They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that corner of Georgia remembered.

Old men on neighboring porches talked about it for decades: the pewter sky, the pines bowing like sinners, the thunder sitting directly over the roof as if trying to get in.

The big house glowed against all that darkness—lamps burning in every upstairs window, curtains trembling in drafts.

Somewhere behind those yellow panes, the mistress of the place, Eliza Merryweather, clenched her teeth through another contraction and tried not to scream.

Eliza had been raised for composure: soft voice, steady hand.

But breeding is only so strong when your body becomes its own battlefield.

The doctor arrived an hour before the worst rain.

He left his carriage in the drive, handed off the horses to a slave boy, and climbed the steps, wiping his spectacles, sweat already damp at his collar.

It wasn’t his first summons to the Merryweather bedroom, but it was the first time with stakes this high.

“First son,” Mr.

Merryweather had boasted in town two weeks earlier.

“It’s in the blood.

My wife will not disappoint.” Now the man himself was away in Augusta.

When news reached him two days later, the story would already be sealed.

Downstairs, behind the kitchen, another woman labored through the storm.

Ruth, the cook, had caught more babies than most midwives in the county—white and twice as many Black.

She’d seen life take root where it had no right, and watched it be snuffed out for reasons as small as a whispered preference.

This time, the life was inside her own body.

She sat on a rough pallet in the cramped room she shared with two women, sweat slicking her temples, tight curls plastered to her skull, hands clawing at the blanket when the pain came.

Ada, old and unbowed, hummed low and swabbed her brow.

“You know how to do this,” Ada murmured.

“You done helped plenty.

Ain’t no storm going to change that.”

Ruth thought of the night that had brought this child into being—footsteps after midnight, whiskey breath, a door opening without knocking, soft words that were more command than comfort.

She had no need to tell anyone the whole of it.

On a place like this, certain things don’t need to be said.

The house became one immense body—shuddering, breathing, grinding its teeth upstairs and down—white and Black locked into the same painful rhythm.

The thunder answered them.

The rain hammered the panes.

In the front bedroom on the second floor, Eliza clutched carved bedposts until her knuckles went white and veins rose at her wrists.

Her nightgown clung in damp patches.

The doctor bent between her knees, sleeves rolled, glasses askew, hands slick.

“You must push now, Mrs.

Merryweather,” he said.

“I have been pushing,” she hissed.

He did not argue.

He was worried.

The child came slow.

The heartbeat under his stethoscope fluttered like a candle too close to a draft.

When the child finally slid into the world, the storm seemed to break inside the room—a rush of blood and fluid, a soft wet sound.

The doctor wiped and turned; the midwife from town wrapped the baby and held him up.

“Is it a boy?” Eliza asked, but the doctor’s word—“boy”—lacked warmth.

His expression didn’t change.

The midwife didn’t smile.

The thunder cracked so hard that for a moment no one spoke.

“Let me see him,” Eliza said.

The doctor passed the bundle.

The baby’s skin had a bluish pallor; his chest rose and fell shallow and irregular; his cry was thin, more wheeze than sound.

Eliza thought him beautiful anyway for a heartbeat—then the doctor’s hand pressed lightly on the bundle, wanting it back.

“He is alive,” he said, “but weak.” He didn’t finish about the lungs.

“No,” Eliza whispered.

“No, you can treat him.” Her voice climbed.

“He is not dying.

My husband has a son.”

The doctor had seen this before: women clinging to failing infants as if will could hold a soul in place.

He knew better.

He also knew who paid his bills.

“I will do what I can,” he said.

“Rest.

I’ll monitor him.”

From somewhere below, a cry split the house—high, full, angry.

For a second Eliza thought her child had transformed.

Then the sound came again through the floorboards.

The doctor tilted his head.

“Another birthday,” he muttered.

“The cook,” the midwife said.

“Due in a week, I thought.”

The word cook doubled in Eliza’s ears.

The woman in the kitchen, yes—but also the smell of bread, coffee, the house running on a thousand invisible hands.

A piece of property with a life inside her that roared through thunder like that.

The difference between the thin wheeze in Eliza’s arms and the gale downstairs curled cold in Eliza’s belly.

“Healthy lungs,” the midwife chuckled.

Eliza did not.

Her grip tightened; the doctor took the bundle.

“Sleep,” he advised.

“We’ll bring him back when he’s stronger.”

She closed her eyes because she had no choice.

The worst of the storm passed before she woke.

Rain softened to a steady curtain.

Her body felt hollowed by a dull spoon.

