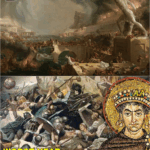

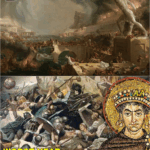

🌑 The Year the Sun Vanished: How 536 AD Plunged the World Into Darkness and Changed Humanity Forever ❄️

Historians and scientists agree that if you could travel back to any year in the past, the one you’d least want to visit is 536 AD — a year so catastrophic that it plunged much of the world into darkness for nearly two years.

It wasn’t a war, a plague, or a political collapse that began it all.

It was something far more mysterious — a shadow that fell over the Earth itself.

The story begins in the spring of 536.

Across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, chroniclers recorded something strange: the sun had dimmed.

It was not an eclipse — it lasted far too long.

Byzantine historian Procopius wrote, “The sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon during an eclipse, and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.

” Days felt like dusk.Crops withered.Temperatures plummeted.

In Ireland, ancient annals recorded “a failure of bread from the years 536 to 539.

” In China, summer snow fell, rivers froze, and farmers starved as harvests failed.

The air grew cold and dry; birds migrated early and never returned.

It was as if the world’s heartbeat had slowed.

Modern scientists long debated what could have caused such a global catastrophe.

Only recently have they pieced together the evidence — microscopic volcanic ash found in ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica revealed that a massive volcanic eruption, or perhaps several, had occurred almost simultaneously around the world.

One likely culprit: an enormous eruption somewhere in Iceland or North America that hurled millions of tons of ash and sulfur into the stratosphere, forming a veil that blocked sunlight for over a year.

The effects were devastating.

Global temperatures dropped by as much as 2.

5°C, triggering the coldest decade in more than 2,000 years.

Crops failed across continents.

The Byzantine Empire, already weakened by wars, faced widespread famine.

In China, the Northern Wei dynasty collapsed amid chaos.

And in Europe, starvation and disease decimated entire villages.

But the darkness of 536 was only the beginning.

The chain reaction that followed would reshape the course of history.

By 541, just five years later, the first recorded outbreak of bubonic plague struck Constantinople — the infamous Plague of Justinian.

Historians estimate it killed between 30 and 50 million people — nearly half of the world’s population at the time.

The combined blow of famine, disease, and economic collapse plunged Europe into what historians now call the Dark Ages.

“It was as if the world had been reset,” said Harvard historian Michael McCormick, one of the scholars who analyzed ice core data to pinpoint 536 as humanity’s “worst year.

” “You can see it in the archaeology — the collapse of trade, the abandonment of cities, the sudden halt of cultural progress.

Civilization itself was knocked back centuries.”

Archaeological digs in Scandinavia tell a haunting story.

Entire communities vanished.

Graves from the period show mass burials with no signs of battle — only starvation.

In one chilling discovery, archaeologists found the remains of families who had died inside their homes, their last meals still in cooking pots turned to ash.

Legends from this time also carry echoes of the catastrophe.

Norse mythology speaks of Fimbulwinter — the “great winter” that preceded the end of the world.

Celtic folklore tells of “a year without a summer.

” Chinese historians recorded strange halos around the sun and moons that glowed red for months on end.

It seems that across cultures, humanity remembered the same nightmare.

As the centuries passed, the cause of that terrible darkness was forgotten.

The medieval mind blamed God, demons, or omens in the heavens.

But modern science, through the study of ice cores, tree rings, and ancient records, has reconstructed the chain of events: a massive volcanic eruption in 536, followed by two more — one in 540 and another around 547 — that ensured the planet remained shrouded in gloom for nearly a decade.

In Greenland’s ice, layers from those years still hold traces of sulfuric acid, evidence of the ash clouds that dimmed the sun.

“It’s like reading a diary written by the Earth itself,” said climatologist Ulf Büntgen.

“And 536 is the chapter where everything goes wrong.”

Even the great empires could not escape.

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian attempted massive construction projects — including the rebuilding of the Hagia Sophia — to assert divine favor, but the plague and famine that followed 536 drained his empire’s strength.

In Britain, the already-fragile post-Roman kingdoms fell into deeper isolation, a darkness both literal and cultural.

Yet, from this collapse, new civilizations slowly emerged.

The hardships of the mid-6th century reshaped the balance of power in Europe and Asia, setting the stage for the rise of Islam, the spread of Christianity into northern Europe, and the birth of medieval kingdoms that would later dominate the continent.

Still, for decades after 536, the skies remained dimmer than normal.

Generations grew up never knowing true daylight.

To them, the gray haze was normal — the only world they had ever seen.

It’s easy to forget how fragile human life is when nature turns against us.

The people of 536 didn’t have science to explain the darkness.

They didn’t know about ash particles or climate disruption.

To them, the sun simply died — and with it, hope itself.

Historians now call it “the worst year to be alive.”

But for the millions who endured it, the year 536 wasn’t just history — it was the end of the world.

And as researchers warn that a single massive eruption today could trigger similar effects, the memory of 536 serves as both a mystery and a warning — a reminder that civilization’s light has flickered before, and one day, it might again.

News

🌑 The Year the Sun Died: How 536 AD Plunged Humanity Into Darkness and Famine ❄️

🌑 536 AD: The Year the Sun Vanished, Plunging the World Into Darkness, Famine, and Fear ❄️ The year 536…

🕰️ “We Saw the Year 2749”: The Terrifying Testimony of Two Men Who Claimed to Have Traveled Beyond Time 👁️🗨️

⏳ Lost Between Centuries: The Haunting Story of Two Men Who Claimed to Return from the Year 2749 — and…

🚨 The Chilling Claims of Time Travelers: Inside the Terrifying Secrets They Say They Brought Back from the Year 2749 👁️🕰️

⏳ “We Saw the Year 2749”: Time Travelers Reveal a Future So Dark It Should Have Stayed Hidden 👁️🗨️ It…

🚛 The Last King of the Ice Roads: Inside the Life, Legends, and Near-Death Secrets of Alex Debogorski — The Man Who Laughed at the Arctic ❄️

🚛 Into the Frozen Unknown: The Untold Story of Alex Debogorski — The Ice Road Trucker Who Laughed in the…

🚛 The Unstoppable Spirit of Alex Debogorski: Inside the Life, Laughter, and Legacy of the Ice Road Trucker Who Became a Legend ❄️

🚛 Laughing in the Face of Frost: The Untold Life of Ice Road Legend Alex Debogorski — The Man Who…

🚛 Into the White Abyss: The Mysterious Disappearance of Ice Road Legend Lisa Kelly Beneath the Frozen Arctic Sky ❄️

🚛 Vanished on the Ice: The Chilling Mystery of Lisa Kelly’s Final Journey Into the Arctic Darkness ❄️ The Arctic…

End of content

No more pages to load