What’s Inside the Sphinx? 🤯—Forbidden Alloy, Phantom Passages, and the Moment Archaeology Forgot to Breathe ⚡🛕

Under the white fire of the Egyptian sun, the Sphinx is all poise and paradox, a creature that should not move and yet seems to shift each time you look away.

Tourists frame it with their hands; buses exhale diesel into the hot wind; the plateau’s dust paints everything the same pale gold.

The monument’s official story is neat: carved from a single seam of limestone, head to paws a continuous thought in stone, a pharaonic boast frozen in leonine profile.

Neat stories are useful.

They keep the guidebooks slim and the arguments polite.

But neat stories fray where data digs in.

When the first muon tomography maps of the Sphinx’s head flickered to life, the room didn’t erupt.

It recoiled.

Muons don’t care about myths; they pass through stone and betray spaces, density changes, secrets.

The patterns hinted at more than weathering or carving quirks.

There were anomalies—not just voids where the rock ought to be solid, but channels, as if narrow throats had been bored through the skull and down into the body.

Then one return refused to behave: a metallic signature deep in the head, an echo that metal makes when you ping it with the right questions.

The readouts were clinical, but the effect on the team was not.

Someone laughed the way people laugh when they’re afraid.

Someone else sat down, hard, as if gravity had changed its mind.

Metal in a monolith.

A gate where there should be bone.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sphinx-statue-1.jpg)

The word gate did not appear in a single official memo that day.

It arrived whispered at coffee breaks, smuggled into after-hours conversations, trailed by raised eyebrows and the floating ellipses of “we can’t rule it out.

” It shouldn’t be possible, not in a statue carved from bedrock, whose head, body, and paws are—were—supposed to be one continuous block.

But the Sphinx has been shaking “supposed to” loose from its mane for a long time.

Generations have come here and tried to make it confess.

In the 1920s, Emile Baraize carved the monument back out of the sand and found more questions than stone.

He logged voids and tunnels, then watched funds and time run short.

Work closed up, sand fell in, and the Sphinx went back to doing what it does best: waiting.

In the 1970s and 80s, seismographs and ground-penetrating radar took their turn, pricking the earth with questions and getting answers that sounded like hollow.

Every time a scan found a cavity, someone wrote it off as a fissure, a quirk, a natural pocket.

Every time, the legend of hidden chambers shrugged and grew another decade of life.

Then came the age of muons and millimeter-precise radar—tools too stubborn to flatter us with illusions.

They mapped freedoms inside stone, drew the outlines of absence, and, in this latest saga, returned with something metallic humming inside a head carved to face eternity.

This is where the voice of caution clears its throat.

Modern restorations have hurt as often as helped.

Cements shiver under desert breath.

Iron cramps limestone like bad stitches.

What if the hatch is a maintenance relic, installed during some mid-century intervention and half-forgotten under plaster and politics? It’s a theory that naps well until you sit with the scans and see the metallic response is not a ragged patch but a whole, deliberate geometry—a placement too precise, too symmetrical, a rectangle nested where a skull would store its shadows.

And if this is a hatch, why the head? Why not the back, the flank, the paws? Why in the summit of the symbol, the most exposed, the least forgiving.

The answer that fits too well is the one everyone refuses to say out loud.

Legends spoke of a guardian who kept a library of a lost world under lock and stone.

A Hall of Records.

A myth born of longing, dismissed by scholarship, resurrected every few years by a scan that refuses to be ordinary.

The gate—if it is a gate—is where a secret would be safest.

Not in a chest, but in a crown.

Suddenly, the body of the Sphinx is not a statue but a stair.

Those narrow anomalies in the head could be throats—conduits leading down, joining larger cavities mapped decades ago beneath the paws, deep into bedrock where the desert keeps its cold.

A network, not a void.

A design, not an accident.

The mind jumps ahead.

If you open the head, what spills out? Some say treasure, because that’s what people say when they run out of imagination.

Others speak of ritual gear, solar liturgies, the bones of a cult that fused lion strength and royal face into a moonlit machine.

The bolder answer leans toward paper—or whatever the ancients used when stone wasn’t enough.

A record, not of a single dynasty, but of an older story that dynastic Egypt inherited and varnished in gold.

Each theory is a mirror for the person holding it.

Engineers feel the click of cleverness.

Mystics hear the ring of prophecy.

Archaeologists hear career-ending thunder if they back the wrong horse.

The alloy is the part that keeps everyone awake.

The metal signature—still indirect, still filtered through carefully hedged language—doesn’t behave like copper.

It doesn’t shrug like bronze.

It bites back like something closer to steel, a composition ancient Egypt didn’t wield, at least not in the history we currently rehearse.

Is the instrument lying? Calibration errors happen.

Echoes mislead.

The team reran the models until the computers felt warm to the touch.

