was mutual. Friends say

Diane left. What certain is this? She

was tired. Tired of being analyzed,

tired of being improved, tired of

feeling like a project instead of a

partner. She wanted to be loved for who

she was, not who she could become. And

Allan couldn’t give her that. He loved

the idea of her, the character of her,

the role of her in his life. But the

real Diane, messy and illogical and

beautifully chaotic, that scared him too

much. You’d think that would be the end.

A relationship ends. People move on.

Time passes. But Woody Allen doesn’t

work that way. In 1977, 5 years after

their breakup, he made Annie Hall, and

he made sure Diane Keaton starred in it.

The film was about their relationship,

not loosely based on, not inspired by,

but actually about them. Scene after

scene, pulled from real life. The

arguments were real arguments. The

awkward moments were their awkward

moments. Even the name Annie Hall came

from her. Annie was her real nickname.

Hall was her birth surname before she

changed it to Katon. Allan wrote the

part so specifically for her that no

other actress could have played it. He

even had her wear her own clothes from

when they’d dated. Those famous outfits,

the ties and vests and oversized men’s

wear, that was actually how she dressed.

He was putting their relationship on

screen, every intimate detail, every

private moment, every flaw, and making

her perform it for the world. Some

called it genius. Others called it

exploitation. Diane called it weird and

painful. But she did it anyway because

despite everything, despite the

controlling behavior and the emotional

manipulation and the way he dissected

their love, she still trusted him as a

director. She still believed in his

vision and maybe some part of her wanted

to preserve what they’d had, even if it

was through the distorted lens of his

art. The film became a phenomenon. It

won best picture. She won best actress.

And suddenly the whole world knew their

story or thought they did because the

film wasn’t really true. Alan had

rewritten the ending. In real life,

their breakup had been messy and painful

and unresolved. In Annie Hall, it was

bittersweet and philosophical and

somehow romantic. He’d taken their

failure and made it beautiful. He’d

taken her rejection and made it mutual.

He’d rewritten history to be more

palatable, more poetic, more worthy of

his artistic vision. And she let him.

Years later, Allan would admit to

friends what the film really was. It

wasn’t a love letter. It was an

exorcism. He was trying to purge her

from his system, to understand why it

didn’t work, to somehow make peace with

losing her. But here’s the thing about

exorcisms. Sometimes they don’t work.

Sometimes the ghost stays. Sometimes

you’re haunted forever. After Annie

Hall, a strange thing happened. Their

romantic relationship was over

definitively, permanently, completely.

But their professional relationship,

that was just beginning. Between 1978

and 2020, Diane Keaton appeared in eight

more Woody Allen films. Manhattan in

1979, just 2 years after Annie Hall.

Manhattan Murder Mystery in 1993, over

two decades later, and several others

spanning 42 years. Think about that for

a moment. 42 years of working together

after the romance ended, 42 years of

seeing each other on set, of him

directing her, of them creating art

together while maintaining careful

emotional distance. It was an

arrangement that shouldn’t have worked,

but somehow did. Friends say there was

an unspoken understanding between them.

She could have other relationships,

other loves, other lives. But on film,

she was his and he needed that. He

needed her in his work even if he

couldn’t have her in his life. That’s

what he told a close friend once. Every

other actress was compared to her. Every

other performance measured against the

standard she set. He’d work with

brilliant women, Mia Pharaoh, Diane

Wuest, Scarlett Johansson, Kate

Blanchett, but none of them were Diane.

None of them had that particular magic,

that specific quality that made his

words come alive in ways even he hadn’t

imagined. This arrangement took its toll

on her other relationships, especially

with Alpuccino. Their on-again,

off-again romance lasted 15 years from

1974 to 1990. And throughout it all,

Allan was there. Not physically, but as

a presence, a ghost, a comparison.

