In the early spring of 2019, Boston-based photograph restorer Marcus Chen received what he thought would be a routine commission — a faded glass negative from 1907 depicting a little girl with her doll.

The request came from Elellanena Hartwell, a woman who had just inherited her great-grandmother’s estate in Connecticut. Among the brittle letters, dust-choked portraits, and cracked photo albums, there lay a single photograph her family had avoided for generations.

“It’s haunted us,” Elellanena confessed over the phone. “Every person who’s looked at it closely says the same thing — something about it feels wrong.”

Marcus had heard stories like that before. People project emotions into old photographs; they mistake damaged emulsion for ghosts, pareidolia for presence. But when he lifted the fragile glass plate into the light of his restoration lamp, something in the image stopped him cold.

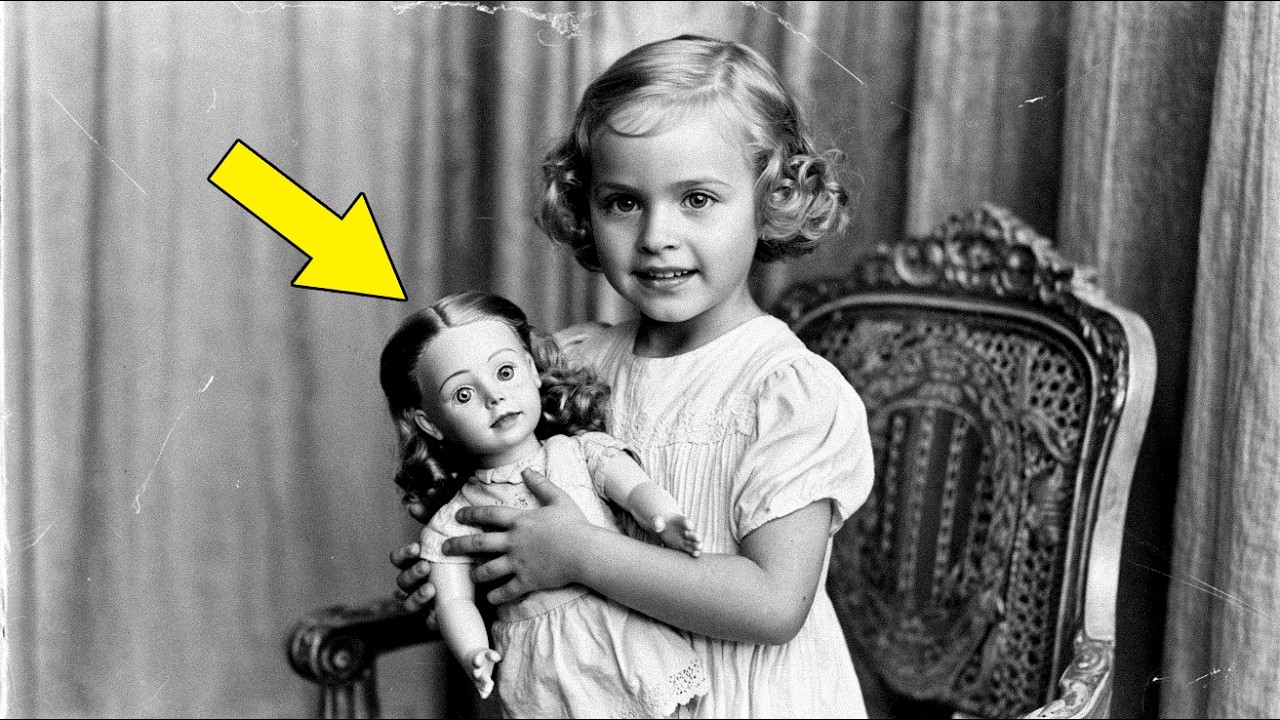

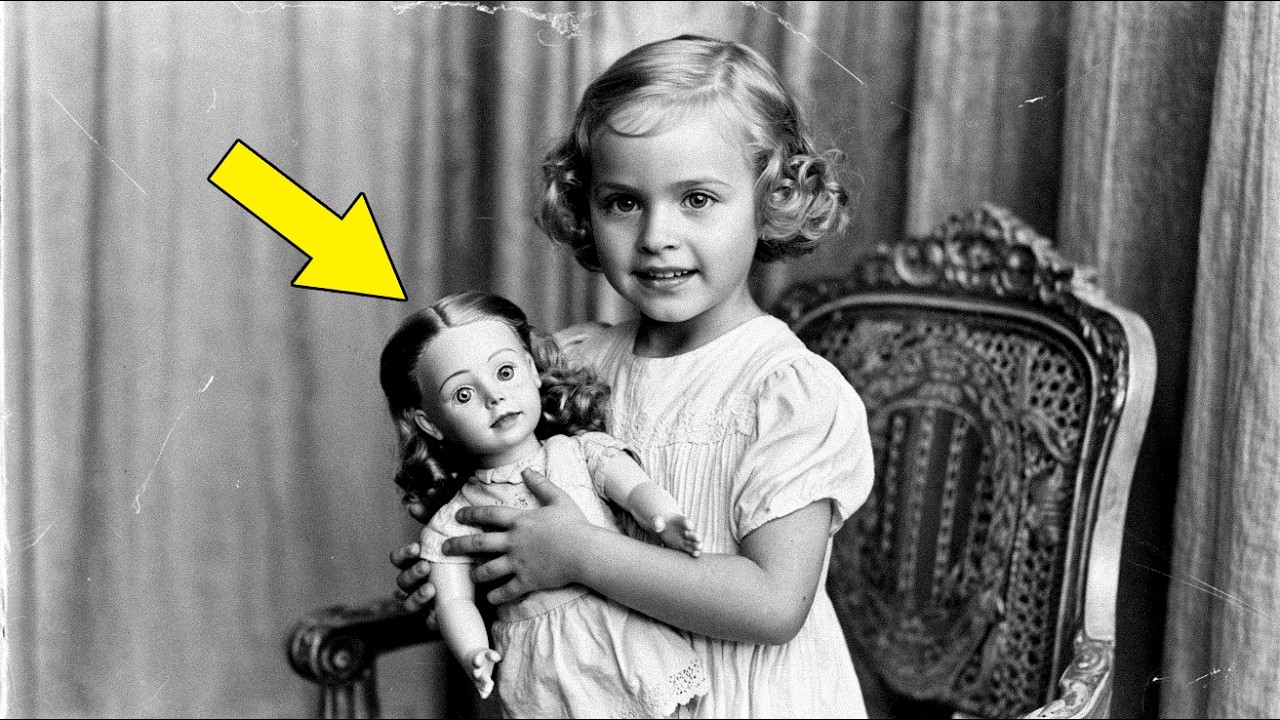

The photograph showed a girl, about eight years old, standing in a photographer’s studio. She wore a white lace dress, her curls arranged with maternal precision. In her arms, she clutched a porcelain doll — a beautiful object of the era, with painted lips and glass eyes.

The girl smiled brightly, radiantly. But the longer Marcus looked, the more his comfort ebbed away.

The doll’s gaze wasn’t right.

The Restoration

Two weeks into his restoration, Marcus enhanced the image at high resolution. What emerged made him freeze mid-keystroke.

The doll’s eyes, which should have been painted to face forward, appeared — in the untouched glass negative — to be turned ever so slightly toward the girl. Not dramatically. Just enough to be unmistakable once seen.

He checked his calibration, rescanned the negative, and compared it to the print. The effect persisted. In the print, the oddity was subtle. In the negative, it was glaring.

That night, Marcus called Elellanena.

“Do you know the girl’s name?” he asked.

“Her name was Catherine,” she replied after a pause. “Catherine Anne Hartwell. My great-grandmother’s sister. She died in 1908, a year after that picture was taken. She was nine.”

Marcus had restored countless portraits of the dead, but this one unsettled him. The longer he stared at the enhanced image, the more he felt as if he was intruding — as if he had opened a door that was meant to remain closed.