The signature stayed.

Maybe the gate is younger, a later graft—a 19th or 20th century insertion, a way to reach into the head without chiseling the face.

But then why the secrecy? Why the absence of records? Restoration logs exist like gossip in this discipline; everyone knows everyone’s sins, and yet no one can produce the page that says “installed steel hatch in pharaonic skull, please keep out of guidebooks.

” You see where this goes.

Either the alloy is not what it seems, or our dates are wrong.

Either possibility is dynamite.

This is the point in the story where reasonable people tug on the leash.

Remember Tutankhamun’s phantom doorways? The whispers of Nefertiti waiting behind a painted wall? Radar loves a good optical illusion; plaster can masquerade as a passage; bedrock can pretend to be a door.

It’s all happened before, in headlines that wither into footnotes.

Egyptology is a house haunted by its own hype.

Every time rumors outrun rigor, the discipline has to pay the debt with years of earned skepticism.

That fear is not superstition; it’s survival instinct.

The custodians of the Sphinx weigh risk and memory with quiet hands.

The stone is tired.

Erosion chews.

Pollution salts.

Bad repairs age like lies.

One wrong cut to chase a rumor and the face that launched ten thousand postcards might crumble in the heat.

The paradox is cruel: the only way to know whether the gate is real is the one way that might wound the thing you’re trying to love.

And yet, the Sphinx keeps tugging at its own metaphors.

The head is too loud to ignore.

The old records keep boomeranging back.

Emile Baraize’s notes read like letters from a man who knew he was leaving threads behind.

The Stanford Research Institute’s seismic work drew cavities under the paws that “natural fissures” doesn’t quite domesticate.

Even earlier excavators scratched up tunnels that led to more sand and a stubborn sense that this monument has an inside life it refuses to show in daylight.

Then there are the walls of the enclosure—the stone canyon around the Sphinx’s body, where patterns of erosion track not wind but water, vertical fluting that suggests a climate the Giza plateau hasn’t known since long before dynasties braided crowns.

If rain licked those walls into memory, the Sphinx may be older than the throne most scholars pin to its chest.

Older throws timelines into a centrifuge.

Older means an inheritance we haven’t signed for yet, a debt to a previous cycle of civilizers whose names are gone but whose stone still does math our tools respect.

Speculation blooms like desert flowers after a rare storm.

Advanced acoustics, hydraulic tricks, stone cut so precise the seams behave like ideas.

Pyramids with voids no one expected until the muons drew their rectangular ghosts.

Boxes under Saqqara so big and perfect they hum when you clap.

Walk the Serapeum’s miles of tunnels and stand beside a single-piece granite sarcophagus the size of a minivan, its interior polished to a geometry that makes engineers swear under their breath.

In one off-limits alcove, a box’s corners are so brutally exact that a machinist’s square looks like a compliment.

The lids sit on their lips like silence.

You don’t need aliens to feel small.

You just need a tape measure and the honesty to admit that the past sometimes outruns the present’s pride.

The “gate” in the Sphinx’s head slides into this chorus like a final note that suddenly makes the melody inevitable.

If there’s an entrance, it may not lead to Atlantis; it may lead to paperwork—the kind that rewrites attributions and rearranges museum placards.

Imagine a cache of inscriptions that slide the Sphinx backward by centuries; imagine a ritual architecture whose complexity forces us to treat the Giza plateau as a system, not a scatter of marvels.

Imagine an alloy sample that pins a date we can no longer deny, or that forces metallurgy to admit chapters it has quietly skipped.

Even failure would be productive: if the gate is modern, we’ll learn which restorations altered what, and we’ll document that truth before oral histories flash out like bulbs.

Even a false positive teaches you how to measure better.

But the human drama refuses to be footnoted.

Picture the moment of choice: a conference room that smells faintly of dust and coffee, a projection of the head’s scan frozen mid-frame, the metallic rectangle bright as a heartbeat.

A curator rubs tired eyes.

An engineer taps a finger against a table, calibrating courage.

Someone mentions the tourism economy in a voice meant to sound practical, and it does.

Someone else says “Hall of Records” and everyone pretends not to hear.

The proposal on the table is smaller than the myth: a microboring, a fiber-optic endoscope, a slit so fine the limestone won’t feel it, a promise to withdraw if the first seconds look wrong.

The vote is not about a door.

It’s about whether you can live with not knowing when knowing is within reach.

If you open the head and find a modern hatch, the air will go out of the room but the truth will fill it back in.

If you open it and find an ancient mechanism, the world will lean forward and time will become very loud.

There will be outrage, inevitably—how dare you cut the crown?—and awe, inevitably—how could we not?—and a liminal minute where we realize that the past has a better lawyer than we do.

Then the night shift will get to work.

The fiber-optic eye will creep into a throat of stone.

