What if the most hunted man in modern history never faced the justice the world believed he did.

For eighty years, generations have been taught that Adolf Hitler died in his Berlin bunker on April 30, 1945.

The war ended.

The dictator was gone.

Case closed.

But the truth is far less certain than the textbooks suggest.

The Soviet Union never showed the body.

Stalin made public claims that Hitler had escaped.

The FBI kept active case files on potential sightings of Hitler in Argentina throughout the entire 1950s.

And when scientists finally examined the skull fragment displayed for decades in Moscow as proof of Hitler’s suicide, DNA tests showed it belonged to a woman.

What should have been one of history’s most straightforward forensic conclusions has instead remained a source of confusion, secrecy, and international suspicion.

The mystery continues to haunt historians, investigators, and the public because the physical evidence surrounding Hitler’s death is compromised, inconsistent, and incomplete.

The narrative taught in school left out critical questions that have never been fully resolved.

Let us begin with the part everyone thinks they know.

In April 1945 Berlin was a collapsing fortress.

Soviet artillery pounded the city from every direction.

Inside a dim concrete bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery, Adolf Hitler realized the end had arrived.

Every hour brought new reports of lost battalions, failed counterattacks, and Soviet soldiers pushing closer to the center of the capital.

Witnesses later described Hitler as a man unraveling.

On April 26 his generals delivered a final devastating message.

The war was effectively lost.

Hitler raged, blamed his closest allies, and then retreated into despair.

On the night of April 29 he married Eva Braun in a brief ceremony attended by a handful of loyalists while artillery shells shook the building above them.

The next morning Hitler withdrew into his private quarters with Eva.

Seconds later a gunshot echoed through the bunker.

When aides entered the room, they reported finding Hitler dead from a self inflicted gunshot wound while Eva lay beside him after consuming cyanide.

According to the official story, their bodies were carried to the garden, doused in fuel, and burned.