The baby wasn’t in the room.

Panic shot her up on her elbows.

“Where is he?”

The door opened.

The doctor entered, solemn.

For a breath, her heart dropped—preparing for mourning.

Then she saw the bundle in his arms.

“This is not—” she began.

The sheet was different.

The baby was different.

Healthy color.

Stronger breathing.

A cry that squawked when jostled.

“Your son,” the doctor said carefully.

“He is stronger now.

We did what we could.”

“You said—he was weak—you said—”

“I was mistaken,” the doctor replied.

“Sometimes nature surprises.”

She took the child.

His weight settled into her arm’s curve.

His cheeks flushed rose.

When she brushed a finger along his jaw, he turned toward it—impatient, alive.

He did not look like the gasping thing she had held.

He looked like her husband, Eliza told herself—there in the set of the brow.

The doctor’s eyes held a question and an answer.

“Do you want my medical opinion,” he asked softly, “or the truth that keeps this house standing?”

Eliza understood and didn’t.

Pain and laudanum made thinking slippery.

She remembered the cry from downstairs; she remembered that strange in-between shade; she remembered that talk could be managed or not.

“Whose child is this?” she asked.

“A woman who has no choice about her body,” he said.

“As is often the case here.”

A strangled sound escaped her.

She looked down: lashes lying like fine brush strokes, a faint cleft at the chin reminiscent of Edward’s stubborn mouth.

“It will show,” she said.

“Someone will see.

There will be talk.”

“There is always talk,” the doctor said.

“About you, your husband, people like Ruth.

This talk can be managed.

The alternative—” He didn’t finish.

Eliza saw it anyway: the funeral, the pity, a cursed womb story, pressure to try again.

“I want to see the other one,” she said abruptly.

Ada carried the kitchen-wrapped bundle upstairs, eyes flat, caution deep in her bones.

The baby’s breaths were shallow; his fists didn’t clench; his limbs lay loose.

He had Edward’s nose.

Eliza’s throat closed.

“Let me see him,” she rasped.

They loosened the blanket—translucent skin, a blue vein at the temple, washed-out irises.

He was hers—worked and bled and screamed out of her—and he was slipping away.

Something in Eliza split.

“You want the truth that keeps this house standing?” she whispered to the doctor without looking away.

“Here it is.

You will write him down as Ruth’s, as you said.

And the other—” she glanced at the healthy child in her arm—“he will be my son.

Do you understand?”

“I have already written it,” the doctor said.

“If you breathe a word,” Eliza replied mildly, “I will say you misrecorded, tried to blackmail us with slander about mixed blood.

I have cousins in Savannah and Augusta.” The iron in her voice shocked even herself.

Ada choked.

“That boy,” she said, pointing at the pale infant.

“He belongs to you in God’s eyes.”

“In God’s eyes,” Eliza snapped.

“This whole place is an abomination.

If God took issue, He should have spoken sooner.”

Ada flinched; the doctor stared at Eliza as if seeing her clearly for the first time.

“You will take him downstairs,” Eliza said.

“Keep him warm.

Do what you can.

When he dies, bury him as you do the others.”

“As a slave baby,” Ada whispered.

“As the ledger says,” Eliza replied.

“We live and die by those books here.”

“He is my husband’s heir,” she added, and looked down at the child who stretched in his sleep—unconcerned.

Thomas Edward Merryweather, they named him.

Years receded; the storm became a scar beneath the sleeve of memory.

Thomas grew tall—trim, exact, watchful.

From the start, people stepped aside when he walked; they mistook restraint for authority.

He was not rude; he was not kind; he moved with a faint remove, as if a guest in his own life.

Ben grew too, downstairs.

In the kitchen they called him Ben because it was easier than the longer name Eliza gasped when she first saw his face in stormlight—Benjamin, after her brother.

In the ledger, he was male infant Ruth, then boy Ruth, then Ben Kitchenhand.

He was narrow-shouldered, coughed in cold weather, and worked like water—quiet, constant, everywhere.

He read in scraps—drawer linings, torn letters, crumpled handbills—sounding out words by stove embers.

Ruth saw and didn’t stop him.

At ten they shared a hallway without sharing a room.

Thomas slept at the front with a view over the oak alley; Ben slept by the back door between stove warmth and drafts.

They crossed on landings, in doorways, in the yard.

Sometimes Thomas threw a ball and let Ben fetch it.

Sometimes he shouted for him to move.

Sometimes, when no one looked, he studied the other boy’s profile and felt something tug.