Pacino couldn’t escape. She’d leave to

do a Woody Allen film. She’d talk about

Woody’s genius, Woody’s vision, Woody’s

brilliance. And Pacino, secure as he

was, felt himself competing with

something he couldn’t fight. How do you

compete with someone who’s already lost?

That’s what Allan was. He’d already lost

her romantically, so there was no

threat, no danger, no competition. But

emotionally, creatively, that connection

remained unbreakable. Pacino wanted

marriage, wanted commitment, wanted her

full attention. She couldn’t give it.

Not because she didn’t love him. She was

mad for him, she’d say later, but

because some part of her was still tied

to Allen in ways she couldn’t explain or

escape. Then came 2014 and everything

changed. Dylan Pharaoh’s accusations

against Woody Allen resurfaced. The

details were devastating. The

allegations horrific. Hollywood began

distancing itself from Allen

immediately. Actors who’d worked with

him issued statements. Directors who’d

admired him went silent. Awards

ceremonies stopped honoring him. By

2018, with the MeToo movement in full

force, Allan had become Hollywood’s

pariah. Everyone abandoned him. Everyone

except Diane Keaton. In January 2018,

she tweeted something that would define

the rest of her public life. Woody Allen

is my friend and I continue to believe

him. Just 13 words that destroyed

relationships, cost her roles, and made

her a target of public fury. Jud

Appattow attacked her publicly. Dylan

Pharaoh’s supporters called her an

enabler. Think pieces were written about

how disappointing she was, how her

loyalty was misplaced, how she was on

the wrong side of history. She lost

work. Films that would have cast her

went to other actresses. Directors who’d

wanted to work with her suddenly

couldn’t make it happen. Friends in the

industry stopped calling. She became, in

many ways, as controversial as Allen

himself. But she wouldn’t back down. In

2023, 5 years into the controversy, she

gave an interview that made things

worse. When asked if working with Allan

overshadowed her career, she said, “No,

not at all. I’m proud. I’m proud beyond

measure.” Then she said something that

sparked immediate outrage. She dismissed

Survivor Culture as a horrible shame,

then added, “You got to get over it.”

The backlash was swift and brutal, but

she didn’t apologize, didn’t clarify,

didn’t walk it back. What made her so

fiercely, stubbornly, destructively

loyal to a man she hadn’t even dated in

over 50 years? Allan never asked her to

defend him, never requested her support,

never demanded her loyalty. She gave it

freely at great personal cost because of

something most people couldn’t

understand. She believed him, not

blindly, not naively, but after knowing

him for five decades, after seeing him

at his worst and his best, after being

in his life more consistently than

almost anyone, she looked at the

accusations and didn’t believe them.

Maybe she was wrong. Maybe her loyalty

was misplaced. But it was real and it

was chosen. She knew what it would cost

her and she paid that price willingly.

Throughout 2024, Diane Katon’s health

was declining rapidly. She kept it

private, almost completely hidden, even

from close friends. There were signs for

those who looked closely. She’d lost

weight, appeared frail in her few public

outings, had canled several projects

without explanation, but she never made

a public announcement, never prepared

anyone for what was coming. On October

11th, 2025, emergency services were

called to her Brentwood home at 8:08 in

the morning. She was transported to a

local hospital where she was pronounced

dead. The official announcement came

hours later. Diane Keaton, aged 79, had

passed away. No cause of death was

given, just that it had been sudden.

When Woody Allen got the call, sources

say he was stunned into silence. I

didn’t even know she was sick. He

reportedly said, “How is that possible?”

For someone he’d known for 56 years,

someone he’d worked with nine times,

someone who’ defended him when the world

turned away. He hadn’t known she was

dying. That absence of knowledge, that

gap in awareness hit him hard. He’d been

so focused on his own isolation, his own

pariah status, his own battles, that

he’d failed to see she was fighting

something far worse. The funeral was

small, private, just family and a

handful of close friends. Allan

attended, masked, hunched, looking every

one of his 89 years. He brought

something that made several attendees

cry. It was a photograph from 1970. One

of the two of them on the set of Play It

Again, Sam. They’re both laughing in it,

genuinely laughing, the kind of laughter

that comes from pure joy rather than

performance. He’d had it framed.

