How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

August 17, 1943.

The air at Dobodura airfield in New Guinea shimmered with heat and tension.

Rows of P-38 Lightnings sat lined up under the Pacific sun, their silver wings streaked with grime, fuel, and war fatigue.

Every mechanic, every pilot, knew what the next sortie meant — another chance to survive, or another empty bunk by nightfall.

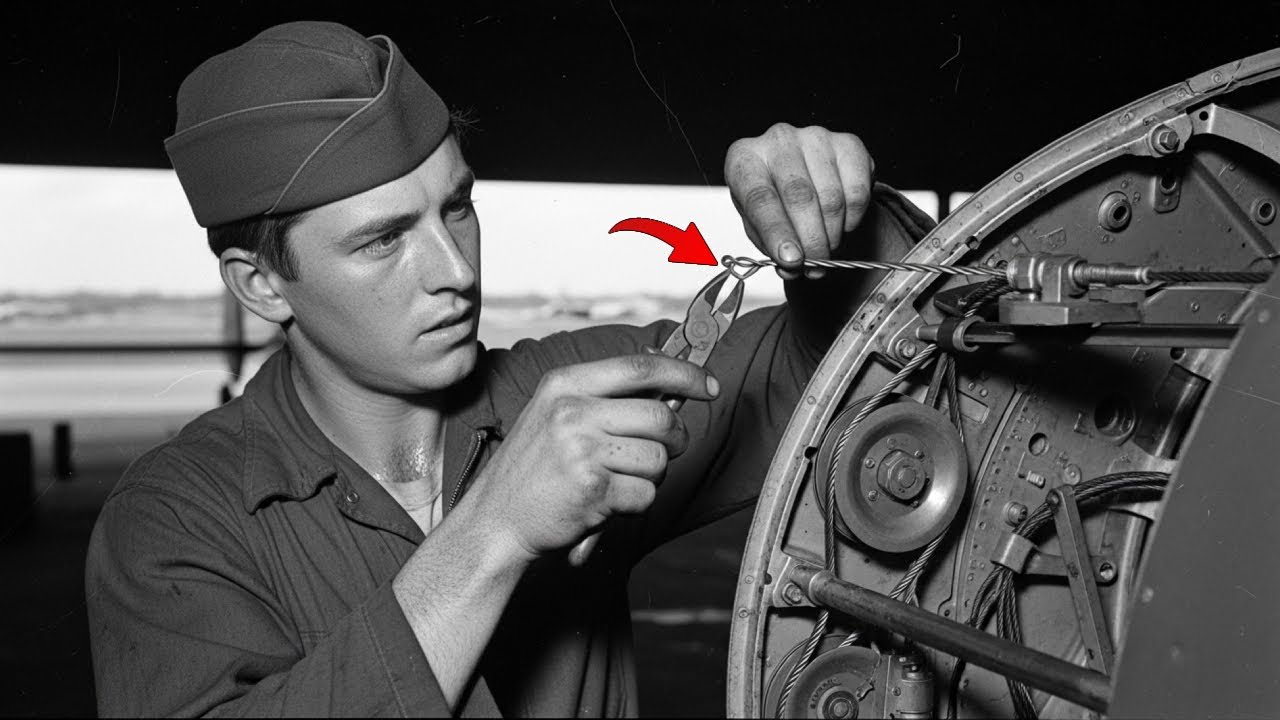

Among them was Technical Sergeant James McKenna, a quiet, meticulous aircraft mechanic who had spent months listening to pilots complain about the same deadly flaw.

The P-38 Lightning, twin-boomed and lightning-fast, was one of America’s most advanced fighters.

It could climb higher and fly faster than the Japanese Zero, but it had one fatal weakness.

It couldn’t turn.

In every dogfight, pilots found themselves struggling against sluggish controls — a split-second lag that meant life or death when facing a Zero’s razor-sharp maneuvers.

They would pull the stick, and the aircraft would hesitate — just a fraction of a second, maybe three-eighths of an inch of slack in the control cables — but in aerial combat, that delay was everything.

That hesitation had already cost too many lives.

McKenna had heard the engineering reports.

He’d seen the specifications, the tables, the Army-approved tolerances.

Everything on paper said the aircraft was fine.

But he knew the paper was wrong.

He watched the control cables vibrate in the tropical humidity, watched how they expanded, loosened, how the stick never felt tight enough.

And as he stood in the maintenance bay that morning, staring at the tangle of wires and pulleys, an idea — half ridiculous, half inspired — began to form in his mind.

He grabbed a scrap of piano wire from the tool bench.

It was thin, flexible, and strong.

He bent it into a Z-shape, hands steady despite the absurdity of what he was about to do.

