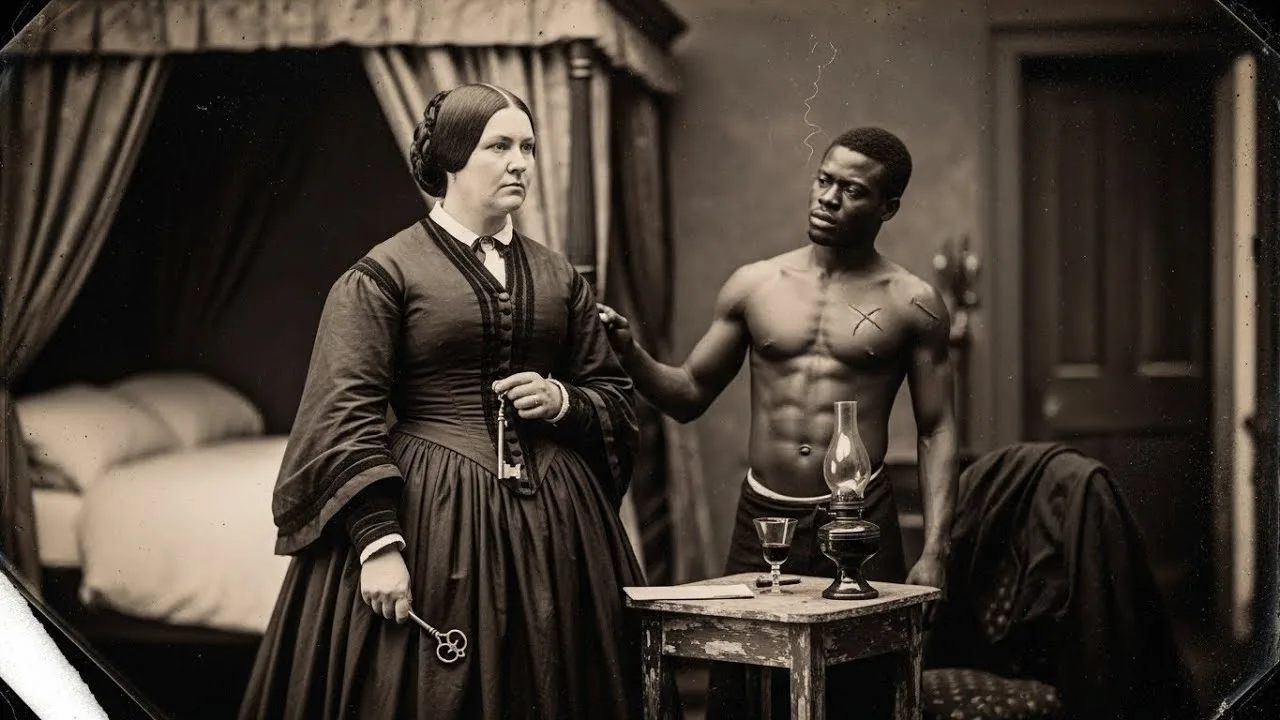

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more dangerous than cotton weights and purchased debts.

Summer heat pressed against the county archives like a hand.

The ceiling fan clicked and wobbled overhead while I turned the pages of the Fairchance Plantation book—columns of bales and dates, tally marks and names of hands—until my eye snagged on something that didn’t belong.

Between two neat streams of numbers, tight script cut through the order:

I promised him freedom twice.

Once for each child I asked of his body.

I lied both times.

H.

Ward.

The ink looked fresher than the century would allow.

Along the margin, rescued from silence by a different hand—angled, firm, written with someone else’s anger—another line:

Let this stand as the only freedom I ever got from her.

These words.

The ledger called him simply Josiah.

So this is his story as much as hers, living in the cracks between numbers, the margins of a book designed to deny him humanity.

If you listen closely, you can hear it on nights when the air grows thick as breath from a long-dead throat.

Fairchance lay a few miles outside town when the town was smaller, meaner, and more proud of its brutality.

From the road, the house rose white and wide, columns like teeth biting the porch, windows dark as closed eyelids.

Magnolias flanked the drive, roots pushing like something trying to surface.

Beyond, the fields spread in a white sea under a hot sky, waiting for hands that did not own themselves.

Josiah was born in those quarters.

