🕵️♂️ Hidden for Decades: The Forbidden Discovery at Hueyatlaco That Suggests Humans Were in the Americas Far Earlier Than We Thought—What Are They Trying to Hide? 🌎

The story of Hueyatlaco begins in the late 1950s when local archaeologist Juan Armenta Camacho made a groundbreaking discovery in the Valsacío basin of Mexico.

While exploring ancient lakebeds, he stumbled upon fossilized animal bones that bore what appeared to be deliberate markings and engravings, hinting at human activity far earlier than the prevailing theories suggested.

This revelation sparked international interest, but as quickly as it gained momentum, the findings began to vanish into obscurity, setting the stage for what would become one of archaeology’s most enduring mysteries.

By the early 1960s, the site became a focal point for a joint Mexican-American research initiative.

Cynthia Irwin Williams, a young American archaeologist, teamed up with Camacho to conduct systematic excavations at Hueyatlaco.

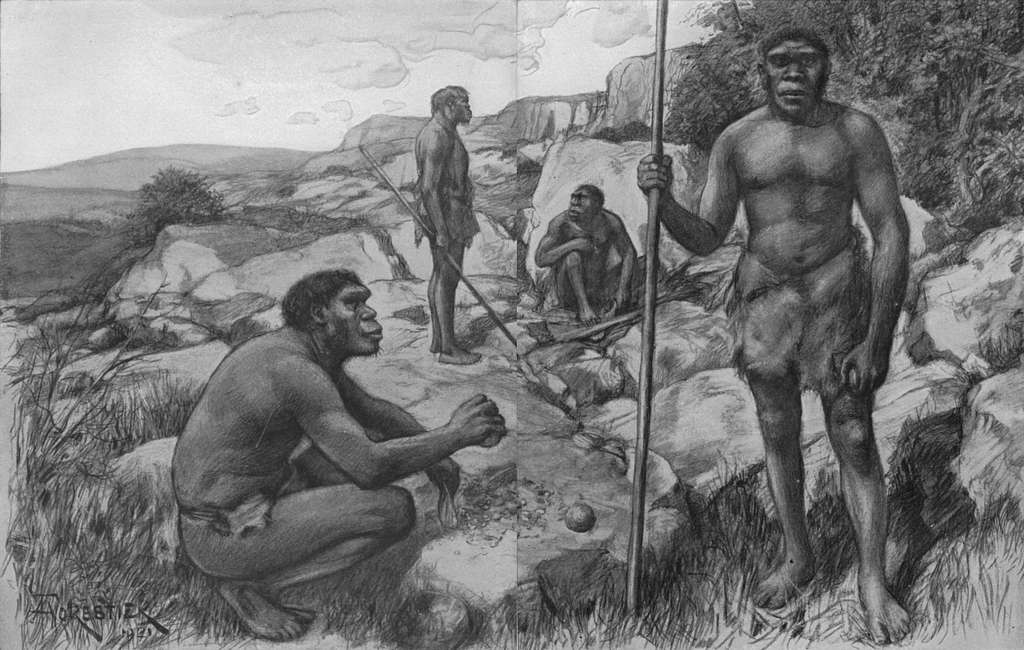

What they found was astonishing: stone tools alongside the fossilized remains of extinct Ice Age animals, with clear cut marks indicating that these creatures had been butchered using primitive implements.

Irwin Williams described the site as a prehistoric kill location where Pleistocene hunters processed their game.

However, dating the site proved to be a formidable challenge.

The bones were fully mineralized, making traditional radiocarbon dating impossible.

Instead, the team turned to geological context, relying on stratigraphic comparisons.

Geologist Hal Mulder estimated that the volcanic ash layer above the artifacts was approximately 22,000 years old, which would imply that the artifacts themselves were even older.

But as discussions emerged about the significance of these findings, the academic community was anything but welcoming.

In the 1960s, the dominant narrative in archaeology was the Clovis-first model, which posited that humans only arrived in the Americas around 13,000 years ago.

To assert that there were human activities dating back 22,000 years—or even further—was to risk professional ostracism.

Controversy erupted almost immediately, culminating in accusations of fraud against the Hueyatlaco team.

A senior Mexican archaeologist alleged that the site had been “salted” with modern tools to create the illusion of age.

Irwin Williams and her colleagues staunchly defended their findings, insisting that every artifact had been found in its original context, embedded within undisturbed layers of sediment.

Despite their efforts, the fallout was swift and severe.

Mexican authorities suspended the excavations, seized Camacho’s artifact collection, and barred him from conducting further fieldwork.

Reports surfaced of armed officials arriving at the site, ordering the research team to cease operations and compelling workers to sign statements claiming the fossils and tools had been planted.

What began as a promising discovery devolved into a bitter controversy that would haunt the field of archaeology for decades.

The dating puzzle persisted, however, and in 1973, Dr.

Virginia Steen McIntyre joined the Huerta Laco project with a mission to determine the site’s true age.

Utilizing multiple independent dating techniques, her team produced shocking results.

