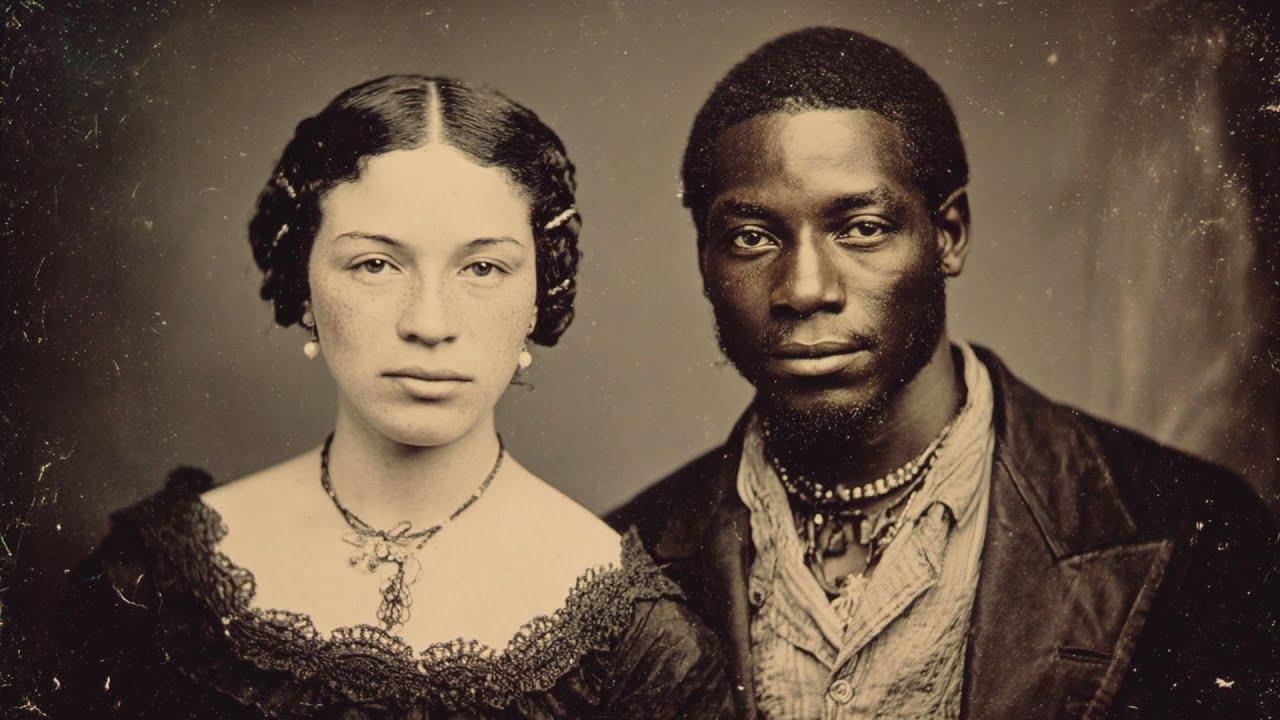

“She Left Her Plantation, Her Husband — and Her World: The Mystery of Louisiana’s Missing Bride” 🌾

The story begins on a suffocating August evening in 1847.

The Dumont plantation, one of the largest sugar estates in southern Louisiana, glowed beneath the lantern light of a summer ball.

Guests danced, the orchestra played, and the mistress of the house — young Eleanor, barely twenty-two — floated among them in a silk gown, smiling the way women are taught to smile when their hearts are breaking.

Her husband, Charles Dumont, was twice her age, a man of immense wealth and cruelty, known for his iron fist and restless temper.

To outsiders, he was a gentleman; to those who worked his land, he was a tyrant.

But that night, as the guests raised their glasses, Eleanor was already planning her escape.

Hidden behind the sugarcane fields, at the edge of the bayou, a man waited — a man she had met in secret for months.

His name was Samuel, a field hand who had once belonged to Charles but had fled into the swamp after a brutal beating.

For weeks, rumors spread that someone was helping him, feeding him, hiding him.

No one suspected the master’s wife.

The affair had begun in whispers — a few words exchanged through a cracked door, a stolen glance at dusk.

Samuel was everything Charles was not: quiet, thoughtful, and kind.

He had built her a small wooden charm — a carving of a mockingbird — which she kept hidden in her corset.

It became her talisman, a symbol of the freedom she longed for.

And on that August night, with the sound of violins echoing through the plantation house, she slipped away into the dark, leaving behind a half-empty ballroom and a world she could never return to.

By morning, the news had spread.

The mistress was gone.

Her carriage was missing.

A servant claimed to have seen her walking toward the cane fields before dawn, barefoot, her white dress dragging through the mud.

Charles Dumont went mad with rage.

He sent search parties into the bayou, offered rewards to bounty hunters, even summoned local militias.

