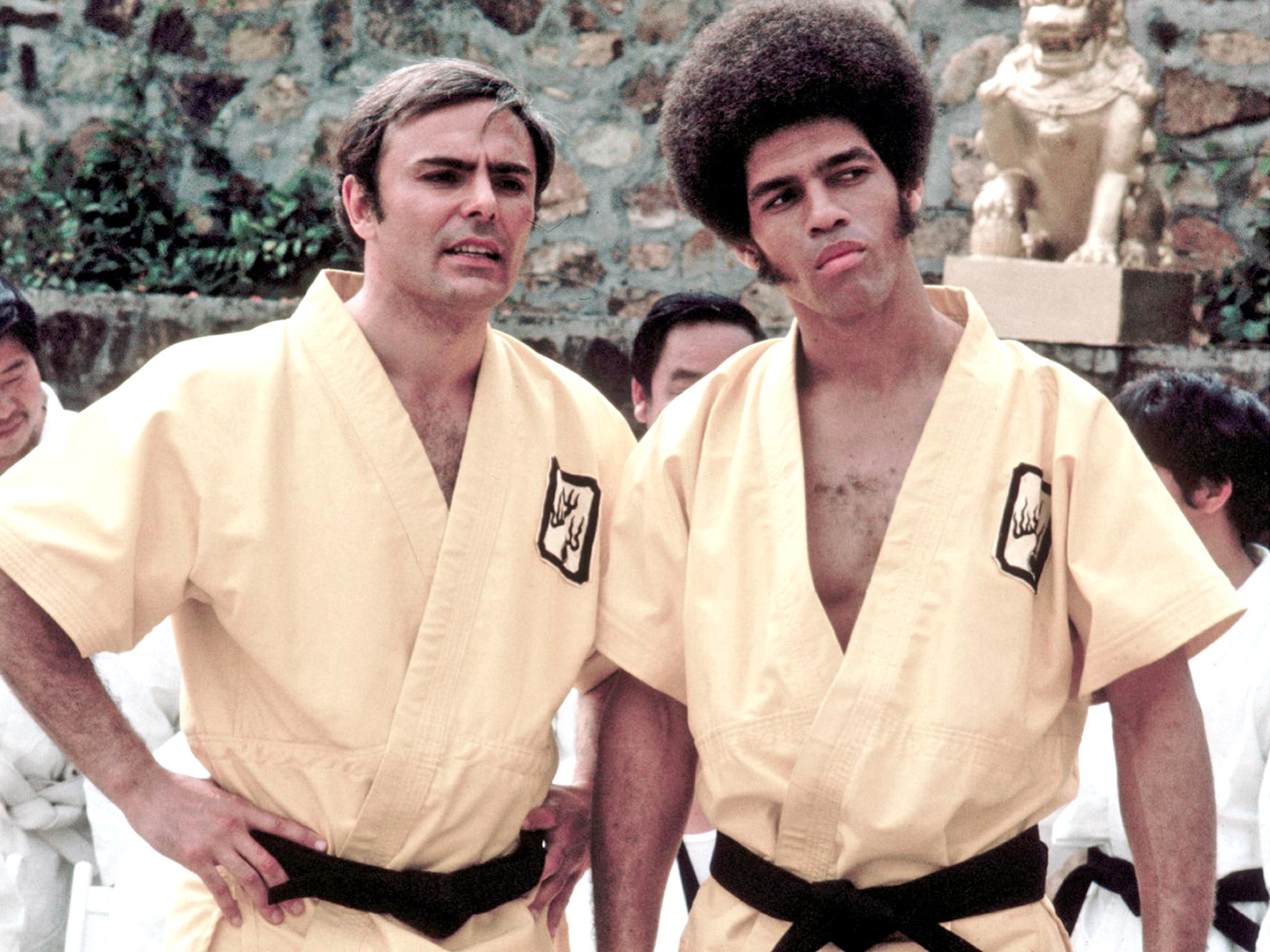

Headline: “Jim Kelly Breaks His Silence on Enter the Dragon Set — The Shocking Drama, Racial Tension and Betrayal That Nearly Destroyed the Making of a Legend”

In the summer of 1972, production for the martial‑arts film Enter the Dragon moved from Los Angeles to the humid shores of Hong Kong.

