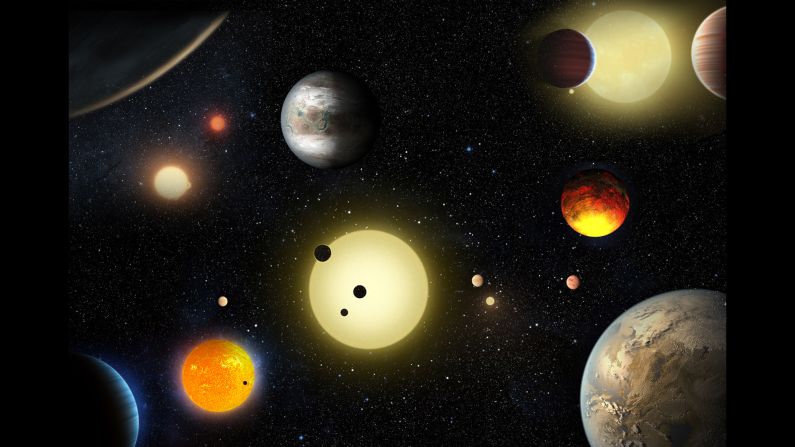

NASA’s Kepler mission uncovers thousands of exoplanets, including several Earth-sized worlds in the habitable zone that could potentially support liquid water.

When NASA launched the Kepler Space Telescope in 2009, few imagined how radically it would reshape humanity’s understanding of the cosmos.

Built for one mission—to stare continuously at a single patch of the Milky Way and hunt for planets orbiting distant stars—Kepler spent nine years capturing some of the most significant astronomical data ever recorded.

What scientists have uncovered inside that data, including Earth-sized worlds with water vapor, planets with potential seasons, and entire solar systems more bizarre than anything in science fiction, suggests the universe may be teeming with habitable worlds.

And what is truly astonishing is that many of Kepler’s most exciting discoveries were not recognized until years after the spacecraft was retired.

Kepler’s engineering alone was groundbreaking. Equipped with the largest primary mirror ever sent into space at the time and a 96-megapixel camera, the telescope monitored more than half a million stars.

Its job was to identify tiny, periodic dips in starlight—signals that a planet had passed in front of its host star.

Catching this dimming required almost impossible sensitivity: for a planet the size of Earth, orbiting a star like our Sun, the brightness drops by less than 0.01 percent. Yet Kepler succeeded, confirming 2,662 new exoplanets and revolutionizing planetary science.

Most of these worlds were unlike anything in our solar system. Many were enormous gas giants orbiting so close to their stars that a single year lasted only a few days.

Others featured hemispheres of molten lava, iron-melting temperatures, or orbits around binary suns that would give any observer two sunsets.

And still, Kepler’s most influential finding—and its most tantalizing—was the identification of small, rocky, temperate planets within a star’s “habitable zone,” the region where surface water can exist as a liquid.

One such world, K2-18b, sent shockwaves through the scientific community in 2019. Located 124 light-years from Earth, the exoplanet is almost eight times the mass of our own world and three times the size, orbiting a cool red dwarf star.

Using data from Hubble and Spitzer, two independent research teams identified signs of water vapor in its atmosphere—the first time water had been detected on a super-Earth in the habitable zone.

For astronomers, this marked a historic milestone: the earliest compelling indication that a relatively nearby planet could host the chemical foundations for life as we know it.

Red dwarfs, the most common stars in the galaxy, are now considered prime targets in the hunt for Earth-like planets. Kepler’s data suggests roughly six percent of red dwarfs may harbor a rocky world in the Goldilocks zone.

While the conditions on each vary, the statistical implication is enormous. If even a small percentage of these planets host water, the Milky Way could contain billions of environments capable of sustaining biology.

Kepler’s influence continued with the earlier discovery of Kepler-186f, a planet 500 light-years away that captured global attention in 2014. Roughly Earth-sized and orbiting within its star’s habitable zone, the planet initially seemed promising but poorly understood.

Years later, analyses from Georgia Tech researchers revealed that its axial tilt appears stable—similar to Earth’s—which could imply the presence of seasons and a climate cycle. If true, Kepler-186f may be one of the most Earth-like planets ever identified.

Yet even these discoveries pale compared to revelations from re-examined Kepler data.