Dust will move like weather.

The first images will bloom on screens that don’t blink.

If there is a chamber, its air will be older than our ideas about it.

If there are objects, they will not care about our arguments.

If there is nothing, the nothing will be honest and we will have earned it the right way.

Until then, the Sphinx performs its favorite trick: it makes scholars and storytellers use the same verbs.

Guard.

Keep.

Hide.

The head looks east, where the sun rehearses resurrection.

The paws front a temple whose alignments keep smiling at constellations.

Leo rises in the imagination, whether or not the math agrees.

Every detail becomes an omen.

The grain of the limestone.

The proportions of jaw to ruff.

The way restoration scars look like old battles, the way sand returns, patient as a tide.

And beneath it all, the hum of a metal note we can’t stop hearing, a rectangle that sits in the skull like a dare.

We like to say history is carved in stone.

The Sphinx says stone can be revised from the inside.

It says secrets are not failures of transparency but acts of preservation.

It says you don’t bury a library if you plan to leave town forever—you bury it if you intend someone to find it when they are ready.

Maybe that someone is us.

Or maybe we’re the impatient inheritors banging on a vault that was meant to stay closed until our tools learned how not to harm what they love.

There will be no perfect time.

There will only be a better method and a braver consensus.

For now, we live in the charged pause between discovery and decision.

The anomaly in the head refuses to be bullied into geology; the voids under the paws keep echoing back; the alloy hum keeps threading through the data like a taunt.

Egyptology, bruised by past mirages, stands at the threshold of the one rumor that could be real.

The Sphinx will not help.

It will keep its silence.

The head will keep its secrets at sunrise.

The body will keep its water scars like tattoos from another climate.

The tunnels under Saqqara will keep their cold breath and the granite boxes will keep their edges, sharper than our excuses.

The only voice left is ours, in a room where you could hear a pin drop—or a gate unlock.

If we choose to listen before we force, to ask before we cut, to measure three times and enter once, then whatever waits beyond that metallic note will not be lost to our clumsy wonder.

It will be met by a civilization that finally learned to open the past without breaking it.

Until that day, the Sphinx continues to stare past us, toward a horizon it has memorized.

The desert moves.

The city hums.

The tourists squint and shade their phones.

Somewhere in a lab, the scan flickers again, the rectangle bright and undeniable, and for a brief breath the whole field falls quiet, as if the monument itself had just cleared its throat.

News

“Not Just a Tyrant… a Genetic Catastrophe 🤯”—The Secret in Henry VIII’s Bloodline the Palace Never Wanted You to Learn 🕵️♂️🔥

“Not Just a Tyrant… a Genetic Catastrophe 🤯”—The Secret in Henry VIII’s Bloodline the Palace Never Wanted You to Learn…

South India’s Forbidden Pod 🌑—The Day an Earthquake Exposed a Sealed Chamber and a Lingam That Changes Everything

South India’s Forbidden Pod 🌑—The Day an Earthquake Exposed a Sealed Chamber and a Lingam That Changes Everything Start with…

Joystick to the Clouds 😳—WSJ Tests the $190K Personal eVTOL That Flies Itself (Mostly), Tilts Your World, and Redefines Risk 🚁🧠

Joystick to the Clouds 😳—WSJ Tests the $190K Personal eVTOL That Flies Itself (Mostly), Tilts Your World, and Redefines Risk…

Did We Just Catch Life on Camera? 😱—Inside the Jezero Shock, Fuzzy Biosignatures, and the Silence That Froze Mission Control 🛑🔬

Did We Just Catch Life on Camera? 😱—Inside the Jezero Shock, Fuzzy Biosignatures, and the Silence That Froze Mission Control…

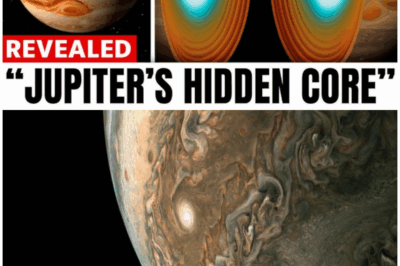

We Finally Saw Jupiter’s Core (And It’s Not Solid) 🚀—The Fuzzy Truth That Rewrites Planet Formation, Shakes Saturn’s Secrets, and Baffles Every Dynamo Model 🧪🌀

We Finally Saw Jupiter’s Core (And It’s Not Solid) 🚀—The Fuzzy Truth That Rewrites Planet Formation, Shakes Saturn’s Secrets, and…

The New Canal? Mexico’s Secret Corridor Project That’s Sending Shockwaves Through World Trade 🌊📦

The New Canal? 🇲🇽 Mexico’s Secret Corridor Project That’s Sending Shockwaves Through World Trade 🌊📦 At first, it sounds impossible—almost…

End of content

No more pages to load