The Physician’s Journal

A week later, his research led him to a name: Dr. Edmund Mercer, a physician in rural Connecticut who had treated a child named Catherine Hartwell in 1908. In the Yale historical archive, Marcus met Dr. Patricia Walsh, who presented Mercer’s journal — three volumes of meticulous, clinical handwriting.

March 14, 1908:

“Called to the Hartwell residence to examine young Catherine, age 9. Fever reported. Child appears healthy. No elevated temperature at present. Displays peculiar episodes of distraction — staring at things not present.”

March 15:

“Fever resolved, yet episodes continue. The child now stares for hours at her doll. When the mother removes it, the child becomes hysterical.”

Mercer’s tone was rational, detached — the voice of science confronting the unexplainable. Over the next weeks, he documented Catherine’s decline. No infection. No trauma. Just hours of staring.

April 2, 1908:

“Found Catherine deceased. Eyes open. Directed toward the doll resting beside her. No signs of illness or injury. Cause of death uncertain. The family requests the doll be buried with her.”

Marcus read in silence. The journal’s final line chilled him:

“Some mysteries, I have come to believe, are not meant for the medical sciences to solve.”

The Grave

Riverside Cemetery was quiet when Marcus found Catherine’s headstone. Simple inscription, 1899–1908. Beneath her name, carved in delicate relief, was the unmistakable face of a doll.

It wasn’t typical. Children’s graves from that period were adorned with angels, flowers — not toys. Yet there it was, a porcelain face etched in stone. And its eyes, though carved, seemed to erode differently from the rest of the headstone, as if worn smooth by countless fingers tracing the gaze.

The caretaker, a man named Robert, recalled the legend. “People still visit,” he said. “Leave dolls, old toys, sometimes pictures. We clear them away, but they always come back.”

In the county records office, Marcus found something stranger. Catherine’s burial record bore a later note, dated June 1923:

“Grave exhumed at family request. Contents confirmed. Doll present as recorded. Grave resealed.”

No reason given.

The Pattern Emerges

When Marcus shared his findings online, a historian named Sarah Mitchell contacted him. She specialized in early 20th-century childhood mortality — and recognized the pattern immediately.