He counted life against seasons: the year the well went dry; the year fever came; the year they narrowed rations; the year the overseer fell from his horse; the year Helena Ward arrived with two trunks and a face that didn’t yet know how to lie the way it needed to.

By twenty-four he had a whip scar across his left shoulder, a wife in another cabin, and a little girl who toddled the red clay road barefoot without stumbling.

He was tall and stronger than most—white men appraised him like livestock—and he had stolen a handful of letters the way some steal bread: quiet, patient, one forbidden crumb at a time.

A scrap of newspaper here.

A torn corner of Bible there.

An older woman tracing shapes in hearth soot.

He didn’t think of himself as smart.

He thought of himself as hungry.

Helena thought of him as something else.

She’d been on that land eight years when she sent for him on business that wasn’t hauling casks or fixing shutters.

The mirror told her a story each morning now: faint lines at her eyes, a mouth held too tight, a waist that had not yet swelled with proof God smiled upon her.

In town, women wrapped pity in scripture and thin smiles—poor Mrs.

Ward, three years and no heir.

Her husband, Charles Ward, had inherited land and a name and not much else.

He drank more than he should.

The plantations—two, technically—were leveraged and webbed in debt he pretended not to see.

The place needed a son to secure its legacy, another white Ward to inherit the soil and the bodies bound to it.

Helena needed something more than a son: proof that God had not turned his face from her.

The doctor in town was careful, the way men are careful when telling uncomfortable truths to those who pay them.

The problem, he implied, did not sit with her.

He wrapped it in “constitutions” and “delicate matters,” but Helena heard what he wouldn’t say aloud: Charles Ward’s body had failed him in a way a gentleman did not confess.

She went home and stared at the cold fireplace until the light shifted.

Then she looked out the window and saw Josiah leading the mule cart from the far field, shirt on his shoulder, sweat shining at his neck.

A little girl sat on the cart’s edge—his daughter—hair in tight braids, clapping at every jolt.

When the mule stumbled, he steadied the animal with one hand and the child with the other, gentle as if both were equally precious.

Something clenched inside Helena.

Not desire—not yet—not exactly.

It was envy, raw and ugly and heavy as iron.

That night, beside her snoring husband, she whispered a prayer that was more bargain than plea.

God, if you will not give me what is mine by marriage, then show me another way.

A week later, she sent for Josiah.

The back veranda.

Then the cool gloom he’d only ever crossed delivering wood or trunks, never to the good sitting room.

The air smelled of rosewater and old smoke.

She sat by the window, pale light picking the fine lines of her profile.

Cream dress, high collar, hair smoothed into a coil that did not move when she turned.

“Josiah,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“How long have you been at Fairchance?”

“All my life, ma’am.”

“Your parents?”

“Mama died when I was a boy.

Daddy was sold off.

Long time ago.”

“And you have a wife.

And a child.”

“Yes, ma’am.

My wife is Lotty.

My little girl is Ruth.”

The names sat in the air like uninvited guests.

“She looks strong,” Helena murmured.

“Healthy.

You have another?”

“Not yet, ma’am.

Just Ruth.”

Just, she repeated softly, and made him wish he could take the word back.

She crossed the room and, without asking, touched his shoulder.

Not a blow.

Not a command.

An inspection.

Her fingers traced the muscle as if testing meat at the market.

She gathered herself, the tremor still there, now hidden in her skirts.

“I asked you here,” she said, “because I have a matter of trust to discuss.”

Silence was safer than the wrong words.

“You know Mr.

Ward and I have no children.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“You also know the future of this place depends on an heir.”

He watched her pace the mantel like someone walking a cliff edge.

“If I told you there might be a way to earn your freedom,” she asked, “would you listen?”

Freedom hung in the air like a language he’d only ever heard in dreams.

“My freedom, ma’am?”

“Yes.”

His heart kicked his ribs.

“How?”

“By doing for me what my husband cannot.”

The floor tilted.

His mind understood; his body understood.

His soul refused.

“I don’t understand, ma’am,” he said, though he did.

“I want a child,” she said.

“A child who will carry Mr.

Ward’s name and inherit this place.

I have prayed until my knees ached.

The doctor says my body can do what is required.

It is my husband’s constitution that fails us.

If you were to lie with me in secret until I conceived, if a child came of it, I would sign manumission papers.