Other people saw flickers—an aunt from Savannah squinted over coffee: “Fine-featured kitchen lad.

Who’s his father then, Edward?” She laughed.

Silence choked the room.

A neighbor leaned at a hog butchering: “You got one there favors you, Eliza.

Keep that quiet.” Malice glittered in whiskey.

Eliza squeezed her parasol until her knuckles whitened; Ben was sent to the fields for a week.

The ledger never changed.

Ink doesn’t care how faces age.

The first crack came from a dying woman in shadows.

Ada lasted longer than anyone expected.

When the cough took her, it took her fast.

They moved her pallet near the window so she could watch the yard’s light slant.

Ben sat with her; she talked to him like he was older than he was—leaning on his mind, not mocking it.

One afternoon the cough wracked her harder.

“Lightning,” she rasped.

“Two babies crying.

I told God I didn’t want to be there.

He put me in that storm anyway.”

“What storm?” Ben asked.

Ada’s gaze sharpened, seeing two faces laid over each other—double exposure.

“Lord, look at you,” she whispered.

“They grew you right under the same roof and thought nobody would see.”

“Ada, rest.”

“I seen you born,” she insisted, grabbing his wrist.

“I held you, and I held the other, and I watched her decide which you was going to be.”

“Who decided?”

“Find the page,” she whispered.

“Find what he wrote that night.

Then you tell me who you are.”

Ruth tried to wave Ben off as “old woman rambling.” But he had known Ruth long enough to recognize her lie—she stopped looking at him altogether.

He drifted upstairs late afternoon with linens as cover.

Eliza’s study smelled of ink and lavender.

He found the ledger—household accounts, wages, eggs, soap—and near the back, handwriting grew less tidy.

March 30, 1854.

Dr.

Bartlett called at 2 a.m.

Delivery successful.

Male child to be called Thomas Edward Merryweather.

Same night, same storm.

Female slave Ruth delivered of male infant.

Frail, not expected to thrive.

Frail underlined.

A smudge beneath—sun born weak—scrubbed to blur.

Footsteps in the hall.

He slid the ledger shut, fumbling the key.

On the stairs, Thomas appeared.

“What are you doing up here?” Lazy tone; sharp edges.

“Taking linens,” Ben lied.

“Miss Eliza wanted them aired.”

“You’ve been in my mother’s study.” Not a question.

“I was just—”

“What did you touch?”

“Nothing that matters.”

“You don’t decide what matters,” Thomas said.

“You understand?”

“You sure about that?” Ben shot back before he could swallow the words.

They hung between them, astonishing both.

“You ever wonder why folks say I look like your father? You know how many times your mother checks that ledger like ink will change?”

Flush rose at Thomas’s neck.

“If I were you, I’d stop listening to kitchen gossip.

It’ll get you hurt.” He brushed past.

Ben stood gripping linen until his knuckles hurt.

The house shrank and magnified at once—less a cage, more an elaborate lie.

Thomas’s doubts came from another angle.

He’d grown up on expectations—his father tracing property lines, saying “This will all be yours if you don’t shame us.” He learned numbers from ledgers.

He learned Latin, riding, shooting, how to look through a man.

The one lesson he couldn’t master was indifference.

The day his father made him watch a whipping, Thomas copied the men’s posture and felt his vision blur.

He stayed away from the yard on punishment days.

He pretended interest in books.

He noticed how his mother tracked Ben’s movements—not with desire or hate, but with calculation.

He noticed Ruth stiffen when Thomas shared a room with Ben too long.

He noticed in mirror glass that he carried very little of Edward in his face.

When fever swept the county and his father never quite recovered, Thomas found himself in the study with a different ledger—the will.

The lawyer explained clauses and cautions—land passes to you entire, barring scandal.

Manumission possible “at discretion.” Freeing assets imprudent.

Thomas asked about Ruth.

The lawyer said names weren’t listed, but yes—once of age, Thomas could free someone.

It would be “his decision.”

Thomas slept badly.

He did the math: if something had been stolen, he was the one it had been given to.

Ada died with stormlight in her throat.

After, Ben forced the confrontation Ruth had tried to avoid.

“Tell me the truth,” he said in the kitchen at night.

Ruth scrubbed a pot, muscles working under thin fabric.

“About the night I was born,” he said.

“And upstairs.”

The pot clanged.

Ruth sank onto a stool.

For the first time, Ben saw her as once-young, frightened, caught between choices that weren’t choices.

“Miss Eliza’s,” she said finally.

“You took her child’s place.”

“How?”

