Despite standing under 5’6”, Hollywood’s golden-age actors like Mickey Rooney, Edward G. Robinson, and Charlie Chaplin became iconic stars, defying studio expectations and audience assumptions.

For decades, Hollywood sold America an illusion. The dream factory that created the world’s most iconic stars wasn’t just hiding scandals, affairs, and addictions—it was hiding inches.

Studios lied about height, built trenches on sets, and ordered custom elevator shoes by the dozen. Contracts quietly demanded shorter co-stars.

And when audiences looked up at their heroes, they never realized that many of Hollywood’s leading men were much smaller than they appeared.

Take Mickey Rooney. At just 5’2”, he was the shortest leading man of classic Hollywood, yet he towered at the box office. From 1939 to 1941, he out-earned Clark Gable, Cary Grant, and Gary Cooper. MGM found a way to turn his size into magic.

With his boyish face and manic energy, Rooney became the eternal teenager Andy Hardy in a 16-film series that grossed nearly $1.9 billion in today’s money. Americans, crushed by the Great Depression, saw Rooney’s optimism and felt lighter.

But when World War II ended, Rooney came back a decorated soldier with a Bronze Star, and Hollywood didn’t know what to do with him.

Casting notes read the same phrase again and again: “height problem.” Romantic leads looked absurd. Rooney once joked he needed a wooden box to kiss his co-stars.

By the 1950s, his salary had collapsed from $5,000 a week to scraps. Yet his size saved him again. In gritty postwar roles—like a broken-down boxing trainer—he earned Oscar nominations.

In 1979, Francis Ford Coppola cast him as a retired jockey in The Black Stallion. For once, being small was perfect. The film grossed $40 million and earned Rooney another Academy nod.

Sammy Davis Jr. stood just 5’3”, but no one looked bigger on stage. Born into a family of performers in 1925, Sammy was dancing in shiny little shoes at age three. By the 1940s, nightclubs rejected him for being too young, too Black, and too short.

Then, a car crash cost him an eye. Most would have quit. Sammy doubled down. He sang like Sinatra, played drums like Gene Krupa, and danced until audiences gasped. When people whispered about his size, he turned it into a punchline.

“I’m a one-eyed Negro Jew. And on top of that, I’m short,” he’d say, before silencing the laughter with a song. In 1964, Broadway producers worried he’d look ridiculous towering under a Swedish co-star in Golden Boy.

Sammy worked harder, training his punches and demanding lighting that stretched his shadow across the stage. The show sold out before opening night, and Sammy won a Tony nomination.

By 1968, Las Vegas hotels that once refused him were paying $35,000 a night. His contracts demanded integrated audiences and the best suites.

He released over 50 albums, starred in 38 films, and raised three-quarters of a million dollars for Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement in a single year. Sammy proved that height mattered only if you let it.

James Cagney never stood taller than 5’5”, though Warner Brothers swore he was 5’9”. His military records told the truth, and so did his biographers.

Yet Cagney became the embodiment of screen power. In The Public Enemy (1931), his coiled energy exploded when he smashed a grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face—a scene so raw it still shocks today.

Directors filmed him from the knees up, or put him on crates. But Cagney’s force made everyone else look smaller.

He fought studio bosses, too. In 1936, he literally climbed onto a golf cart to look Jack Warner in the eye while demanding equal pay.

He got it. His stature shaped some of Hollywood’s greatest scenes. In White Heat (1949), he darted through an oil refinery, climbing ladders and catwalks during massive explosions.

A taller man could never have fit in the shots. The movie made back its $1.3 million budget in six weeks. By the time AFI named him the eighth greatest male star in 1999, no one cared how tall he was.

Edward G. Robinson, at 5’5”, looked nothing like a movie star. Born Emanuel Goldenberg in Bucharest, he spoke only Yiddish and Romanian when he arrived in America at age 10.

Casting directors saw a round-faced immigrant kid, not a gangster. Robinson transformed himself in the mirror, perfecting a menacing lip curl and a hammer-hard voice.