Mr.

Tyler, our lawyer, will witness them.

You would be free.”

“Just me,” he said, the tongue thick.

Her jaw tightened.

“I cannot promise more.

The law is a tangle.

A woman cannot simply free a man’s property without his consent.

But I can work.

I can persuade.

If you give me a son, I will give you your freedom.

That is the bargain.”

He thought of Lotty bent over the wash tubs, steam rising around her.

He thought of Ruth climbing into his lap, smelling of smoke and hope.

He thought of the older men’s stories: cities with no whips, places where a black man’s hands belonged to him.

A cold rage rose that his body was the coin offered.

“If I say no?” he asked.

“If you say no,” Helena said, something hard sliding into place, “nothing changes.

You go back to the fields.

You watch your daughter grow up here.

You grow old and die; your grandchildren pick cotton in your rows.

If you say yes, you have a chance.” She lifted a small leather Bible, laid fingers on the thin page.

“I swear it.”

He glanced toward the window and the rows beyond.

“May I speak plain, ma’am?”

Her brows rose.

“Plain enough.”

“If I’m free,” he said slowly, “I won’t leave alone.

I have a wife and daughter.

They belong to this place on paper.

If I go and they stay, what kind of freedom is that?”

“You ask too much.”

“I ask nothing yet.

You offer.”

“I cannot promise what I do not own,” she said.

“Your wife and child are Mr.

Ward’s property.

But if I have a son, men soften.

I could press him then.

Don’t ask me for the world when all I can reach is a door cracked open.

Say yes, Josiah.

Step toward it.”

There were no good answers, only ones that broke different parts of him.

“I will do what you ask, ma’am,” he said.

Her shoulders dropped—relief, triumph, both.

“Come after dark,” she said.

“Side door by the music room.”

The first night, he vomited in the hedges before he went inside.

Guests had gone.

Mr.

Ward had lumbered upstairs.

Helena opened the side door herself, hair unbound, younger and more dangerous without pins.

“Come,” she said.

What passed between them belonged to transaction and calculation, not romance.

He did not kiss her.

She didn’t ask him to.

It was deliberate and mechanical—using his body like a syringe to inject the future.

After, she lay with a hand on her flat stomach and whispered, “God will know why I did this.”

He went home and lay beside Lotty, who moved into him in her sleep as she always did.

He couldn’t sleep.

His heartbeat hammered out a new sentence, length unknown.

The months that followed were measured in missed cycles and morning sickness.

Helena kept a secret ledger inside her Bible now.

When her bleeding failed to come, she held the book tighter.

When she retched at dawn, she pressed a trembling hand to her abdomen and whispered thank you.

The doctor confirmed it.

Word spread.

In the quarters, old women shook their heads and muttered.

In town, ladies bought small bonnets just in case and pretended they hadn’t.

Josiah heard it from a fellow hand, delivered with a sideways glance.

“They say Miss Helena got a baby coming,” the man said.

“God works mysterious.”

“Mysterious,” Josiah said, tasting bitterness.

Helena sent for him less often.

When she did, her touches lingered.

“God used you as His instrument,” she told him, hand on her swelling belly.

“Remember what I promised.”

“My wife,” he said, the words slipping out like blood.

“I told you I cannot promise what isn’t mine,” she snapped.

“I am carrying your chance.

Do not make me regret it.”

Lotty noticed the nights, the silence, the flinch at her hand.

“Where you been?” she asked, voice quiet in the dark.

“Working.”

“Houses don’t break that much.”

“There are things I can’t say.

Not safe.”

“Safe for who?” she asked.

“For you? For me? For her?” She lay still a long while.

“Whatever you doing up there,” she said, “it’s cutting all of us.”

“I ain’t forgotten,” he said.

“I just don’t see another way.”

The labor began under a bruised sky.

Lightning flickered.

Inside, the doctor worked and Mammy—who’d ushered more births than any physician—commanded with steady hands.

Josiah stood under the porch edge, soaked by wind-driven rain, listening to Helena scream.

He had never heard a white woman sound like that.

Dawn delivered a thin wail.

Mammy stepped out later, wiping her hands.

“Baby’s born,” she said.

“Got all his fingers and toes.”

“Boy or girl?” Josiah asked.

“Boy,” she said.