Merryill Streep, who attended the

service, later told a friend that Allan

couldn’t stop crying. Not quiet,

dignified tears, but deep body shaking

sobs. She’d never seen him like that.

Nobody had. Woody Allen was famous for

his emotional control, his

intellectualization of feelings, his

distance from raw emotion. But

confronted with Dian’s death, all of

that collapsed. Later, people discovered

he’d written her a letter. A long,

detailed letter explaining things he’d

never said out loud. But he’d written it

too late. She died before he could send

it. Before she could read his words, his

confessions, his truth. A few days after

Diane’s death, Woody Allen started

talking. Not publicly. He’d never do

that. But in private conversations with

old friends, with colleagues, with the

few people still in his orbit, he began

revealing things, things he’d kept

locked away for decades. Things he’d

never admitted even to himself about why

their relationship couldn’t work. He was

brutally honest. I was too controlling

and she was too free, he said. I tried

to remake her into something more

manageable and she resisted by being

more herself. I loved her, but I loved

the idea of controlling her more. That’s

not love. That’s ownership. And she was

right to leave. About Annie Hall, he

confessed something that

recontextualizes the entire film. I gave

her the Oscar, but she gave me

everything else. The film, the career,

the credibility, the soul of my work.

Without her, I’m just another neurotic

making comedies about neurotic people.

with her. I was creating something real.

About the other women in his life, he

was equally blunt. I loved Mia

differently, Sunni differently, all of

them differently. But Diane, I loved her

the most honestly. She saw the real me,

the pathetic, insecure, damaged me, and

she stayed anyway until she couldn’t

anymore because I made it impossible.

his biggest regret, the thing that

haunts him at 89 years old, facing his

own mortality. I should have just let

her be. That’s what he keeps saying to

friends. I should have just loved her

the way she was instead of trying to

make her into what I thought she should

be. I should have been grateful for the

miracle of her instead of trying to

improve it. About her defense of him

during the accusations, his response

reveals everything. She believed me when

nobody else would. She stood by me when

it cost her career, her reputation, her

relationships. She didn’t have to do

that. I never asked her to. But she did

it anyway because that’s who she was.

Loyal, stubborn, convinced of what she

believed. Just like I tried to change

her for years, the world tried to change

her in those last years. Make her

denounce me, make her apologize, make

her fall in line. And she said no. Same

as she always said no to me when I

pushed too hard. There’s also the

revelation about their last

conversation, which happened months

before her death. They’d talked on the

phone, something they did occasionally

over the years, just checking in, brief

and surface level usually. But this time

was different. She’d called him, which

was rare. And she’d said something that

stuck with him. She said, “I don’t

regret any of it. The relationship, the

films, defending you, none of it. I was

who I was, and you were who you were,

and it was what it was.” That’s very

her, you know, not analyzing it to

death, just accepting it. At 89, what

does Woody Allen want people to know

about Diane Katon? That she was right

about everything about him, about life,

about not overthinking. That Annie Hall

wasn’t the truth about their

relationship. It was his fantasy version

of it. That she was a better person than

any character he ever wrote. that she

saved him far more than he ever saved

her, despite what their films might

suggest. 56 years, nine films, one

enduring, complicated, impossible love.

That’s the story of Woody Allen and

Diane Keaton. Not a romance in the

traditional sense, not a friendship

exactly, but something more complicated

and more real than either. She was his

muse, his conscience, his defender, and

the one who got away. He was her mentor,

her tour mentor, the man she never fully

left even after she left him. The irony

isn’t lost on anyone. She never married,

dated some of Hollywood’s most eligible

men, but stayed loyal longest to the one

who couldn’t hold on to her. And he,

famous for his relationships with

younger women, for moving on quickly and

completely, never quite got over the

California girl.

