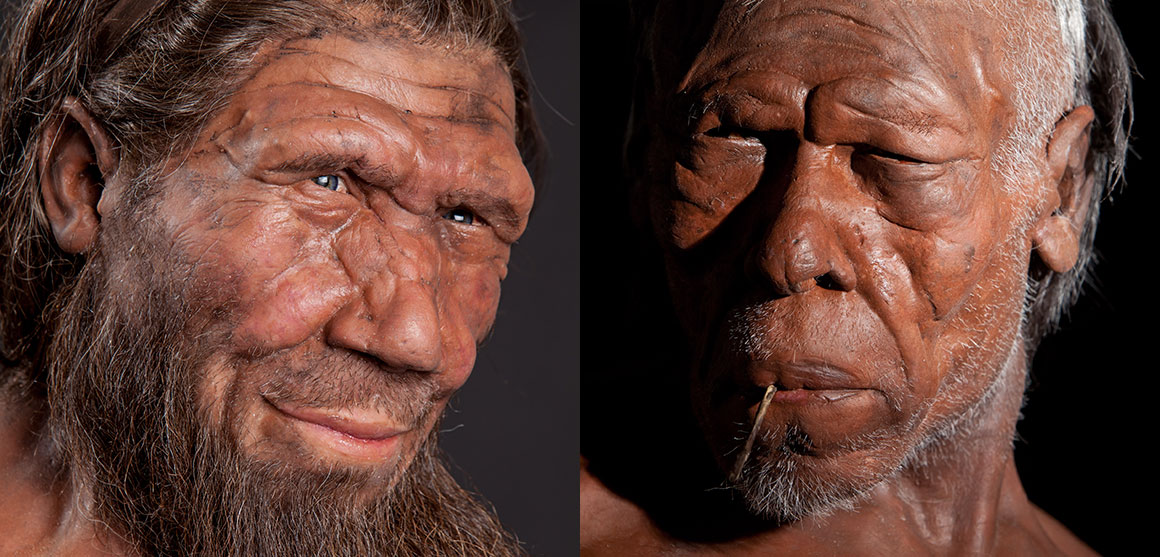

Scientists reveal that Neanderthals aren’t truly extinct—they live on in modern human DNA. Ancient interbreeding with Neanderthals has shaped our immunity, traits, and genetic legacy.

In a groundbreaking revelation that challenges everything we thought we knew about human evolution, scientists have uncovered an astonishing truth about Neanderthals: they didn’t simply vanish; they left a genetic legacy that continues to influence us today.

For decades, the prevailing narrative painted Neanderthals as a primitive offshoot of the human family tree that succumbed to extinction around 40,000 years ago. However, recent advancements in ancient DNA analysis have unveiled a much more complex and intriguing story.

The official account has long suggested that Neanderthals were a cold-adapted species, evolving in the harsh climates of ancient Europe.

Their robust physiques and distinctive features led many to believe they were an inferior group, destined to be replaced by the more sophisticated Homo sapiens.

Yet, new research reveals a different picture—one where Neanderthals were not a dead end but rather a vital part of our own ancestry.

Scientists have recently scanned the DNA of Neanderthal remains dating back 40,000 years, uncovering what can only be described as a genetic echo—a remnant of their existence that survived their supposed extinction.

This discovery suggests that Neanderthals were not just a separate species but part of a complex web of human evolution that involved migration, interbreeding, and cultural exchange.

The narrative surrounding Neanderthals has been rewritten by the findings from ancient DNA analysis. Researchers have discovered that Neanderthals were not confined to Europe as previously thought.

Archaeological evidence indicates that their tools and remains have been found across vast distances, from Siberia to the Middle East, suggesting a much broader habitat than the narrow confines of Europe.

This revelation raises critical questions about their origins and the paths they took across the globe.

Genetic studies indicate that the ancestral lines of Neanderthals and modern humans diverged approximately 500,000 to 600,000 years ago.

However, rather than a simple split, the relationship was more akin to a braided river, with multiple interactions and exchanges between various human groups.

For instance, a significant discovery in a Spanish cave revealed early Neanderthal remains that shared mitochondrial DNA with Denisovans, another enigmatic group of ancient humans.

