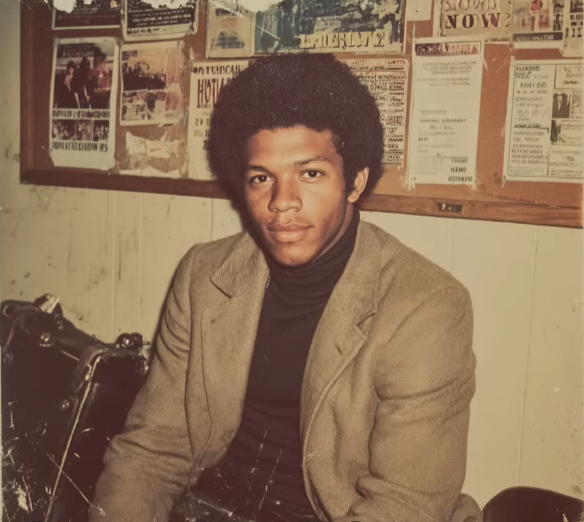

In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1974, the city’s oldest historical museum opened its newest attraction — a Civil War exhibit featuring what it called a “remarkably lifelike” wax figure of a Black Union soldier.

Visitors marveled at the realism. The detailing in the skin, the faint scars, the glassy eyes that seemed almost alive.

Some even said it was too real. But the museum assured everyone it was simply the work of an exceptionally talented artisan — a haunting yet educational tribute to forgotten soldiers of the past.

For nearly five decades, the figure stood silently in its glass case. Children took class photos beside it. Historians wrote about it in papers.

Tourists whispered about the eerie realism, but no one ever looked closely enough to see what it really was.

Until 2024.

The Curator Who Looked Too Close

When Dr. Elise Porter, a newly appointed curator and forensic anthropologist by training, began her work at the Baton Rouge Museum of History, one of her first projects was to update and restore the aging Civil War display.

At first, it seemed routine — cataloging old uniforms, replacing faded placards, and cleaning the so-called “wax figure” that had long been the exhibit’s centerpiece.

But as she inspected it under a restoration lamp, something caught her attention.

The texture of the skin wasn’t waxy — it was fibrous. There were subtle pores, hair follicles, and even the faint pattern of fingerprints on one hand.

Porter stopped.

When she ran a non-invasive spectrometer scan, her heart sank. The results were unmistakable: organic tissue.

The “wax figure” wasn’t made of wax at all. It was human.

Authorities were immediately called in. The exhibit was sealed off as forensic experts and detectives arrived to investigate what was now a potential crime scene hidden in a museum.

Initial tests revealed the remains belonged to a Black male in his mid-30s, dating back to the late 20th century — not the Civil War era as previously believed.

Further analysis confirmed something even more shocking: dental records matched those of a local man named Henry Walters, who had vanished from Baton Rouge in 1973, just months before the museum opened the exhibit.

For fifty years, Henry Walters had been missing — while his body stood on public display, mistaken for art.

How Could No One Have Known?

As investigators dug deeper, they discovered a tangled trail of misplaced paperwork, old museum acquisitions, and questionable donations from private collectors in the 1970s.

Records showed that the “figure” had been acquired anonymously, labeled only as “Wax Reconstruction — Donated by Estate.”

No one questioned it at the time — a grim oversight that blurred the line between education and exploitation.

Experts now believe that the body may have been embalmed and chemically treated, giving it a wax-like appearance and halting decomposition.

Over time, museum humidity controls and glass casing preserved the remains — turning Henry Walters into a macabre exhibit piece.

The revelation sent shockwaves through the museum community and beyond. Local police reopened the Henry Walters missing person case, now reclassified as a suspicious death investigation.

DNA evidence confirmed his identity, but the biggest question remained unanswered: How did Henry end up in the museum?

Some theories suggest body trafficking or medical misuse during the 1970s, when anatomical specimens often changed hands with little regulation.

Others believe his body may have been stolen from a morgue or unclaimed remains used without consent — a chilling echo of historical exploitation practices.

A Museum’s Reckoning

The Baton Rouge Museum of History has since closed its Civil War wing indefinitely and issued a public apology to the Walters family.

Dr. Porter, the curator who made the discovery, described the moment as “devastating and humbling.”

“For fifty years, people looked at him and never saw the person he was,” she said. “Now, finally, he has a name — and a story.”

The museum has pledged to return Henry Walters’s remains to his surviving relatives for proper burial and to install a memorial honoring both his life and the countless others whose stories have been overlooked or erased.

What began as a dusty exhibit turned into one of Louisiana’s most disturbing true-crime cold cases — a mystery hidden behind museum glass for half a century.

The story of the “wax figure that wasn’t” forces both historians and the public to confront uncomfortable truths about how easily humanity can be forgotten in the name of history.

Because sometimes, the past isn’t just behind glass — it’s looking back at us.

For fifty years, Henry Walters stood silently in a display meant to teach history — and in doing so, became history himself.

His rediscovery reminds us that truth often hides in plain sight, waiting for someone brave enough to finally look closer.

News

🐻 The Ultimate Warrior Fan Encounter That Turned Into His Darkest Moment

He sprinted to the ring like a man possessed — veins bulging, tassels flying, an icon painted in neon colors…

🐻 Wrestlers Who Went Insanely Broke – From Luxury Lives To Shocking Ruin

They once lived like gods — champagne, limousines, private jets, and fame that stretched around the world. The kings and…

🐻 Mike Tyson was separated by countless security from opponent who later tried to sue him for $2 million

Mike Tyson’s series of controversial fights continued on this day in 1999. While Tyson’s iconic knockouts in the heavyweight division…

🐻 The Eerie Benoit Wikipedia Mystery – “someone Knew Before The World Did”

It remains one of the most chilling and inexplicable moments in both wrestling and internet history. June 24, 2007. The…

🐻 When Ric Flair Traveled to North Korea for the Biggest Wrestling Show of All Time

Whether he was in a dimly lit convention center in front of a few dozen people or headlining packed arenas…

🐻“Mr. Wonderful” Paul Orndorff – The Tragic Final Years Of A Wrestling Legend

He was Mr. Wonderful — the sculpted powerhouse with charisma, confidence, and a right hand that could drop giants. Paul…

End of content

No more pages to load