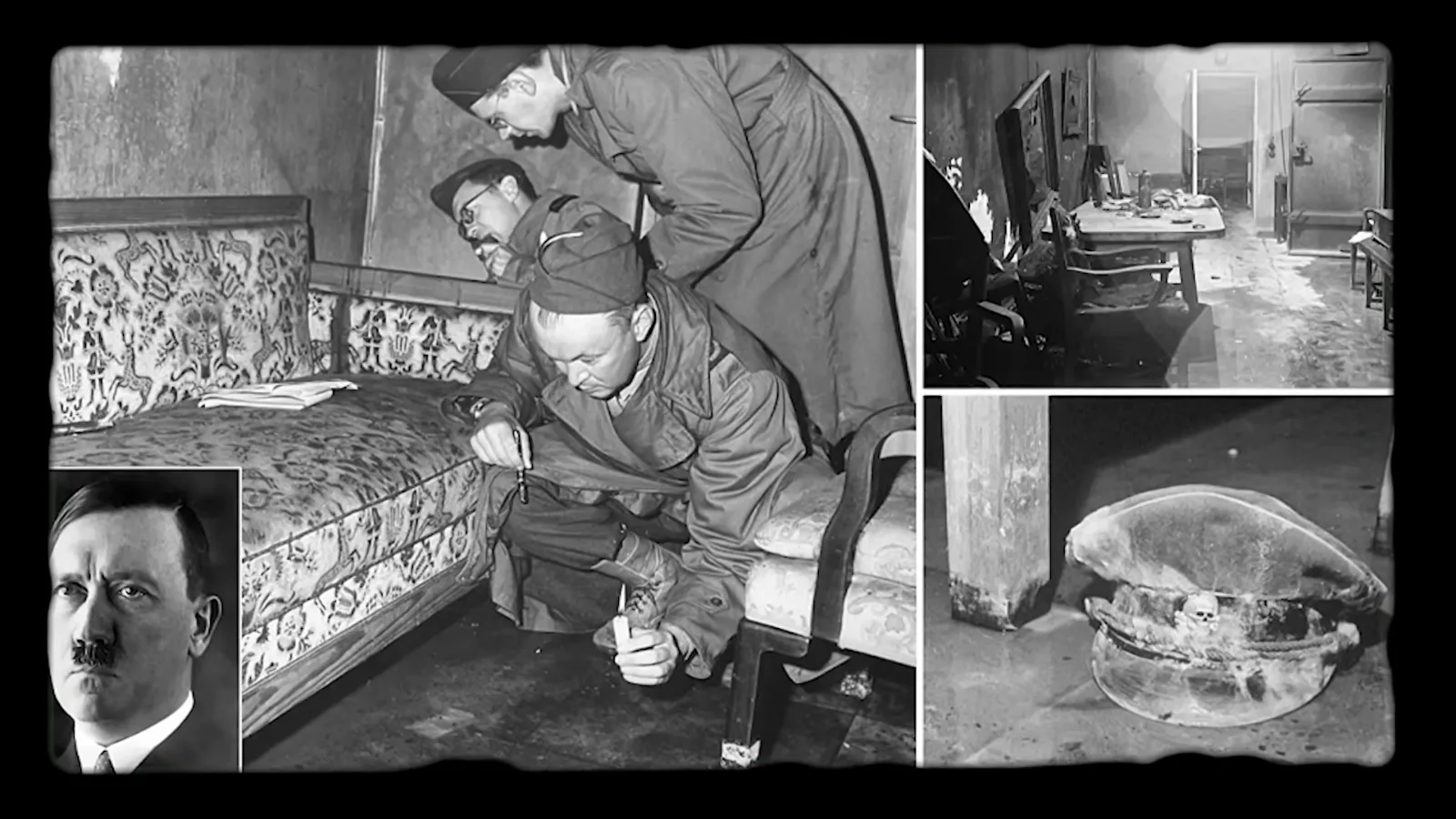

The Soviets arrived hours later and found charred remains that were quickly identified as Hitler and Eva Braun.

Thus ended the life of the man responsible for the deadliest conflict in human history.

It is a simple story.

It is also a deeply flawed one.

From the moment Soviet troops entered the bunker, the investigation into Hitler’s death was a disaster.

Soldiers took trophies instead of preserving evidence.

No photographs of the bodies exist.

The area was disturbed before any proper forensic examination could be conducted.

Fire experts later noted that the amount of gasoline used would not have been enough to cremate two bodies in open air.

Modern cremation requires extremely high sustained heat inside a sealed chamber.

A few cans of fuel dumped into a shallow crater during a bombardment would have left significant remains intact.

Some witnesses reported the recovered corpse looked slightly different from Hitler.

The Soviets first claimed they had recovered the body, then refused to show it to Western powers, and eventually Stalin began insisting Hitler had escaped.

Whether this was political manipulation or genuine suspicion, it had a profound effect.

By the end of 1945 nearly half of Americans believed Hitler might still be alive.

There was still no official death certificate until 1956.

He was declared dead without a body ever being produced for independent confirmation.

That uncertainty created space for darker theories.

The truth is that thousands of high ranking Nazis did escape Europe after the war.

This is not speculation.

It is documented fact.

Adolf Eichmann lived more than a decade in Argentina before being captured by Israeli agents.

Joseph Mengele evaded justice for decades and died in Brazil in 1979.

Klaus Barbie found refuge in Bolivia.

Walter Rauff lived freely in Chile.

These men used organized escape routes often called rat lines.

With forged documents, sympathetic clergy, and networks of former SS officers, fugitives could obtain new identities and passage to South America in a matter of days.

Argentina under President Juan Peron welcomed thousands of Germans, including known war criminals.

Many found work, homes, and safety in communities that spoke their language and shared their culture.

If other high profile Nazis could vanish so effectively, it is not surprising that theories emerged suggesting Hitler might have used the same mechanisms.

In 2011 a controversial book argued that Hitler escaped to Patagonia and lived there until 1962.

The book included testimony from individuals who claimed they encountered him in Spain or South America.

Declassified CIA and FBI files show that American intelligence agencies received numerous reports of men resembling Hitler living abroad.

One 1955 CIA document even includes a photograph of a man in Colombia said to be Hitler.

Most of these leads were never fully investigated.

Resources were limited.

The Cold War was beginning.

And the United States had little interest in reopening the question of Hitler’s death.

Some theories push the speculation even further by pointing to Nazi expeditions to Antarctica during the 1930s and the massive American military mission known as Operation Highjump in 1946.

The official explanation for this mission was scientific research.

But the size and scope of the operation led some to wonder whether there was another purpose.

To this day historians dismiss the Antarctica theories, yet they persist largely because of the secrecy that surrounded early Soviet reports.

There are strong arguments in favor of the bunker suicide narrative.

Hitler was obsessed with controlling his legacy.

He was psychologically incapable of living anonymously in exile.

He was horrified by the way Mussolini had been killed and displayed and vowed never to suffer the same fate.

His physical health was deteriorating.

His world was collapsing.

The suicide theory fits what psychologists know about him.

It fits the timeline.

It fits the motivations of a dictator whose empire was crumbling around him.

What muddies the waters is the physical evidence.

For decades the Soviet Union claimed it possessed Hitler’s remains.

These included a jaw fragment and a piece of skull with a bullet hole.

No Western scientist was allowed to examine them.

The skull fragment went on display in 2000 in Moscow.

In 2009 American researchers were granted limited access to conduct DNA testing.

Their findings stunned the world.

The skull did not belong to Hitler.

It did not belong to any man.