“Just what the missus wanted.” Then, softer: “Listen to me, child.

That woman bound you tighter than any chain.

Keep your mind sharp.

Don’t let her words muddle it.”

“I have her promise,” Josiah said, clinging to it like driftwood.

“She swore on her Bible.”

Mammy snorted.

“White folks swear on books they own like land.

They forget the words were written for everybody.”

Helena named the boy Charles.

His skin was lighter than Josiah feared, darker than the elder Ward expected.

The father laughed it off—“Olive complexion from my mother’s people”—and money smoothed doubt.

Six weeks later Helena summoned Josiah.

She had the child at her breast.

“This,” she said, half pride, half warning, “is the fruit of our bargain.

He is yours.

He is mine.

The world will say he is Mr.

Ward’s.

That is how it must be.”

“My papers,” Josiah said.

“I spoke to Mr.

Tyler,” she replied.

“They’re drafted.

Await my signature.

But we must be cautious.

If Mr.

Ward sees a man freed so soon, he will ask questions.

Men in this county will investigate.

Timing matters.

Give it a year, perhaps two.

Then I will sign.”

It was the first lie.

She might have believed it while she said it.

Possession had rooted in her during sleepless nights—of the child, the land, and the man whose blood ran in both.

To free Josiah now would loosen her grip.

She craved control the way other women craved jewels.

“Be content,” she told him.

“Your son will be raised as a gentleman.”

“He won’t call me that,” Josiah said.

“He will call you what the world says you are,” Helena replied.

“But I will know and God will know.”

“You keep speaking of God,” he said.

“I never yet seen Him sign a paper.”

Years bent.

Charles toddled on French rugs, ran the hallway with a wooden soldier, learned to read the begats from Helena’s finger.

Ruth learned to carry water and sweep floors as soon as she could lift a bucket.

She learned letters by watching her father scratch J O S I A H in dirt.

Sometimes, when no one noticed, Charles peered from the upstairs window at the fields and watched the dark figures moving.

He saw a tall man among them and felt a pull he could not name.

“Stay away from the quarters,” Helena told him.

“They are not your concern.”

“Why does that man look like me?” he blurted once.

“He does not,” she snapped.

“You are a Ward.

They are not.”

At night, Ruth asked, “Why he get to ride the pony?” Josiah said, “Because that’s his place.” “What’s ours?” “Here,” he said, gesturing to four walls.

Then, after a breath: “But maybe not always.”

Mr.

Ward’s cough grew to a tearing bark.

Rumors of debt stopped being whispers.

In the study, Helena told Mr.

Tyler, “We must protect my son’s inheritance.” “The people too,” she added, the word doing somersaults to find a shape like humanity.

“Assets,” Mr.

Tyler said.

“They will belong to the boy.”

The second bargain began on a day when the sun felt too close to the earth.

Nearly five years had passed.

Mr.

Ward moved slower.

He drank more.

He raged when whiskey mingled with fear.

Helena stood at the foot of their bed and measured the thin rise and fall of his chest.

One heir is not enough, she calculated.

One heir and one spare.

She summoned Josiah to the music room—an unused space where the piano gathered dust.

“You sent for me,” he said.

“Yes.” Her hands were clasped white.

“I want another child.

Another boy if God will grant it.”

“You’re asking the same thing.”

“Yes,” she said, “but with more to offer.” She pulled a folded bundle from a drawer.

“Manumission documents for you, Lotty, and Ruth.

Mr.

Tyler drew them up.

I have not signed.”

“You could sign now,” he said.

“I could,” she said.

“And get nothing in return but a more complicated life.

Better to cut the thread clean once I’m secure.”

“You are using us,” he said.

“The world has used me as well,” she said.

“As a womb to be judged, as a body to be blamed.

I am bargaining with what I have.”

“And what I have,” he said, “is my body.”

“Your body,” she replied, “and your seed.” The word turned dirty in her mouth, half scripture, half secret.

“If I agree,” he said, “and you lie again—don’t bring God into it.

There ain’t a prayer that washes that clean.”

“Will you do it?” she asked.

He wanted to say no.

He also wanted to watch Ruth walk a street where no one could raise a hand to her.

“I will,” he said.

“But this is the last time.

If you break your word, you will answer for it here, if not in heaven.”

The second pregnancy did not go as smoothly as the first.