Then, without authorization, without paperwork, he slipped it into the control linkage of the nearest P-38.

A crude tensioner.

Something no manual had ever suggested — a “stupid” idea, as his crew chief called it.

McKenna just shrugged.

“Let’s see if stupid works,” he said quietly.

That afternoon, Lieutenant Bill Hayes took the modified Lightning up for a test flight.

McKenna stood on the runway, shielding his eyes as the twin engines roared to life.

The aircraft lifted, banked sharply, and then rolled — tighter, smoother, faster than he’d ever seen before.

The response was instant.

The delay was gone.

Hayes came back grinning through the cockpit glass, shouting before the wheels even touched the ground.

“It turns like a damn Zero now!”

Within a week, word spread like wildfire.

Pilots were whispering about a “wire trick” that made their Lightnings dance.

Mechanics began copying McKenna’s modification in secret, cutting scraps of wire from old radios and piano crates, bending them into makeshift tensioners.

There was no order from headquarters.

No memo from Lockheed.

Just one mechanic’s idea spreading from airstrip to airstrip, plane to plane, across the steaming jungles of the Pacific.

And the results were undeniable.

In the following weeks, the kill ratios began to shift.

Where Japanese Zeros once dominated with two kills for every American loss, the numbers were suddenly evening out.

The P-38s could finally dogfight, not just dive and run.

Pilots who had dreaded takeoff now flew with confidence, knowing their aircraft would respond like a living extension of themselves.

By September, at least forty P-38s carried the unauthorized modification, all traced back to McKenna’s bench at Dobodura.

Some engineers protested, calling it unsafe, untested, and in violation of Army Air Force regulations.

But field reports told a different story — missions returning with higher survival rates, pilots describing the controls as “alive.”

It wasn’t until early 1944 that Lockheed engineers, hearing rumors of “impossible improvements,” examined one of the modified planes.

They found the wire, crude and brilliant.

No structural compromise.

Just a perfectly simple solution to a complex mechanical flaw.

By mid-1944, the factory began integrating an improved tension system into the new P-38J model — officially sanctioned, fully tested, and based entirely on McKenna’s field invention.

The Army never issued him a medal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/4c/bb4c5d12-1665-4bb2-8e87-e295ff2f4f7c/top_photo-_donald_mcpherson_us_navy.jpeg)

His name never appeared in reports or design papers.

But among the pilots who flew those missions, who returned home alive because of a six-inch wire, his reputation grew into quiet legend.

“McKenna’s trick,” they called it.

A fix so small it could fit in your pocket — yet powerful enough to change the balance of air combat over the Pacific.

In the years after the war, the lesson lingered in engineering circles: sometimes progress doesn’t come from laboratories or blueprints, but from a pair of hands, a stubborn mind, and a refusal to accept “within tolerance” as good enough.

When historians later traced the evolution of aircraft control systems, they found that the principles first discovered at Dobodura — micro-tension adjustments for precision handling — became standard practice in modern aviation design.

One man, one moment, one wire.

It didn’t just save airplanes.

It saved lives.

And in the chaos of war, where innovation was often born from desperation, James McKenna’s “stupid little wire” stood as a testament to the power of thinking differently — and the courage to act when everyone else was too afraid to try.

News

The American Pilot Searched 40 Years for the Enemy Who Saved Him — Then They Became Brothers

The American Pilot Searched 40 Years for the Enemy Who Saved Him — Then They Became Brothers …

They Called Him Tonto – But What Jay Silverheels Endured Off-Screen Will Leave You Speechless.

They Called Him Tonto – But What Jay Silverheels Endured Off-Screen Will Leave You Speechless. They…

Heartbreaking Confession! Hidden journals and family letters uncover the pain Andy carried to his final days.

Heartbreaking Confession! Hidden journals and family letters uncover the pain Andy carried to his final days. …

“We Finally Know What Really Happened!”…. The Lynyrd Skynyrd mystery has been solved after decades

“We Finally Know What Really Happened!”…. The Lynyrd Skynyrd mystery has been solved after decades For…

NASA COVER-UP EXPOSED! Buzz Aldrin’s emotional confession leaves scientists stunned and the public demanding answers!

NASA COVER-UP EXPOSED! Buzz Aldrin’s emotional confession leaves scientists stunned and the public demanding answers! …

BREAKING NEWS: “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO SEE THIS”…… Scientists Just Scanned Beneath The Sphinx, What They Found Will Terrify The World!

BREAKING NEWS: “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO SEE THIS”…… Scientists Just Scanned Beneath The Sphinx, What They Found Will Terrify…

End of content

No more pages to load