“The way everything happens here,” she said.

“Somebody with power got scared.

Somebody without power didn’t get to say no.” She told him in halts—storm, doctor, two bundles, Eliza’s market gaze.

She didn’t speak the man who came to Ruth’s bed nine months before.

She didn’t have to.

“You knew,” Ben whispered.

“All this time.”

“I knew,” Ruth said.

“Every day I watched you eat at that table and him at the other and thought there ain’t no good way to fix what they done.

I could have screamed it.

Then what? You think they’d say, ‘Sorry, boy.

Let’s switch you back’? They’d have killed you.

Maybe me.

They’d have sent Thomas to a cousin, changed his name, kept the house.

Truth don’t free people here.

It just changes who gets whipped.”

“So why tell me now?”

“Because you ain’t a boy no more,” Ruth said.

“Because you ain’t ever going to fit.

Better you know exactly why before it breaks you.”

On the fourth day Ben knocked on Eliza’s study door.

She looked up from her ledger.

“Who sent you?”

“No one,” he said, and shut the door.

“You switched us.”

Silence.

The pen rolled, leaving a smear.

“I don’t know what you’re—”

“Ada remembered,” Ben said.

“Ruth told me.

The doctor wrote it down.” He nodded to the ledger.

“You gave him my father.

You sent me to the kitchen.”

“My husband is your master,” Eliza snapped.

“You will not refer to him as—”

“As what he is?” Ben challenged.

“You ought to be grateful,” she said, brittle.

“Do you know what would have become of you otherwise? The son of a—” She cut herself off.

“You would have been another piece of property.

As it is, you have a roof, food, relative kindness.”

“A kindness built on a lie,” Ben said.

“On my life.”

“Do you want an apology?” Eliza demanded suddenly.

“A confession? You want me to fall at your feet?” Rage flared, then drained.

“I did what I thought I had to do,” she said.

“Just like your mother.

Just like everyone here.”

“And now?” Ben asked.

“Now you either keep our secret or you destroy us,” she said.

“That’s the choice this land gives you.”

“What about him?” Ben asked.

“Does Thomas know?”

“He suspects,” Eliza said.

“He has his father’s stubbornness when it comes to prying under floorboards.”

“You ought to tell him,” Ben said.

“And say what?” Eliza asked.

“You’re not my son, but I chose you anyway?”

“Something like that,” Ben said.

“He deserves to hear it from you.”

A knock.

Thomas.

For a beat, all three stared—the mistress behind her desk, the kitchen boy by the window, the heir in the doorway.

“I can come back,” Thomas said.

He would not.

“Shut the door,” Ben said.

Thomas lifted his brows.

Eliza said, “Who gave you the right?” Ben answered, “He did.”

What followed wasn’t neat.

It was halting and overlapping.

Ben spoke first.

“Your mother switched us,” he told Thomas.

“The doctor wrote it.

Ada saw it.

Ruth lived it.”

“Is this true?” Thomas asked.

“Yes,” Eliza said.

The word knocked the air from the room.

“You’re telling me I’ve been living on a name that doesn’t belong,” Thomas said.

“Groomed to take a place that was handed to me like a shirt.

And he—” He couldn’t finish heir.

Ben couldn’t finish father.

“I did not do it lightly,” Eliza said.

“I did it to save what little security I had.

In a world that punishes women for failing to produce sons and never punishes men for taking what isn’t theirs in a woman’s bed.”

“You always blamed Father,” Thomas said.

“Turns out you’re just as willing to bend the world when it suits you.”

“I was trying to survive.”

“So am I,” Thomas said.

“So is he.

So is every soul here.” He looked at Ben.

“What do you want?”

No one had asked Ben that before.

He could have demanded a place at the table, the land, the name.

He said, “A choice.”

“A choice of what?” Eliza asked.

“What I do with what you did,” Ben said.

“Whether I stay and look at your faces, or go try to be someone who isn’t just a line in your ledger.”

“Takes money,” Thomas said.

“Papers.

A white man’s word.”

“You telling me you’ll give me that?” Ben asked.

Thomas looked at his mother.

Eliza’s hands lay flat on ink-stained wood.

She looked very tired.

“If we free him,” she said, “there will be questions.”

“They already do,” Thomas said.

“This way the talk has some truth.” He turned back to Ben.

“There’s no clean freedom for a man like you,” he said.

“You’ll be watched, stopped, asked papers every ten miles.

You might end up back on land like this for a different name.”

“I know,” Ben said.

“I’d rather fail trying than stay knowing.”