Helena was older.

Her body did not bend so easily.

She was sicker.

Her ankles swelled.

Her moods cut like broken glass.

She summoned him not for intimacy but for conversation, as if he could anchor her fear.

“Do you ever wonder what you’ll do when you’re free?” she asked.

“All the time.”

“Where will you go?”

“North.

Maybe farther.

Anywhere the law don’t own me.”

“What will you do?”

“Work,” he said.

“Same as I always have.

Just with my own hands under my own command.”

“I cannot imagine doing anything without permission,” she murmured.

“You own me,” he said.

“My wife.

My child.

The ground.

That not permission?”

“Everything is Mr.

Ward’s,” she insisted, the words ringing hollow.

“Even my body was in the marriage contract.”

“You’re the one making bargains,” he said.

“Paper says one thing.

Your choices say another.”

She flinched.

“You think I do this for pleasure?”

“I think you do it because you can, and nobody taught you how not to.”

“Get out,” she said, tears bright.

“Before I forget why I ever thought you worth saving.”

The labor was longer.

Harder.

Helena screamed until her voice broke.

Sheets soaked through.

The doctor’s face pinched.

Mammy’s hands stayed steady.

At dawn the child came with a wet gasp.

“A girl,” Mammy said.

Alive.

Whole.

The head misshapen from the long labor.

Breath ragged.

Helena reached, half-conscious.

“Is she—”

“Here,” Mammy said.

“That’s what matters.”

The baby’s skin was darker than Charles’s.

Her nose was Josiah’s again.

Helena wept for pain and relief and terror, and because the world ate girls alive.

They named her Eliza.

At three weeks she sickened.

Breath rattled, skin flushed then waxed.

She died in the night, wrapped in linen too fine ever to have touched dirt.

They buried her under a cedar.

No marker.

Helena could not carve a date in stone.

Something hardened in Helena after.

Fever hovered.

Some nights she raved, calling Josiah’s name and cursing him in the same breath.

On a fever night, little Charles crept to her bed and heard her whisper, “I promised you.

Promised you twice.

Twice I lied.” He did not understand, but the words lodged like burrs.

With Eliza’s death, Helena built a theology she could live with: God had rejected the second bargain; therefore, He absolved her of the promise.

The manumission papers curled in the drawer, edges soft from humidity.

One morning Josiah came to the porch.

“Ma’am,” he said.

“I did not send for you,” she replied.

“No, ma’am,” he said, “but we got unfinished business.” His voice was too steady.

“This is not the time.”

“It’s been years of not-the-time,” he said.

“You promised my freedom twice.

You promised my wife’s.

My daughter’s.

You got your boy in the house.

You had your second child.” He swallowed.

“You buried her.

I grieve too.

That don’t erase your words.”

“Do you think,” she snapped, “I can march into town while the ground is fresh on my daughter’s grave and ask Mr.

Tyler to notarize papers freeing a man who—” She cut herself off.

“A man who what?” he asked, stepping closer, hands shaking at his sides.

“Who you used? Who gave you children you claim out loud and a child you bury in silence?”

“Be careful,” she hissed.

“You tread ground that can swallow you whole.”

“I been standing on that ground my whole life,” he said.

“Difference now is I got your words in my ears.”

“Words are wind,” she said.

“Circumstances change.

God took my child.

He weakened my husband.

He changed the balance.”

“God didn’t write those papers and tuck them in your drawer,” Josiah said.

“You did.

God didn’t ask me into your bed.

You did.

Don’t put this on Him.”

“Get back to work,” she said.

“Before I have Ezra put you in the stocks for insolence.”

“That your answer?”

“That is my answer.”

“You said you’d free me once,” he said.

“Then you said you’d free all of us.

That’s twice you broke your word.”

“Go,” she whispered.

He went—because the house watched, because the overseer watched, because he could feel even the boy’s eyes at the upstairs window.

After that day, something in Josiah snapped—not all at once, but like rot working through a beam until the weight it carried became too much.

He worked.

He ate.

He slept.

He listened.

Whispers had always lived between the white folks: Helena’s seclusion; the boy whose face didn’t quite fit; Josiah’s late-night errands.

Men in that county were practiced at telling themselves stories that made them comfortable.

But rot smells.

One humid afternoon, little Charles wandered the house while Helena slept in a chair.