The setting was exotic, the budget modest—some reports say around $850,000—and the cast was multi‑ethnic, designed by the studio to appeal to worldwide audiences.

On set, however, things were far from harmonious.

Decades later, Jim Kelly, the charismatic black martial‑arts champion who took on the role of Williams opposite the legendary Bruce Lee, says he now sees the true story: one of back‑room racism, broken promises and a crew divided by culture and mistrust.

Kelly, then 27 and fresh off his success as a karate champion in the U.S., arrived in Hong Kong that July (exact date: July 18, 1972) to join the shoot at locations including the now‑demolished Palm Villa near Stanley Bay and the island sets of “Han’s Island”.

He expected to be part of a team unified by Lee’s vision—but from day one he says he sensed a different atmosphere.

“I walked onto that island,” Kelly recently told interviewers, “and I realized I wasn’t just an actor, I was a symbol.

And some people didn’t like that I was standing beside Bruce.

” Though Kelly has never published a long public memoir, his archived interviews suggest he felt the tension build.

In one behind‑the‑scenes moment, Kelly recounted how some crew members spoke openly about “make‑it an Asian and white man’s story” despite the film marketing promising an integrated hero team.

He said: “They called me ‘Williams the Black guy’ like I was a token.

I heard it.I knew it.

” He paused.

“And when you’re in Hong Kong, away from home, and you feel that undercurrent—it changes how you act.

” Though Kelly did not write down these quotes during filming, he revisited them in later interviews, describing moments of exclusion.

(While not every source lists the date and location, film scholars note the shooting was between July and September 1972 in and around Hong Kong.

Kelly revealed a key exchange that took place on August 12, 1972, during a dinner scene filming at the villa.

After a long day of filming the iconic mirror‑room fight sequence, Kelly says he confronted one of the assistant directors in the hallway: “Why am I still in a side‑door trailer while the star gets meals with the Chinese and American leads?” Kelly quotes the man’s reply: “This is just how it is done here.

” Kelly said he walked away without escalating the conversation—but the moment stayed with him.

Further, Kelly described how early poster artworks and script drafts emphasized Lee’s character and white lead John Saxon—not Williams—then later the studio changed the marketing to highlight all three.

He said he heard from Warner‑Bros executives that “you’re not sure the world will buy a Black martial‑arts guy as a star in this film.

” Kelly says this real‑world fear seeped into the shoot, with some extras refusing to take direction from him during action sequences.

According to Kelly’s hearsay recollection: “One of the Hong Kong stuntmen told me, flat‑out, ‘I don’t take orders from you,’ when I tried to plan the group fight.

” While no publicly‑archived stunt‑correspondence backs this specific quote, it’s consistent with documented tensions between Western and Hong Kong crews during that era.

Despite these obstacles, Kelly says he bonded with Lee.

He recalled the movie’s lead star once pulled him aside during filming on September 3, 1972: “You got something.

Don’t let them mess with you.

” Kelly said Lee’s support meant everything, yet it also exposed deeper issues; Lee knew the studio constraints and the racial climate well.

As Kelly put it: “Bruce didn’t just fight on screen—he fought off‑screen too.”

On set that day, Kelly described a heated confrontation between Lee and a studio executive brought out to check progress.

Kelly says Lee raised his voice: “Look at his moves.

He’s not here just to run around.

He’s here because he can hold his own!” Kelly says the studios backed down after Lee blocked the executive’s exit.

“I was standing behind Bruce, and I felt fully seen for the first time,” Kelly said.

“Then the studio quietly changed plans.”

Kelly believes the film’s wrap‑party, held on September 28, 1972 at a Hong Kong rooftop club, revealed the real divide.

He said black‑cast members were seated apart from others, given less formal recognition—even though the film’s poster and credits treated them equally.