DNA analysis showed that it came from a woman under forty.

The fragment that had been shown to millions as the conclusive proof of Hitler’s death was nothing of the sort.

The revelation reignited decades of doubt and new questions.

Whose skull was it.

Why had the Soviets kept it.

Was it incompetence or deliberate misinformation.

The only remaining piece of evidence is the jawbone kept in Russian custody.

In 2017 a French team was finally allowed to examine it.

They compared it painstakingly to historical dental records and found an apparent match.

The dental bridges, the bone structure, the wear patterns, and even indications of a vegetarian diet aligned with what is known about Hitler.

The French team concluded that the jaw was likely authentic.

Most historians accept this conclusion.

But there remains a problem that can never be overlooked.

The chain of custody is broken.

The remains were moved, hidden, burned, reburied, and handled entirely outside independent oversight.

Modern DNA technology could solve the mystery completely, but Russia has not allowed full testing or comparisons with living relatives.

This lack of transparency sustains the debate, but the deeper reason the mystery refuses to die goes beyond science.

People struggle with the idea that someone responsible for the deaths of millions could choose the terms of his own ending.

He was never arrested.

He never stood trial.

He never faced his victims.

Compared to the Nuremberg trials that held other Nazi leaders accountable, his ending feels unfinished.

It feels too convenient, too quick, too private, too unexamined.

The Soviet secrecy that followed only deepened public mistrust.

When a government claims to possess the truth but refuses to share evidence, suspicion is inevitable.

All these factors created fertile ground for speculation that has lasted eight decades.

This matters because the way we understand the end of Hitler shapes how we think about justice, truth, and historical accountability.

When powerful figures commit atrocities, the world needs clear, transparent, independently verified evidence of what happens to them.

If evidence is withheld, manipulated, or destroyed, the result is doubt.

And doubt becomes a breeding ground for denial and distortion.

This is why modern war crimes are documented meticulously.

This is why international courts conduct public trials.

This is why forensic evidence is preserved instead of hidden.

History has shown what happens when secrecy replaces transparency.

Yet despite all the shadows surrounding this story, the weight of evidence still supports the conclusion that Hitler died in his Berlin bunker on April 30, 1945.

The dental records remain the strongest indicator.

The witness testimonies, though imperfect, are generally consistent.

The psychological context fits.

The alternative theories lack the hard proof needed to overturn the consensus of most historians.

What keeps the questions alive is not the evidence but the symbolism.

Hitler authored one of humanitys darkest chapters.

He caused destruction on a scale almost impossible to comprehend.

The idea that he slipped away and lived out his life in peace feels intolerable.

It feels unjust.

It feels wrong.

The world wanted a public reckoning.

It wanted a trial, a sentence, a moment of accountability.

Instead it received a story delivered by traumatized witnesses, managed by a secretive regime, supported by evidence that cannot be fully verified.

The ambiguity created an opening that has never fully closed.

But perhaps the significance of this story is not whether Hitler escaped.

The real lesson lies in why transparent evidence matters, why accountability must be visible, and why history must be documented with clarity rather than secrecy.

The ongoing search for definitive answers reflects a deeper human need for truth.

It reflects a refusal to let the crimes of the past fade into uncertainty.

It reflects a belief that justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done.

Hitler died in a bunker beneath a ruined city, surrounded by the consequences of his own destruction.

The empire he built collapsed.

His ideology continues to be rejected by the world.

And yet the questions surrounding his final moments remain alive because history demands evidence, not shadows.

That insistence on proof, accountability, and transparency is perhaps the most important legacy of this unresolved mystery.

News

The Ethiopian Bible Reveals What Jesus Said After His Resurrection — Hidden for 2,000 Years! ff

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most extraordinary and controversial religious artifacts in the world. Believed by many…

DEVASTATING NEWS ON R KELLY IN PRISON!

You’re watching Ticket TV. Like, share, and subscribe on your way in. All right, man. Salute to everybody tapping on….

R Kelly survivor reclaims her name and power in new memoir

A once anonymous R Kelly survivor is reclaiming her voice in a new memoir. Rashona Lanfair was known as Jane…

Anton Daniels The R-Kelly of Youtube | Busted for Hooking up with? Unbelievable

Anton Daniels, the R Kelly of YouTube, busted for hooking up with who? Well, word on the street and the…

R Kelly Prison Release Date Dec 21, 2045 Over 20 More Years!

The federal sentencing of R Kelly has entered a new chapter as updated correctional records confirm a projected release date…

El Mencho Final Mistake : The Woman Who Led FBI Right to Him – Betrayed by Love?

February 21st, 2026. A woman arrives at Cababanas Loma, a vacation compound nestled in the mountains of Talpa, Jaliscoco, Mexico….

End of content

No more pages to load