“Bring her back,” he reportedly screamed, “or bring me her body.

”

For weeks, they searched.

Dogs tracked faint scents through the swamp but lost them near the old Spanish trail.

Some said they found a piece of silk tangled in the reeds; others swore they heard voices at night — a woman crying, a man whispering her name.

Then, just as quickly as she had vanished, the trail went cold.

The swamp swallowed its secrets.

What happened next has been the subject of legend, speculation, and folklore for nearly two hundred years.

Some say Eleanor and Samuel reached freedom, traveling north through the Underground Railroad under false names.

Others believe they drowned trying to cross the Mississippi, their bodies claimed by the river.

But the most chilling version — whispered among the locals of St.

Martin Parish — says Charles found them.

According to an old family journal discovered in 1923, Charles Dumont received an anonymous letter two months after Eleanor’s disappearance.

It contained only one line: “They are in the cypress woods.

” The following week, locals reported hearing gunshots near Bayou Teche.

A fisherman later found a woman’s shoe caught in the roots of a tree — small, white, and embroidered with pearls.

Charles never spoke of it again.

But the morning after those gunshots, he ordered an unmarked grave dug behind the sugar mill.

Years later, workers claimed the plantation was haunted.

They told stories of hearing a woman’s footsteps on the gallery after midnight, her dress brushing the floor, her voice calling softly into the dark.

“Samuel,” she would whisper.

And then — silence.

The legend became known as The Bride of the Bayou.

But recently, historians have uncovered documents suggesting that Eleanor and Samuel may have actually survived.

Letters found in a trunk belonging to an abolitionist family in New Orleans mention a “young woman of breeding” traveling with a man “of African descent” under the names Eliza and Thomas Green.

The letters describe their arrival at a safe house near Natchez and their plan to move north by steamboat.

If true, it would mean they escaped the South entirely.

One line from the letter stands out: “She said she would rather die in freedom than live as another man’s possession.

” It was signed only with initials — E. D.

Whether she lived or died, Eleanor Dumont’s disappearance became more than a scandal — it became a symbol.

A rebellion against the cruel logic of her time.

Her choice to love a man society deemed beneath her wasn’t just a personal act; it was a revolution disguised as romance.

In a world built on ownership, she refused to be owned.

Today, the old Dumont plantation is nothing but ruins.

The house burned down in 1896, the land overgrown with wild grass and ghosts.

But locals still tell her story.

Tour guides point toward the cypress trees where the moonlight turns the water silver and say, “If you listen close, you can hear them — the bride and her love, still running.

In the stillness of Louisiana’s swamps, time has a way of blurring truth and legend.

Maybe Eleanor and Samuel never escaped.

Maybe their bones rest beneath the murky waters that hid their love for centuries.

But maybe, just maybe, they made it — two souls who defied the impossible, vanishing not into tragedy, but into freedom.

Because some disappearances are not about loss at all.

Some are about becoming untouchable — beyond history, beyond hatred, beyond the chains of the world that tried to keep them apart.

And somewhere, in the hush of the bayou, the mockingbird still sings for them — the vanished bride of 1847, and the man who dared to love her.

News

😱 They Said It Could Never Sink… Then the Ocean Proved Them Wrong: The Last Days of the Bismarck 🚢💀

Germany’s Pride, Britain’s Revenge — The Shocking, Hour-by-Hour Death of the Bismarck 🕯️ The Bismarck wasn’t just a ship. It…

💔 He Was Called “The Boy With the Lion Face” — The Untold Agony Behind Rocky Dennis’s Mask 😢

The Beautiful Monster: How One Boy’s Face Shattered America’s Idea of Beauty 😭 Before the cameras ever rolled, before…

🐻 “Scientists Just Revealed the Titanic’s REAL Fate — What They Found at the Wreck Will Leave You Speechless”

🌊 “The Truth About the Titanic Disaster Finally Emerges — And It’s Far Darker Than We Ever Imagined” April…

🐻 “The Secret Neil Armstrong Took to His Grave — The Truth Behind the First Man on the Moon 😱”

🚀 “The Moon Landing’s Hidden Truth: What Haunted Neil Armstrong Until His Final Days” It was July 20, 1969….

🐻 “Alcatraz Escape Mystery FINALLY Solved in 2025 — The Shocking Truth About What Really Happened to the Anglin Brothers 😱”

“After 63 Years, The Alcatraz Escape Case Is Finally Closed — The Hidden Evidence That Confirms the Impossible” On…

“SHe Tried to Sell her Bike Soher Mom Could Eat — What the Bikers Discovered Next Left Them in Tears 😢”

“When a Hungry Girl Approached the Bikers With His Old Bicycle, They Never Expected the Secret She Was Hiding” They…

End of content

No more pages to load