The Collector

In Charleston’s historic district — where gas lamps still flicker at dusk and the cobblestone streets echo with carriage wheels — there lived a man named Elliot Grayson.

He was a recluse, a collector of oddities and rare antiques. Those who knew him said his townhouse resembled less a home and more a museum of the macabre.

He owned death masks from the French Revolution, Victorian mourning jewelry woven from human hair, and even a taxidermied chimp dressed in a 19th-century sailor suit. His collection was legendary among private dealers, whispered about in auction houses and estate sales across the country.

But nothing fascinated him more than the Victorian obsession with preserving beauty after death — that fragile line between art and corpse.

So when an antique dealer from Savannah called him in June of 2019 about a “one-of-a-kind Victorian life-size doll,” he didn’t hesitate.

The Sale

The shop was small, tucked between a pawn store and a shuttered bakery. Its sign read: HOLLAND & SONS: RARE CURIOS AND ESTATE FINDS.

Inside, it smelled faintly of dust and lavender oil. Shelves overflowed with glass-eyed mannequins, cracked porcelain busts, and faded tintypes of long-dead strangers.

At the back of the room, under a dim chandelier, she stood.

The doll was life-sized — a young woman seated in a carved mahogany chair, her posture demure, her dress a faded ivory lace gown with mother-of-pearl buttons.

Her face was… breathtaking. Pale, smooth, and eerily lifelike. Her lips were slightly parted, as though mid-breath. Her eyes — deep gray with a faint glassy sheen — seemed to follow him.

And her hair, a cascade of dark brown curls, shimmered under the light.

“Circa 1870s,” the dealer explained softly. “Made by a mortuary artisan in England. The skin is porcelain, treated with a secret glazing technique that imitates human translucence. The hair, however, is real. Taken, they say, from the artist’s deceased wife.”

Elliot was entranced.

When the dealer quoted the price — $2 million — he didn’t flinch.

Within days, the doll was transported to his Charleston townhouse.

The Appraisal

Elliot invited a small team from the Carnegie Appraisal Institute, specialists in 19th-century funerary art, to evaluate his prize.

They arrived on a hot July afternoon.

The team’s lead appraiser, Dr. Lydia Monroe, began with standard documentation: age, materials, origin. But as she examined the “porcelain,” she noticed irregularities.

Under magnification, the surface wasn’t uniform like fired ceramic. It was fibrous, almost organic. The texture reminded her of aged parchment — but far more elastic.

She tapped gently on the cheek. The sound was dull, not hollow.

She tried a simple solvent test, rubbing a sterile swab along the arm’s surface. A faint residue lifted off — pinkish, like oxidized skin oil.

Her assistant frowned. “Dr. Monroe… this isn’t porcelain.”

The Revelation

By the end of the day, they’d taken micro-samples — with Elliot’s reluctant permission — for spectrographic analysis. The results, received three days later, changed everything.

The material wasn’t ceramic, resin, or wax.

It was human dermal tissue, preserved with a mix of arsenic-based embalming fluid and unknown compounds.

The “veins” visible beneath the surface weren’t painted — they were real.

The doll’s fingernails contained traces of keratin and cellular residue. The eyelashes were rooted directly into follicular tissue. Even the eyes, which everyone assumed were glass, turned out to be biological, reinforced with a clear polymer film.

The doll wasn’t crafted.

It was constructed — from the remains of a real woman.

The Investigation

Charleston Police launched an immediate investigation, seizing the doll as evidence. Forensics confirmed the body was female, approximately twenty years old at the time of death, preserved sometime between 1870 and 1890.

But the methods used to preserve her were far more advanced than any known Victorian technique. The embalming was intricate — surgical incisions resealed with near-invisible stitching, muscle and bone structures replaced with articulated brass joints.

Whoever made her had been both anatomist and artist.

When police questioned the antique dealer, Jonathan Holland, he claimed he’d acquired the doll from a private estate in London. The paperwork was minimal — a handwritten receipt dated 1984, signed by someone named “M. Gray.”

But when investigators traced Holland’s sales history, they found something else.

Over the past decade, several of his “rare acquisitions” had been linked to missing persons cases across the Southeast. Clients reported receiving crates of “authentic Victorian pieces” that later tested positive for human biological material — teeth, bones, and tissue samples.

Holland’s shop was raided.

In the basement, police discovered sealed wooden crates containing partial mannequins, torsos, and limbs in varying states of preservation. Some were modern.

Several matched the DNA of missing persons reported between 2005 and 2017.

The Workshop

Forensic reconstruction revealed a horrifying truth: Holland wasn’t merely selling antiques — he was manufacturing them.

Inside a hidden workspace beneath the shop, investigators found surgical tools, industrial preservatives, molds, and pages of handwritten notes detailing the “process.”