“There were others,” she said, spreading old photographs across the café table. All were from 1900 to 1910. All showed children posing with dolls or toys. In each, when studied closely, the object’s angle of gaze appeared subtly wrong — not toward the camera, but toward the child.

Within eighteen months of each photograph being taken, every child was dead.

Most of the deaths were listed as “fever” or “sudden illness.” None explained. In every case, the child’s family destroyed or buried the object with them.

Sarah’s notes described “episodes of peculiar focus” — children staring at their toys for hours as if mesmerized.

Marcus felt cold realization creep in. “You’re saying these photographs… show something?”

“I’m saying,” Sarah replied, “that the same thing keeps happening — and no one can explain it.”

The Mother’s Letter

Then, Elellanena called again. She had found a letter hidden among her great-grandmother’s belongings, dated May 1925. Written by Catherine’s mother, Margaret Hartwell.

“My Catherine was a good child. But in 1908, the doll became something else. She would stare for hours, unblinking, as if it were speaking to her. I sought doctors and clergy, but none could help.

When she died, I buried the doll with her, believing the bond would end. But it did not. We heard tapping in her room, saw shadows that moved without light.

In 1923, we opened the grave. The doll was untouched, perfect. Its eyes followed me. I knew then that we had disturbed something that should never have been disturbed.

Whoever finds this — know that my daughter did not die of illness. She followed whatever looked at her through those painted eyes.”

Marcus read the words aloud to Sarah, both of them silent afterward. It was the testimony of a woman who had seen the impossible and never recovered from it.

The Decision

Marcus never released the enhanced images. He completed two restorations: one for the Hartwell family archive, and another that he destroyed.

He deleted his backups, burned his notes, and stopped taking commissions for a time. “Some things,” he told Sarah in their last call, “aren’t meant to be studied too closely. Some images look back.”

A month later, Elellanena informed him the family had moved Catherine’s grave to a sealed crypt — no visitors allowed, no records public. “We just want it to end,” she said.

Marcus understood. But sometimes, he still dreamed of the photograph — of the child’s smile, and the doll’s tilted gaze frozen forever in silver nitrate. He would wake with the same thought repeating in his mind:

What did they see when they opened that grave?

The Photograph Today

The original glass negative remains in the Hartwell estate, sealed in a climate-controlled archive. Few have seen it. Fewer still claim to have examined it closely.

Those who have describe an inexplicable discomfort — the sense that the doll’s gaze changes depending on where you stand, as though aware of your observation.

Marcus Chen, now retired, refuses to discuss the case publicly. In one brief interview, when asked whether he believed in the supernatural, he only replied:

“I believe photographs capture more than light.”

Epilogue: The Pattern Persists

In recent years, several online researchers have noted other photographs from the same era — similar poses, similar expressions, and always, always a toy. None of the images are verifiably linked, yet the pattern endures.

And once you’ve seen it, you can’t unsee it: the subtle angle of the doll’s head, the faint trace of movement where no movement should be.

Maybe it’s coincidence. Maybe it’s pareidolia — the human mind’s need to find faces in shadows. But somewhere in Connecticut, beneath a sealed crypt, lies the doll that started it all.

It has been over a century since Catherine Hartwell smiled for the camera in 1907.

Her photograph remains unchanged — yet those who look too long swear the doll’s gaze shifts still, ever so slightly, toward the girl beside it.

And if you stare long enough…

you might see it turn toward you.

News

They ABUSED the beautiful slave, BURIED HER ALIVE — but at midnight, she made THEM ALL REGRET IT

In the oppressive heat of a Georgia summer in 1857, a young enslaved woman named Pearl endured the unimaginable. Violated,…

Dallas Cowboys Star Marshawn Kneeland Dead at 24 After Self-Inflicted Gunshot Wound — Inside His Final Hours, His Mother’s Tragic Death, and the Signs Everyone Missed

The NFL world has been rocked to its core. Just three days after celebrating a touchdown under the bright lights…

What really is going on with Browns QB Shedeur Sanders, lack of details around his back injury

Something strange is happening in Cleveland — and it’s got the entire NFL world whispering. Shedeur Sanders, the highly scrutinized…

Donna Jean Godchaux DEAD at 78 — The Heartbreaking Farewell to the Voice That Bridged Elvis, Soul, and the Grateful Dead 💔🎤

The world of music is reeling after the death of Donna Jean Godchaux, one of the most soulful and influential…

Why Metallica ACTUALLY chose Rob Trujillo… and were they WRONG about it?

When Metallica announced in 2003 that Rob Trujillo would replace Jason Newsted as their new bassist, the decision divided fans…

🐿️ Their Relationship Didn’t Last Long, But Their Song Lives On—The Untold Heartbreak Behind Steve Perry’s ‘Oh Sherrie’ And The Love Story That Shook Rock History! 💔🎤 – Perry’s Passion Immortalized, Sherrie Swafford’s Secret Side, And The Ballad That Outlived Their Romance! 🎶

The Heartbreaking Story Behind “Oh Sherrie”: A Love That Inspired a Classic In the world of rock music, few songs…

End of content

No more pages to load