In Little Caesar (1931), he played Rico Bandello, a ruthless mob boss, and critics said his frame “fills the screen with menace.” Warner Brothers lied about his height, filming him from low angles and printing that he was 5’9”. It didn’t matter.

The $280,000 picture earned $1.5 million during the Depression. Robinson became one of Warner’s top earners, demanding script approval usually reserved for Gable.

Offscreen, he joked that his small size made him a safer USO performer—“a 5’5” target gives the Nazis half a chance.” But behind the humor was grit: he gave over $250,000 to anti-fascist causes and built an art collection worth $3.5 million.

Then there was Charlie Chaplin, whose 5’5” frame became the foundation of his genius. His “Tramp” costume—tiny hat, tight coat, oversized trousers—made him look even smaller, like a child in adult clothes.

Yet once he moved, his physical comedy was unstoppable. Studies at Columbia University found that audiences watching Easy Street had 38% higher stress reactions when tall bullies threatened him.

Viewers instinctively rooted for him. His height made him relatable, even huggable, in a way no six-foot hero could match.

Buster Keaton, the “Great Stoneface,” also stood at 5’5”. His small build gave him a low center of gravity, which allowed him to survive stunts that would have killed taller men.

In Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928), a 4,000-pound building facade crashed down, missing his head by just three inches. He survived only because he’d marked an exact spot on the ground.

By the 1920s, he was earning $3,500 a week—nearly $60,000 today—and running his own studio. When sound killed his career, TV revived it, showing a new generation that small men could take the biggest falls and get back up.

Peter Lorre, Burgess Meredith, Lou Costello, and Alan Ladd—all under 5’6”—each left their own mark. Lorre, at 5’5”, terrified audiences in M and haunted Hollywood for three decades. Meredith became unforgettable as the Penguin in Batman and Rocky Balboa’s gruff trainer.

Lou Costello, just 5’5”, turned his size into laughs beside Bud Abbott, selling $85 million in war bonds during WWII.

Alan Ladd, famously paired with 4’11” Veronica Lake, required trenches and platforms so taller co-stars wouldn’t overshadow him.

In Shane (1953), he stood against towering mountains, his slight figure whispering the film’s most famous line: “There’s no living with a killing.”

Hollywood once believed size made a star. But these men proved the opposite. In a town of illusions, they showed that talent, presence, and grit could stretch taller than any measuring tape. The studios could lie about the inches—but on screen, audiences always saw the truth.

News

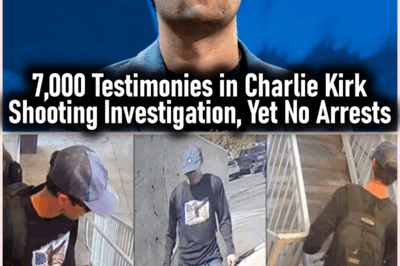

FBI Releases New Images of Charlie Kirk Shooting Suspect as Investigation Intensifies

The FBI has released new photos of a person of interest in the fatal shooting of conservative commentator Charlie Kirk…

Stephen A. Smith condemns anyone celebrating Charlie Kirk’s assassination, praises Yankees for tribute

Stephen A. Smith publicly condemns anyone celebrating the assassination of conservative commentator Charlie Kirk, calling such behavior “despicable” and praising…

Elon Musk pledges $1M to murals honoring Ukrainian refugee murdered in North Carolina

Billionaire Elon Musk has pledged $1 million to fund murals honoring Iryna Zarutska, the 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee fatally stabbed on…

Real Housewives of Salt Lake City Star Mary Cosby’s Son Arrested on Charges of Assault, Trespassing and More

Mary Cosby’s son, Robert Cosby Jr., was arrested on September 6 in Salt Lake City on charges including assault, criminal…

FBI Receives Over 7,000 Tips in Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation, No Arrests Yet, Utah Governor Confirms

Utah Governor Spencer Cox emphasized the importance of public cooperation, urging anyone with photos, videos, or information to come forward…

Shaun White and Nina Dobrev Call Off Engagement After Five-Year Romance

The couple, who began dating in 2019 and got engaged in October 2024, shared a highly publicized relationship filled with…

End of content

No more pages to load