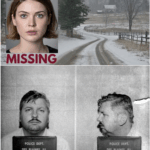

On a dead-end Texas backroad in 1987, the hum of a radio was the last witness to a girl’s vanishing.

Seventeen-year-old Claire Weaver stepped into the dusk and never came back.

The road swallowed her name.

The town swallowed the questions.

A forgotten well behind the Weaver family home.

A small red diary that refused to stay buried.

This is the story the past begged to tell.

This is the echo that won’t fade.

Listen closely.

The dark remembers.

And it speaks when you least expect it.

The Last Evening

The evening of October 13, 1987 drifted over Redwater like a slow, amber tide.

Claire Weaver’s radio was alive with static and summer songs that didn’t realize the season was gone.

Her room smelled faintly of cedar and lilacs.

There was a pamphlet on the desk about a college in Dallas, her name written in pencil along the margin.

Her father, Jacob, was in the garage, tightening a stubborn bolt that refused him peace.

Her mother, Ruth, was in the kitchen, slicing apples with the care of a ritual she had built around worry.

And Claire—the girl with a laugh like a windchime in a storm—stepped out the back door to breathe.

She had been talking to someone.

At least, that’s what the neighbor said.

A figure leaning by the fence.

A voice that carried like a warning trapped in a joke.

The radio hummed.

The screen door clicked shut.

The quiet after was not an empty quiet, but a quiet that feels like a thought that forgot to finish.

By morning, the room was a shrine.

The bed made.

The diary missing.

The driveway dust undisturbed.

And in Redwater, silence arrived like the first frost.

It crystallized everything.

It did not melt.

A Town That Learns to Whisper

Redwater did not like to shout.

It preferred secrets, kept like quilts folded in cedar chests.

People asked questions the way they ask for sugar—politely, with a soft smile, hoping the answer would taste sweet.

But the taste around Claire’s name was metal and rain.

Detective Roy Bannon arrived three days later.

Retired now, but then he was the man you called when a rumor turned its face away from the light.

He walked the backroad each morning at six.

He read the ditches.

He listened to dogs.

He asked what the wind might know when it moves through fields and forgets to leave a footprint.

He found nothing.

No tire marks.

No calls from payphones.

No boyfriend with a hidden temper that town gossip could gift a motive.

What he found instead was a gap.

The kind that sits between two words when a person wants to confess but cannot press their tongue to truth.

The Weaver family kept the porch light on for three months.

Then a year.

Then ten.

At some point the bulb gave up.

No one noticed.

It was that kind of surrender.

The Call That Woke the Past

Decades later, the tip-line rang at 2:14 a.

m.

The operator had been playing solitaire, half-asleep, when the voice arrived.

It was a breath first.

Then a scrape.

Then words that sounded like they had splinters in them.

Behind the Weaver house.

The well.

Concrete poured and forgotten.

Look for the red diary.

The line went dead as if the past had only rented courage for a minute.

Roy Bannon sat in his kitchen, elbows on oak, listening to his old clock refuse to tick right.

He had retired twelve years earlier.

He had a bad knee.

He had a good memory.

He also had a promise he had made to a mother’s eyes in 1987, eyes that looked like a prayer that had given up but stayed kneeling anyway.

He dialed a number with fingers that had learned arthritis the hard way.

By sunrise, there was a truck rolling down the Weaver driveway.

By noon, there was a crew.

By afternoon, there was a jackhammer refusing to blink.

Neighbors came and stood with their hands in their pockets and their mouths closed.

Redwater learned to watch like this.

It was a town built for watching.

And the past was ready to be seen.

Concrete That Doesn’t Forget

Beneath the elm behind the Weaver home, there had been a well once.

Old.

Stones stacked like teeth.

Rumor said Jacob had it sealed.

He didn’t like the way it looked.

Didn’t like the way kids might find gravity as a dare.

In the late eighties, a man named Earl poured the concrete.

He did it on a Sunday morning when church bells were making promises in another language.

He did it hastily.

And he did it thick.

The slab was clean.

Too clean.

It had the kind of rightness that makes you suspicious.