In the study he climbed into the leather chair and found the ledger open.

He could read more now.

Bales.

Dates.

Names.

Along the margin: I promised him freedom twice.

He mouthed the words until Ezra’s voice cut the air.

“You ain’t to touch that book,” the overseer said.

He snapped it shut and shooed the boy.

That night Charles asked, “Mama, did you promise someone freedom? Did you lie?” She told him grown folks make promises they mean but cannot keep.

“Like when God took Eliza?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“But you always say God don’t break promises,” he said.

“So if He don’t and you do, don’t that make you worse?”

The question, asked without malice, cut deeper than any accusation.

The breaking point came when Mr.

Ward, drunker than usual, staggered onto the porch and spotted Josiah.

“You’re a tall one,” he slurred.

“Good breeding stock, ain’t that right, Ezra?” He squinted.

“Funny thing—that boy of mine’s got your height.

Your shoulders.

Folks say he’s got his mother’s eyes.

I ain’t sure.” He laughed without humor.

“You ain’t been sniffing around where you got no right?” he asked Josiah.

“No, sir,” Josiah said.

“I do what I’m told.”

Later that day, Mr.

Ward paused at the edge of the yard to glare at Ruth struggling with a bucket too big for her frame.

“Keep her away from the house,” he muttered.

“Too many eyes like that around here already.”

Those words reached Josiah.

Ice went down his spine.

Mr.

Ward died with a cough in his lungs and doubts he never named.

Helena wore black and a veil and the stiff mask of grief.

Men came with papers.

Creditors circled.

Parcels were peeled away like skin.

When the dust settled, Fairchance remained—smaller, but the boy Charles stood as its young master.

Helena signed deeds, notices, receipts.

The manumission papers stayed in the drawer.

Josiah waited.

The summons didn’t come.

He knocked on the side door himself.

Helena opened it, surprise flickering, composure hardening.

“I’ve been waiting,” he said.

“I waited while he died.

While you buried him.

While you signed papers to keep this place.

Now you got the power, just like you said.

Power to keep your boy safe.

Power to free the man you used and the family you held hostage.

What you going to do with it, Helena?”

He’d never said her first name.

It startled them both.

“You will address me as Mrs.

Ward,” she said.

“Not today.”

“I cannot free you,” she said finally.

“Not now.

Creditors watch every move.

If I let property go, they’ll say I’m unfit.

They’ll come for the rest.”

“You got a hundred souls here,” he said.

“You could free one family and they’d praise you in town.

This ain’t about them.

It ain’t even about your boy.

It’s about you not wanting to let go.

Of me.

Of what you done.”

“You don’t know what you’re saying,” she said, but the force had drained.

Tears rose.

“If I free you, I will see you everywhere—town, church, road.

I will see the truth of what I did in a body I cannot command.

I cannot bear that.”

“There it is,” he said softly.

“You finally said it.”

“You lied twice to me,” he said.

“But the worst lie you tell is the one you tell yourself—that you ain’t a monster.”

She slapped him.

The sound cracked the hall.

They froze.

A smaller figure appeared at the stairs.

“Mama?” Charles whispered.

“Nothing,” Helena said.

“Go back upstairs.”

“Did he hurt you?” Charles asked.

“No,” Josiah said.

“Your mama just reminding me of my place.”

Charles looked between them, and something clicked—the angle of the cheek, the mirror-matching eyes.

“You look like him,” he whispered.

“Go upstairs,” Helena repeated, voice sharp.

He fled.

“I ain’t asking anymore,” Josiah said quietly.

“You had your chances.

There won’t be a third.”

“You have nowhere to go,” she said.

“You’ll be hunted.

Caught.

Killed.”

“Maybe,” he said.

“Maybe not.

Either way, it’ll be my choice.

Not yours.”

He stepped backward into the yard.

“Keep your papers,” he said.

“Keep your land.

Keep your lies.

You don’t own my hope no more.”

He turned and walked away.

What happened next never made it into county records.

There were no notices, no ads in distant papers.

Whispers thickened among the quarters: a path north; a cousin who’d made Ohio; a preacher whose scripture slanted toward escape.

One humid night, Ruth woke to her father’s silhouette in moon-cracked light.

“Pack light,” he whispered.

“Just what you can carry quiet.