Well, I mean, you don’t have to, you

know. No, I know. But but you know

what their relationship really was

defies easy categorization. It was too

messy to be romance, too intimate to be

friendship, too unresolved to be past,

too painful to be present. It was

something that exists outside normal

definitions, something that only they

fully understood. Now Alan is 89, alone

with his memories and his regrets, and

the knowledge that he can never tell her

the things he finally understands. She’s

gone and with her goes the last

connection to a version of himself he

barely recognizes now. The young

ambitious director who thought he could

shape the world to his vision. Who

thought love was about molding someone

into your ideal? Who thought control and

care were the same thing. Diane Katon’s

legacy extends far beyond the films and

the Oscar and the iconic style. She was

the woman who defined Woody Allen on

screen and off. Who gave his work its

heart, who stood by him when standing by

him meant standing alone. And maybe

that’s the truest thing about their

relationship. She saw him clearly every

flaw and failure and weakness. And she

didn’t turn away. Not when they dated,

not when they broke up, not when the

world demanded it. She stayed herself

stubbornly and completely. and in doing

so gave him something he spent his whole

life trying to capture on film. The

miracle of being loved exactly as you

are. In Hollywood’s long and storied

history, there’s never been anything

quite like Woody and Diane. Before we

go, if you found this story as

fascinating as we did putting it

together, please hit that like button

and subscribe to the channel. There are

more untold stories from Hollywood’s

golden age and beyond that we’re

bringing to light. What do you think

about their relationship? Was her

loyalty admirable or misguided? Let us

know in the comments below. Some loves

are too complicated to work but too

powerful to end. And sometimes the most

important relationships in our lives are

the ones that refuse to fit into any

category we understand. Woody and Diane

proved that, lived it, and left us with

art and questions that will outlast them

News

😱🔥💔 “Before the Final Curtain: Diane Keaton’s Last Words on Al Pacino—The Kiss That Saved Her, The Silence That Broke Her, And The Truth She Hid From Hollywood” 🎭🕯️🌪️

Hollywood loved her for her charm, her wit, and that unforgettable smile. But behind the laughter, Diane Keaton carried secrets…

😱🔥💔 “Before the Curtain Fell: Diane Keaton’s Last Words on Al Pacino — The Kiss She Regretted, The Ring She Never Wore, And The Promise He Couldn’t Keep” 🎭💍🕯️

Hollywood loved her for her charm, her wit, and that unforgettable smile. But behind the laughter, Diane Keaton carried secrets…

😱🔥💔 “Diane Keaton’s Secret Twilight: The Love She Buried, The Name She Whispered Last, And The Illness Hollywood Never Saw Coming” 🕯️🎩🌪️

Hollywood loved her for her charm, her wit, and that unforgettable smile. But behind the laughter, Diane Keaton carried secrets…

😱💔🔥 “The Silence That Broke Hollywood: Diane Keaton’s Last Ultimatum, Al Pacino’s Empty Answer, And The Wordless Goodbye That Still Echoes” 🕯️🎭😶

your friend Merrill. I I love her. Oh, but not but I don’t know. I mean, I don’t see her…

🤯🕯️💔 “Inside Diane Keaton’s Coffin: The Hat That Saved Her, The Dog Who Followed Her to Heaven, And The Father’s Sweater She Refused to Let Go” 🎩🐾🧶

No one realized that only three items were deemed worthy of being placed in Diane Katon’s coffin, and her adopted…

😱🕯️ “Inside Diane Keaton’s Coffin: The Hat, The Dog’s Fur, And Her Father’s Sweater—Three Final Relics, One Devastating Secret Only Her Daughter Could Explain” 💔🎩🐾🧶

No one realized that only three items were deemed worthy of being placed in Diane Katon’s coffin, and her adopted…

End of content

No more pages to load