When the jackhammer bit, Redwater flinched.

Dust lifted from memory like it had been waiting its turn.

Roy Bannon watched the edges of the hole, the way the circle grew until it felt like a mouth that intended to speak.

Cracks spidered across the surface.

A chunk broke and a smell rose that had no place in daylight.

It was the smell of closed things, trapped things, and time itself gone sour.

Someone turned away.

Someone else stayed because turning away felt like running.

Then there was a sound, soft as a secret.

A container scraped stone.

A thin ribbon, an elastic scrap.

Red.

They drew out a small book, swollen with damp and years.

A diary.

Red leather.

Its edges bled color.

Its pages swelled like a drowned chest.

And when they opened it, the first words begged not to be read.

Roy read anyway.

He had come this far for a truth.

Truth rarely dresses politely.

A Girl Who Wrote in the Dark

The diary’s entries began in June and ended in October.

The handwriting slanted like a road that refused a straight path.

Claire wrote about the radio and the smell of rain when it hits dust.

She wrote about a boy who wanted to be seen only when he wasn’t himself.

She wrote about a secret she didn’t ask for.

On September 22, she wrote a name and crossed it out so hard the paper tore.

On October 1, she wrote the word well and drew a circle next to it, then shaded it until the paper bruised.

On October 12, she wrote a sentence that Roy would carry like a stone for the rest of his life.

He said we don’t tell anyone because it’s nothing.

But nothing feels like drowning when you can’t breathe.

The next page was blank except for a smear that could have been ink or rain or something else.

The last page had a pressed flower.

It was brittle.

It broke into a powder of memory when it met air.

Roy closed the diary.

He stared at the hole.

He tried to imagine Claire’s last evening.

He failed.

Imagination can be cruel when truth is still deciding whether it wants to be believed.

The Cassette and the River

In the same slab, beneath the diary, there was a tin.

It had been wrapped in cloth.

The cloth had rotted into thread and dust, but the tin had the stubbornness of old things that refuse to surrender.

Inside was a cassette tape.

No label.

Just faint scratches like a map where the cartographer lost interest.

They cleaned the cassette.

They found an old player.

They fed silence into the machine and asked it to sing.

What came out was a war between static and confession.

A girl’s voice first.

Claire’s.

Test, test, okay.

Then a pause that felt like a staircase leading down.

A boy’s voice followed.

You can’t keep me in that book, Claire.

His laugh was not laughter.

You think writing makes it not happen.

You think a page is a wall.

But walls crack.

Then a scrape.

Then something like a prayer caught in wire.

Claire again.

I’m not a wall.

I’m just telling the truth.

He said stop saying truth like it’s a knife.

He said truth cuts people who don’t deserve it.

The tape ended with water.

River or rain.

Everyone standing around the player heard their own version of guilt in that sound.

Roy pressed stop like it would undo anything.

It didn’t.

Names That Refuse to Stay Hidden

Redwater was careful with names.

It had learned that names are heavier than stones and sharper than glass.

But names are also keys.

They open rooms you forgot were locked.

Roy went to the high school yearbook from 1987.

He let his finger walk the rows like a tired detective might walk the edges of an old wound.

He paused at a smile that didn’t reach the eyes.

He paused at a boy who worked summers with Earl pouring concrete.

He paused at someone who had sat beside Claire in Chemistry, who had carved initials into the underside of the bleachers where gum and secrets live.

No one in town wanted to say his name aloud.

So Roy did.

He said it like a question asked by someone who already knows the answer.

He went to a house with a white fence that never quite stayed white.

He knocked on a door that had learned to avoid visitors.

The man who opened it had gray in his hair and lines around his mouth that looked like apologies that never found their words.

He didn’t run.

He didn’t deny.

He just closed his eyes and said, no more wells.

Roy did not put handcuffs on him that day.

He put the tape on the table.

He put the diary beside it.

He put the town between them like a witness that couldn’t lie anymore.

And the man began to speak.

The Confession No One Was Prepared to Hear

He said it wasn’t supposed to be a forever act.

He said it was supposed to be a pause.