Uranium series dating suggested ages between 180,000 and 260,000 years, while zircon fission track dating indicated ages between 260,000 and 370,000 years.

Every method employed converged on the same startling conclusion: the layers at Hueyatlaco were roughly a quarter of a million years old.

In their report, the geologists expressed their awareness of the implications: such a date would significantly expand the timeline of early human presence in the Americas and warranted serious investigation.

Yet, the reaction to these findings was anything but open-minded.

When the extraordinary dates were presented, even Irwin Williams expressed disbelief, insisting that the site must be much younger, despite the lack of geological evidence to support her claim.

This disagreement fractured the research team, with geologists standing by their data while Irwin Williams urged caution.

The ensuing stalemate kept their report unpublished for years, as the inconvenient dates posed a dilemma for the archaeological community.

Steen McIntyre later described encountering extraordinary resistance when attempting to publish the Huerta Laco results.

Manuscripts were delayed, ignored, or outright rejected, with one editor informing her that no mainstream anthropology journal would touch the study because it would “force the rewriting of textbooks.

” Frustrated, she penned a letter in 1981, lamenting the manipulation of scientific thought through the suppression of enigmatic data.

As the years rolled on, the site of Hueyatlaco slipped further into obscurity.

In the 1990s, Steen McIntyre returned to the site only to find that much of the original documentation had vanished.

By 2004, when new investigators reopened a trench, they discovered that the area had been graded flat, effectively erasing the original excavation.

This apparent act of closure left the mystery of Hueyatlaco unresolved, with mainstream archaeologists largely dismissing the 250,000-year-old date as an error.

Yet, crucially, no one has ever disproved the science behind those dates.

The methods applied were sound, and subsequent studies have continued to validate the ancient age of the site.

For instance, micro-paleontologist Sam Van Landingham found fossil diatoms that indicated the deposits formed long before the last Ice Age, supporting the notion that the site could date back hundreds of thousands of years.

Despite the evidence, many skeptics remain.

Critics argue that the stone tools found at Hueyatlaco are too advanced to have been created by any human ancestor from that era.

Paleoarchaeologists contend that the bifacial spear points resemble those made by Homo sapiens, not the more primitive tools one would expect from early hominins.

This circular reasoning assumes what it seeks to prove—that no advanced humans existed in the Americas 250,000 years ago—leading to the dismissal of the evidence rather than an adjustment of the timeline.

The mystery of Hueyatlaco is further complicated by other discoveries that hint at an earlier human presence in the Americas.

In 2005, fossilized footprints allegedly over one million years old were found at the nearby site of Chalnaitouf.

While some researchers argue these impressions were misidentified, the debate continues.

Additionally, the Saruti Mastodon site in California reported evidence of human activity dating back 130,000 years, though critics question the findings.

Perhaps most compelling are the ancient human footprints discovered in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park, which were confirmed to be between 21,000 and 23,000 years old.

These prints provide concrete evidence that humans were present in North America long before the Clovis culture was thought to exist.

As we stand at the crossroads of archaeology and history, the question is no longer whether humans were in the Americas earlier than previously believed, but how much earlier.

Could the findings at Hueyatlaco, along with other controversial evidence, suggest a human narrative that stretches back hundreds of thousands of years?

News

This Massive Door Carved Into a Mountain Doesn’t Open—Could It Be the Key to Unlocking Ancient Secrets of an Advanced Civilization We’ve Yet to Understand? 🤔

🏔️🔍 This Massive Door Carved Into a Mountain Doesn’t Open—Could It Be the Key to Unlocking Ancient Secrets of an…

Before I Die, I Must Tell the Truth: AI Uncovers Shocking Secrets in Da Vinci’s Last Supper That Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew!

🎨🤖 Before I Die, I Must Tell the Truth: AI Uncovers Shocking Secrets in Da Vinci’s Last Supper That Will…

They Scanned 40,000-Year-Old Neanderthal DNA and What They Found Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Human Evolution!

🧬🌍 They Scanned 40,000-Year-Old Neanderthal DNA and What They Found Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Human Evolution!…

The Shocking Revelation of a 40,000-Year-Old Ice Coffin: How One Discovery Could Rewrite Our Understanding of Early Human Culture!

🌌🔍 The Shocking Revelation of a 40,000-Year-Old Ice Coffin: How One Discovery Could Rewrite Our Understanding of Early Human Culture!…

The Mysterious Ancient Handbag: Graham Hancock’s Shocking Theory About a Lost Civilization—Could This Simple Symbol Hold the Key to Our Past?

👜🌍 The Mysterious Ancient Handbag: Graham Hancock’s Shocking Theory About a Lost Civilization—Could This Simple Symbol Hold the Key to…

The Dark Truth of Babylon Revealed: Archaeologists Discover Ominous Artifacts and Signs of Fear Among Ordinary Citizens—What Does This Mean for History?

🏺⚠️ The Dark Truth of Babylon Revealed: Archaeologists Discover Ominous Artifacts and Signs of Fear Among Ordinary Citizens—What Does This…

End of content

No more pages to load