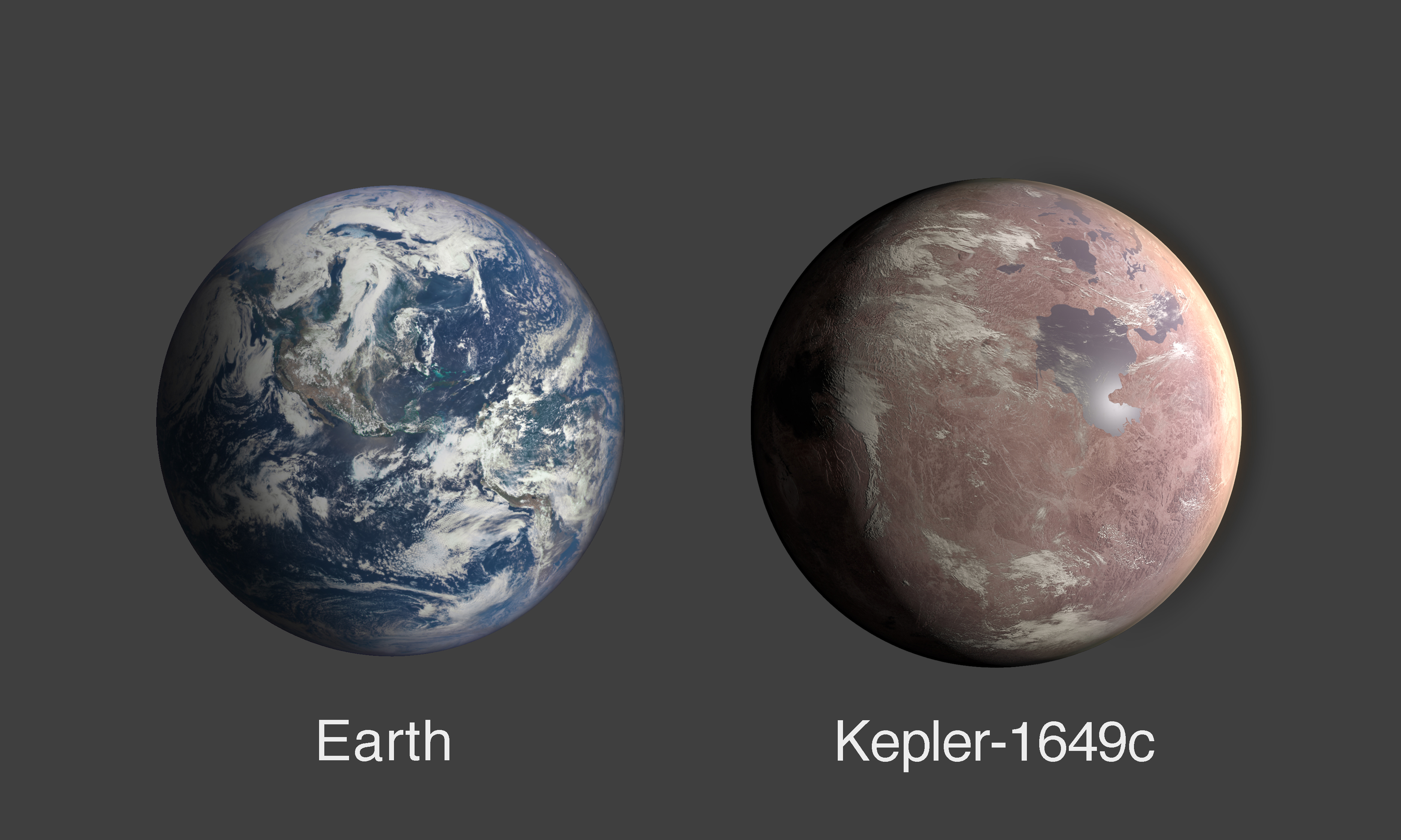

In 2020, scientists cross-referencing Kepler’s catalogs with fresh measurements from NASA’s TESS satellite rediscovered Kepler-1649c, an Earth-sized planet that had been previously misclassified due to an algorithmic error.

The planet, located 300 light-years away, is just 1.06 times larger than Earth and receives roughly three-quarters of the starlight our planet gets from the Sun.