We leaving.”

Lotty stared.

“You sure?”

“I ain’t sure nothing,” he said.

“’Cept staying is dying slow.

I’d rather risk a quick end on the road than watch her break her promise a third time.”

“Where we going?” Ruth asked.

“Someplace nobody owns your name.”

They slipped through a gap in the fence Josiah had measured in his mind a thousand times.

The stars were indifferent.

They were gone by dawn.

Helena heard at midmorning.

“Josiah’s missing,” Ezra said.

“His woman and girl, too.”

“Send riders,” she said.

They searched three days.

No sign past the old ferry crossing.

“They got help,” Ezra said.

“We can run ads.”

“No,” Helena snapped.

Then, forcing calm: “Let them go.”

When Ezra left, she opened the drawer and took out the manumission papers.

She considered signing them and burning them—a private penance.

Instead, she tore them into strips and fed them to the fire.

The flames curled ink and parchment into black shell.

“Be free, then,” she whispered to smoke.

“But keep your distance.”

She opened the ledger and saw her confession in the margin.

She did not scratch it out.

She closed the book and walked away.

Years later, after Helena was buried under the cedar beside the child she lost, the ledger drifted with other papers—deeds, births, deaths, bills of sale—into the county archives.

No one cared about the scribbles in the margins.

They mattered to nobody’s inheritance.

But paper outlives breath.

Sitting in the dim reading room generations later, I traced ink with a finger and felt Josiah’s voice step out of the chains Helena tried to keep it in.

His handwriting, likely added in a stolen moment with hands still rough from fields, had answered her confession:

Let this stand as the only freedom I ever got from her.

These words.

I sat back and listened to the fan, to distant footsteps, to ghosts rustling in stacked boxes.

If you’ve come this far—through bargains and births, burials and breaks—you are part of that freedom, too.

Stories like Josiah’s were never meant to be read aloud.

That’s why they matter.

What stays with me isn’t only Helena’s bargains or Josiah’s choice.

It’s the children caught between—the boy who looked out a window and recognized his face in a field, the girl who learned to carve her father’s name into dirt.

And a line scrawled in a margin—ink that refused to be owned.

News

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

The 7’4 Slave Giant Who Broke 11 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 22

They say it was the sound that damned him. Not the height—though he stood a full head above any man…

🔥 “They Wrote About Something That Shouldn’t Have Existed Yet…”: Newly Unearthed Sumerian Records Shock the World With Alleged Descriptions of Technology, Sky-Beings, and Events Thousands of Years Ahead of Their Time—A Revelation So Disruptive It Threatens to Rewrite Humanity’s Origin Story and Challenge Every Assumption We Thought Was Untouchable 😱

From the moment archaeologists pried the first cuneiform tablets out of the dust of southern Iraq in the late 1800s,…

🔥 “The Numbers Didn’t Make Sense… Then They Got Worse”: In a Fictionalized Cosmic Exposé, Avi Loeb Reveals He Found Something Terrifying in 3I/ATLAS’s Jet Measurements—Anomalies So Violent, Precise, and Unnatural That NASA’s Silence Only Deepens the Suspicion That This Object Is Not Behaving Like a Comet but Like a Machine Awakening in the Dark 😱

As scientists continue to scrutinize the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS, a growing body of data is revealing patterns that defy conventional…

🔥 “It Sent a Signal We Weren’t Meant to Decode…”: Panic Sweeps Through the Scientific Underground After Michio Kaku Warns That 3I/ATLAS Has ‘Activated Something Beyond Our Understanding,’ Triggering A Frenzy of Theories Ranging From Exotic Physics to a Silent Cosmic Beacon That Could Change Our Place in the Universe Forever 😱

When will the universe reveal its next stunning secret? For theoretical physicists and sky-watchers alike, that moment is happening right…

🔥 “It’s Like the Comet Just… Shut Off”: Panic Ripples Through the Astro-Community as New 3I/ATLAS Images Reveal Zero Observable Activity, Leaving Scientists—and Brian Cox Himself—Rattled by the Possibility That Something Unseen Is Interfering With a Celestial Object That Should Be Roaring With Dust and Ice in the Vacuum of Space 😱🌌

Have you ever wondered if we’re truly alone in the universe? What if the evidence was already here, passing right…

End of content

No more pages to load