One entry read: “True art requires truth of form. Porcelain cracks, wax melts, but flesh endures when properly prepared. She becomes eternal — my beautiful dolls.”

The notes detailed his experiments in “modern embalming composites” — a blend of synthetic polymers and organic tissue to “simulate life indefinitely.”

But there was one chilling section labeled “Prototype I — Eleanor.”

That was the doll Elliot had purchased.

The file included photographs from 1871: a young woman, labeled Eleanor Gray, believed to be the artist’s wife — missing, presumed dead. The last image showed her seated in a chair, eyes open, body rigid.

He had preserved his wife.

He’d turned her into art.

And over a century later, Holland had somehow found her, restored her — and sold her again.

The Aftermath

Elliot Grayson’s townhouse was seized as part of the investigation. He was cleared of wrongdoing but refused to grant interviews afterward. Those who knew him said he became a shell of himself, shutting his collection away and leaving Charleston altogether.

The “Eleanor Doll,” as it came to be called in the press, was kept in an evidence vault for over a year before being transferred to the Smithsonian’s Department of Forensic Anthropology for long-term study.

Even now, researchers say her preservation defies explanation. Despite exposure to heat and humidity, her form has not deteriorated. Her skin remains supple. Her eyes retain their eerie clarity.

And sometimes — when the lab is dark and quiet — technicians claim they hear faint creaks from the joints, as though she’s shifting ever so slightly in her chair.

Months after Holland’s arrest, a sealed envelope arrived at Charleston PD, postmarked from Vienna, Austria. Inside was a handwritten note: “You found Eleanor. I see you’ve met her again. But she was never mine alone. There are others — sisters, perfected, waiting to be adored.”

No return address.

Interpol traced the ink and paper to a rare stationary supplier used by antique dealers in Europe.

Since then, reports have surfaced from collectors in Prague, Paris, and Tokyo — all describing eerily lifelike “Victorian dolls” appearing at private auctions. Each is said to have the same soft skin, the same glassy eyes… and the same faint smell of lavender and arsenic.

The Doll That Breathed

In early 2022, one of the Smithsonian’s researchers swore he saw Eleanor’s chest rise and fall, ever so slightly, as though drawing breath.

Security footage later showed the doll’s hand had shifted position between frames — fingers curling subtly against the chair’s armrest.

The footage was never released.

When questioned, the museum cited “optical interference.”

But that researcher quit a week later, leaving only a note behind: “She’s not dead. She never was.”

The shop on King Street was demolished in 2020. Yet locals still claim that late at night, near where it once stood, you can smell lavender — and hear the faint hum of machinery beneath the ground.

As for the Eleanor Doll, she remains locked in a temperature-controlled chamber, sealed from the public.

But if you ever find yourself in Charleston, and you visit the museum’s restricted wing, look closely through the glass.

You might notice that her eyes — those haunting gray eyes — don’t just reflect the light.

They follow it.

And if you listen closely, you might hear a soft creak — the sound of a chair slowly shifting, waiting for the next collector to come calling.

News

🎰 The Tragic Fade of Nate Diaz: From Stockton’s Street-Bred Warrior to a Legend in Limbo

For years, Nate Diaz embodied everything raw, rebellious, and real about mixed martial arts. He was the antithesis of corporate…

🎰 5 Hollywood Stars Dolph Lundgren Refuses to Work With Again — And the Shocking Stories Behind Each Feud

Dolph Lundgren became a global icon the moment he stepped onto the screen as Ivan Drago in Rocky IV—ice-cold, intimidating,…

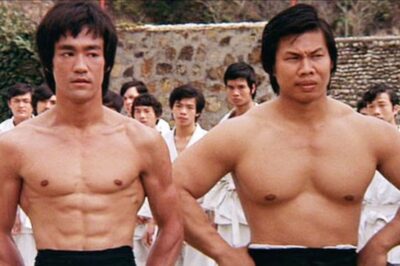

🎰 Bruce Lee, Bolo Yeung, and the Truth Behind the Silence

For decades, Bruce Lee’s death has been surrounded by noise. Rumors. Theories. Sensational headlines designed to shock rather than explain….

🎰 Ravishing Rick Rude: The Perfect Heel, the Broken Body, and the Death Wrestling Still Won’t Explain

“Was he intense in the ring?” “Oh yeah. He was wound tight.” “Dangerous?” “Very.” That single word—dangerous—follows Rick Rude through…

🎰 Larry Holmes’ Pennsylvania Country Life — From Heavyweight Glory to a Quiet Legacy

Fame once followed Larry Holmes everywhere.Roaring arenas. Flashing lights. The weight of a heavyweight crown. Today, his story unfolds far…

🎰 How Riddick Bowe Lives Today: From $80 Million to Brain Damaged and Broke

Riddick Bowe was the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world.He beat Evander Holyfield in 1992.He made over $80 million in…

End of content

No more pages to load