Its estimated temperatures place it firmly within the range compatible with liquid water. For astrobiologists, Kepler-1649c immediately became one of the most compelling Earth analogs ever detected.

However, behind the excitement lies a sobering reality. Among the 2,662 planets Kepler found, only 16 reside in the habitable zone. Many of these worlds are tidally locked, with one side permanently scorched by daylight while the other is frozen in eternal darkness.

Others resemble mini-Neptunes, with thick hydrogen atmospheres capable of crushing any potential oceans beneath pressures too intense for life.

Meanwhile, red dwarf stars—despite their prevalence—are notoriously volatile, frequently bombarding their planets with intense ultraviolet radiation that can strip atmospheres entirely.

Complicating matters further, astronomers currently lack the instruments required to definitively analyze the atmospheres or surface compositions of these distant planets.

Even on the most promising candidates, questions about temperature, chemistry, and habitability remain largely unanswered.

And yet, the statistics derived from Kepler’s full dataset remain electrifying: astronomers now believe that one in five Sun-like stars hosts an Earth-sized planet with temperatures suitable for life.

With hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy, that number translates to billions of potentially habitable planets—just in the Milky Way.

Beyond Earth-like worlds, Kepler also unveiled cosmic oddities that challenge our understanding of planet formation. Gas giants known as “hot Jupiters” appeared frequently, orbiting their stars at blistering speeds.

Super-Earths—larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune—revealed exotic structures ranging from rocky surfaces to volatile gas envelopes.

Lava planets circled their stars so closely that their crusts melted into global oceans of magma. Astronomers also uncovered multi-star systems with planets threading complex gravitational fields, including KOI-5Ab, a planet first flagged in 2009 but overlooked for years.

Newer observations finally confirmed its existence in a three-star system—an extraordinarily rare cosmic arrangement that may reshape theories about how planets form in gravitationally chaotic environments.

Kepler’s mission officially ended in October 2018 when the spacecraft ran out of fuel. Engineers issued a final “goodnight” command, closing the chapter on one of NASA’s most consequential missions.

And yet, Kepler’s legacy is only beginning. Its enormous archive continues to be mined by astronomers armed with new techniques, powerful computers, and next-generation telescopes.

Foremost among these is the James Webb Space Telescope, designed to peer into the atmospheres of distant exoplanets with unprecedented clarity.

Webb’s observations will target several of Kepler’s most intriguing finds, potentially revealing whether any of these alien worlds harbor water, clouds, or even chemical signatures that hint at biological activity.

The deeper scientists dive into the Kepler archive, the clearer the message becomes: our galaxy is far stranger, more diverse, and more promising than we ever imagined.

In the years ahead, Kepler’s long-retired instruments may yet help answer one of humanity’s oldest questions—whether life exists beyond Earth—and perhaps point us toward worlds that are not only habitable, but even more suited to life than our own.

News

Shocking Discovery Beneath Machu Picchu: What They Found Will Change History Forever!

A previously unknown chamber beneath Machu Picchu reveals Inca water channels and ritual spaces, reshaping our understanding of the site….

Harmony Grove’s Memory Music Box: Orphan Boy Discovers Magical Link to the Past

On a quiet Saturday afternoon in the small town of Harmony Grove, Oregon, 12-year-old Caleb Porter wandered the streets, his…

Louisiana Governor’s Outrageous Suggestion: Trump as LSU’s Next Football Coach?

Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry suggests Donald Trump should help pick LSU’s next football coach, sparking outrage. ESPN analyst Ryan Clark…

Outrage at the Ballpark: Karen’s Epic Meltdown Over a Home Run Ball Leaves Fans in Shock!

A father and son’s joy over a first home run ball turns chaotic when a woman aggressively demands it, sparking…

Shocking Body Cam Footage Reveals DHS Agent’s Disturbing DUI Arrest – You Won’t Believe What He Said!

DHS agent Scott Deisseroth is arrested for DUI with children in the car, revealing shocking behavior on body cam footage….

Canada Strikes Back! Furious New Ads Target Trump as Tensions Escalate

Canada launches a bold ad campaign directly challenging Trump’s policies and asserting national economic independence. Prime Minister Carney emphasizes self-reliance…

End of content

No more pages to load