“All right,” Thomas said.

“When my father dies—and he will sooner than he thinks—I can manumit without permission.

I’ll put your name there.

I’ll give you enough to reach a city that doesn’t know you.

That’s what I can do.”

“And what will you do with yourself,” Ben asked, “knowing you sit in my place?”

“Live with it,” Thomas said.

“Isn’t that what we do with the sins our parents hand us?” He looked at Eliza.

“We’re not telling Father,” he said.

“He’ll go to his grave believing he had the son he wanted.

That’s the least we can give him.”

“And me?” Eliza asked, voice small.

“You’ll live with the truth,” Thomas said.

“Without anyone else to carry it.”

Edward Merryweather died in November with his son’s name on his lips.

The minister preached property and principle.

Neighbors came in black coats.

Ladies dabbed perfumed handkerchiefs.

Slaves stood in the yard and listened to words that didn’t mention them.

The will passed land to Thomas as expected.

Months later, the courthouse filed manumission papers for one male slave called Ben, formerly of Merryweather Plantation.

Reason: faithful service.

The clerk barely looked before adding it to the stack.

People whispered.

Some said Thomas had gone soft.

Some said he was scheming to rent Ben out.

Some said guilt.

No one said perhaps he freed his brother.

Ben left before sunrise on a muggy spring morning.

Ruth packed cornbread, smoked meat, a thrice-mended shirt.

Thomas handed him coins and an envelope of papers.

Eliza did not come down.

She watched from the upstairs window, a hand at her mouth.

Ben did not look back until the bend in the oak alley gave him a clear view.

The house sat in soft gold light, windows reflecting sky, white columns catching sun.

Solid, respectable—the kind of house people pointed to for good breeding and God’s favor.

He knew now it was built as much on ink as brick—on names written and erased, on lives recorded as property, on a single night in 1854 when a storm gave a woman a choice and she chose herself.

He touched the envelope.

Freedom was written there in language he couldn’t have imagined—fragile, contingent, dependent on white men recognizing other white men’s signatures.

It could save him or fail him depending on who read it and how they felt that day.

He set his face toward the road.

The loudest scandals end in blood.

The ones that never quite break the surface—those rot a family from the inside out.

If stories like this make you sit up a little straighter, and you want more buried ledgers and whispered choices brought into the light, say so.

Some quiet scandals need someone around to hear them.

News

The Mistress Who Promised Freedom To The Slave Who Impregnated Her First—She Lied Twice

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more…

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

The 7’4 Slave Giant Who Broke 11 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 22

They say it was the sound that damned him. Not the height—though he stood a full head above any man…

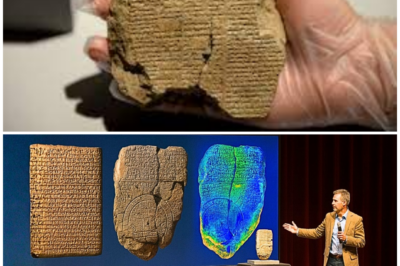

🔥 “They Wrote About Something That Shouldn’t Have Existed Yet…”: Newly Unearthed Sumerian Records Shock the World With Alleged Descriptions of Technology, Sky-Beings, and Events Thousands of Years Ahead of Their Time—A Revelation So Disruptive It Threatens to Rewrite Humanity’s Origin Story and Challenge Every Assumption We Thought Was Untouchable 😱

From the moment archaeologists pried the first cuneiform tablets out of the dust of southern Iraq in the late 1800s,…

🔥 “The Numbers Didn’t Make Sense… Then They Got Worse”: In a Fictionalized Cosmic Exposé, Avi Loeb Reveals He Found Something Terrifying in 3I/ATLAS’s Jet Measurements—Anomalies So Violent, Precise, and Unnatural That NASA’s Silence Only Deepens the Suspicion That This Object Is Not Behaving Like a Comet but Like a Machine Awakening in the Dark 😱

As scientists continue to scrutinize the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS, a growing body of data is revealing patterns that defy conventional…

🔥 “It Sent a Signal We Weren’t Meant to Decode…”: Panic Sweeps Through the Scientific Underground After Michio Kaku Warns That 3I/ATLAS Has ‘Activated Something Beyond Our Understanding,’ Triggering A Frenzy of Theories Ranging From Exotic Physics to a Silent Cosmic Beacon That Could Change Our Place in the Universe Forever 😱

When will the universe reveal its next stunning secret? For theoretical physicists and sky-watchers alike, that moment is happening right…

End of content

No more pages to load