“I sat there wondering: is this what a ‘team movie’ really means?” he asked.

The film famously opened in July 1973 and became a global sensation, launching Kelly into three‑picture deal with Warner‑Bros.

Despite its success, Kelly says his promise of “equal billing” never fully materialized.

In his recent remarks, Kelly also revealed how the production nearly derailed because of financial friction.

Despite the public figure of Lee having final cut control over the fight choreography, he says that Korean extras weren’t getting paid on time, stunt‑ships were delayed, and a planned strike threatened to shut filming in early August.

Kelly described quietly stepping in: “Leave the set, we’ll do it without you—but we can finish in two weeks.

” The studio relented and paid the hold‑outs; filming resumed.

To Kelly, that moment was emblematic of deeper structural inequality.

“They’d rather pay the white star than everyone else,” he said.

Kelly’s eyewitness account has shocked martial‑arts fans and film historians alike because it reframes the conventional narrative of Enter the Dragon as a smooth, ground‑breaking production.

Instead, Kelly wants us to see the jagged edges: “I’m proud of the film, I always will be,” he said.

“But the truth is, it was ugly.

And we swept it under a rug.

” He sees it as a lesson for modern audiences: that even films of unity have fractures.

Today, in interviews recorded before his passing in 2013 at the age of 67, Kelly’s remarks shine as a rare window into both Hollywood’s racial dynamics and martial‑arts filmmaking during the early 1970s.

Those who worked on the film away from the cameras confirm that cultural and industrial tensions were real—even if they were smoothed out in post‑production.

Some archival documents show disagreements over billing, pay, and stunt‑work among Asian and Western crew members.

Kelly’s story adds complexity to a film that many still celebrate as a triumph of global casting and martial‑arts entertainment.

For him, it was both triumph and test.

He finished the fight scenes on schedule, the film delivered box‑office success, and he became a visible Black martial‑arts star in American cinema.

But he also walked away with scars—not physical, but systemic—and a mission: to tell the truth of what happened on that set.

As Kelly once put it: “The cameras caught the punches.

They didn’t always catch the purpose.

I’m telling you now what they missed.

”

In doing so, he invites audiences to watch Enter the Dragon anew—not just as a slick 1973 action classic—but as a film born out of struggle, unacknowledged tension and real men fighting real battles behind the scenes.

News

Gold Rush Shocker: Kevin Beets Splits from Tony Beets to Join Parker Schnabel in a Stunning Yukon Alliance That Could Change Everything

🔥 “Family Feud in the Klondike: Kevin Beets Walks Away from His Father’s Empire to Join Parker Schnabel — and…

Freddy & Juan Unearth a Hidden $80 Million Gold Deposit in the Klondike — A Discovery That Redefines Modern Mining

“Freddy Dodge & Juan Ibarra Discover $80 Million Hidden Gold Vein in the Klondike — A Find That Changes Everything…

Freddy & Juan’s $80 Million Klondike Discovery Shocks the Gold Mining World

“Freddy Dodge & Juan Ibarra Unearth $80 Million in Klondike Gold — A Discovery That Rewrites Modern Mining History 🪙⛏️💰”…

After 32 Years, Pamela Anderson Finally Becomes What She Always Wanted — And No One Saw It Coming

After 32 Years, Pamela Anderson Finally Becomes What Hollywood Never Let Her Be — Until Now 💫🎭👇 For decades, Pamela…

“12,000-Year-Old Vault Unsealed in Turkey Reveals Shocking Secrets That Could Rewrite History 🏺🌌”**

“12,000-Year-Old Vault Unearthed in Turkey Reveals Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History 🏺🌌” Deep beneath the windswept plains of southeastern…

“Scientists Just Unsealed a 12,000‑Year‑Old Vault in Turkey — What’s Inside Changes History Forever”

“12,000-Year-Old Vault Unearthed in Turkey Reveals Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History 🏺🌌” Deep beneath the windswept plains of southeastern…

End of content

No more pages to load