This finding shattered the simplistic view of human evolution, illustrating that Neanderthals were intertwined with other human species from the very beginning.

Further DNA sequencing has shown that Neanderthals were not a monolithic group. Instead, they comprised distinct populations with unique genetic signatures that evolved separately for tens of thousands of years.

Yet, these groups were not isolated; they engaged in extensive migrations and exchanges across Eurasia.

Ancient highways, created by shifting climates, facilitated these movements, allowing Neanderthals to interact, mate, and share resources with one another.

The Denisovans, initially known only through a few bone fragments, have emerged as a crucial part of this narrative. Genetic evidence indicates that Neanderthals and Denisovans coexisted and even interbred, producing hybrid offspring. One remarkable discovery involved a teenage girl whose DNA revealed a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, providing undeniable proof of these interactions.

As Homo sapiens began to migrate out of Africa around 50,000 years ago, they encountered Neanderthals in their territories.

This meeting was not simply a matter of competition; it marked the beginning of a profound exchange that would ultimately lead to the integration of Neanderthal DNA into the modern human genome.

Today, individuals of non-African descent carry between 1% and 2% Neanderthal DNA, a testament to the intermingling of these two species.

The implications of this genetic inheritance are far-reaching. Neanderthal genes have been linked to various traits in modern humans, including immune responses and adaptations to different environments.

While some of these genetic contributions have proven beneficial, others may have introduced vulnerabilities, such as increased risks for certain diseases.

This complex interplay of genetics highlights the dual nature of our inheritance from Neanderthals—a blend of advantages and challenges that continues to shape our health today.

Despite the evidence of their integration into our genetic makeup, the question remains: what ultimately happened to the Neanderthals? The answer lies in a combination of factors that led to their gradual decline.

As populations shrank due to environmental pressures and inbreeding, their genetic diversity diminished, making them increasingly susceptible to diseases and less adaptable to changing conditions.

The arrival of Homo sapiens, with their larger social networks and advanced technologies, further compounded these challenges, leading to a slow unraveling of Neanderthal communities.

Interestingly, the story of Neanderthals is not one of complete extinction but rather transformation. They did not simply disappear; they became part of the broader human experience, woven into the fabric of our genetic history.

This revelation prompts us to reconsider the narrative of human evolution, recognizing that the tale of Neanderthals is intricately linked to our own.

So, as we delve deeper into our genetic past, we must ask ourselves: Are Neanderthals truly gone, or do they continue to gaze back at us from within our very cells?

This astonishing discovery not only reshapes our understanding of human history but also invites us to reflect on the complex relationships that have defined our species for millennia.

News

Propulsion Expert Unveils Disturbing Truths About UFO Encounters!

U.S. Air Force personnel reported mysterious lights and a metallic craft in England’s Rendlesham Forest, sparking one of the most…

Shocking Revelation: The Ethiopian Bible Unveils Jesus’s Hidden Teachings After His Resurrection!

Newly uncovered texts in the Ethiopian Bible reveal hidden teachings of Jesus after His resurrection that have been absent from…

Is It Here? The Mysterious Interstellar Object 3I Atlas Set to Make History in Just 48 Hours!

Interstellar object 3I Atlas is speeding toward the sun, exhibiting bizarre anomalies that challenge everything scientists know. Experts speculate it…

AI Unveils Terrifying Secrets Beneath the Puerto Rico Trench: What Lies in the Depths?

AI exploration reveals shocking secrets in the Puerto Rico Trench, overturning decades of oceanographic assumptions. Deep-sea life and geological activity…

Unveiling the Science Behind Our Favorite Monsters: Are They More Than Just Fiction?

Scientists and cultural experts explore why monsters like Godzilla, zombies, and dragons captivate our imagination and reflect human fears. …

Ancient Calendar of Doom Discovered at Göbekli Tepe: Are We Headed for Another Catastrophe?

AI deciphers 12,000-year-old Göbekli Tepe carvings, revealing an ancient calendar that tracks cosmic catastrophes. The V-shaped symbols suggest prehistoric humans…

End of content

No more pages to load