He said they argued.

He said she had a way of making silence feel like the wrong choice.

He said she told him Redwater wasn’t big enough for both truth and the version of himself he wanted to be.

He said the well was old and easy and there.

He said concrete keeps secrets like a pastor keeps confessions, neat and anonymous and eternal.

He said he had help.

He said Earl poured on a Sunday.

He said Jacob asked questions and accepted answers the way a father accepts what makes the world simpler.

He said none of this was supposed to be the ending.

He said he didn’t mean to write a period.

He meant a comma.

He said the river took the tape and gave it back.

He said he didn’t know why the diary stayed red in the dark.

He said he didn’t know why the flower didn’t survive.

He said he dreams about the hum of a radio and wakes up believing he’s still in the garage listening to a bolt lose its stubbornness.

He said he can’t remember the last time he loved the sound of rain.

Roy listened.

Detectives learn how to make space for the worst parts of human architecture.

He didn’t say forgiveness.

He didn’t say punishment.

He said, write it down.

Write it all down.

Because sometimes writing isn’t a wall.

Sometimes writing is a window.

Redwater’s Quiet Cracks Open

News travels in towns like Redwater the way sparks travel in dry grass.

Fast.

Hungry.

Ready to invent.

But this time, the invention wasn’t necessary.

There was a tape.

There was a diary.

There was a well.

There was concrete that didn’t forget even when people begged it to.

Ruth stood on the porch and held the diary like it was both her daughter and not.

Jacob sat in the garage and turned a bolt for an hour without needing it to move.

Neighbors brought casseroles and apologies.

The church opened its doors and tried to teach the town how to breathe again.

A camera crew came.

They asked questions with round eyes and fast hands.

Roy answered carefully.

He refused to turn a girl into a headline.

He refused to turn a confession into a spectacle.

He said something simple instead.

He said, the past speaks when we listen.

And the town, for once, listened.

The Silence After the Noise

The well was emptied.

Earth returned to the mouth of memory.

The slab was gone.

The elm stood quiet and old.

The river kept moving like it always does, uninterested in the way people assign meaning to its water.

Roy stood there and realized retirement is a word we use when we want to pretend the past also retires.

It doesn’t.

It waits like a phone with a number you never forget.

He thought of Claire.

Not the rumor of her.

Not the tape.

Not the diary.

But the girl who wrote about the smell of rain on dust.

Who pressed flowers between pages and believed the world could be kept.

He thought of truth.

He thought of wells.

He thought of concrete and Sundays and the way towns invent ways to survive themselves.

He went home and put the cassette in a drawer.

He put the diary in a box.

He wrote a memo that read, case closed.

Then he crossed out closed and wrote, told.

Because the past had been given a voice.

Because the town had been given a window.

Because the girl had been given back, not in flesh, but in the way a name returns to a place that never should have lost it.

News

They Tried to Hide This Place Forever

In a world filled with secrets and hidden treasures, there lies a place so enigmatic that it seems to have…

The Mysterious Journey of the Nautilus: A Quest for the North Pole

In the heart of the Arctic, where the icy winds howl and the sea is a vast, frozen expanse, lies…

The Chiefs’ Trade Dilemma: A Countdown to the NFL Deadline

As the clock ticks down to the 2025 NFL trade deadline, the Kansas City Chiefs find themselves at a critical…

How Darrell Waltrip Helped Redefine Safety in NASCAR After 2001

Introduction: The Day That Changed NASCAR Forever February 18, 2001 — a date no NASCAR fan will ever forget. The…

“The Day Darrell Waltrip Thought He’d Di3 on the Track – A Forgotten NASCAR Near-Tragedy”

Introduction: The Forgotten Brush with Death in NASCAR History Every NASCAR fan knows Darrell Waltrip — the legend, the champion,…

Darrell Waltrip Finally Breaks Silence: Dale Earnhardt’s Haunting Last Words Moments Before the Deadly Daytona Crash 😢🏁**

Introduction: The Day NASCAR Changed Forever February 18, 2001 — a date etched forever in the heart of NASCAR fans….

End of content

No more pages to load