In a remarkable turn of events, a family portrait that had long concealed a significant figure has found its rightful place at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met).

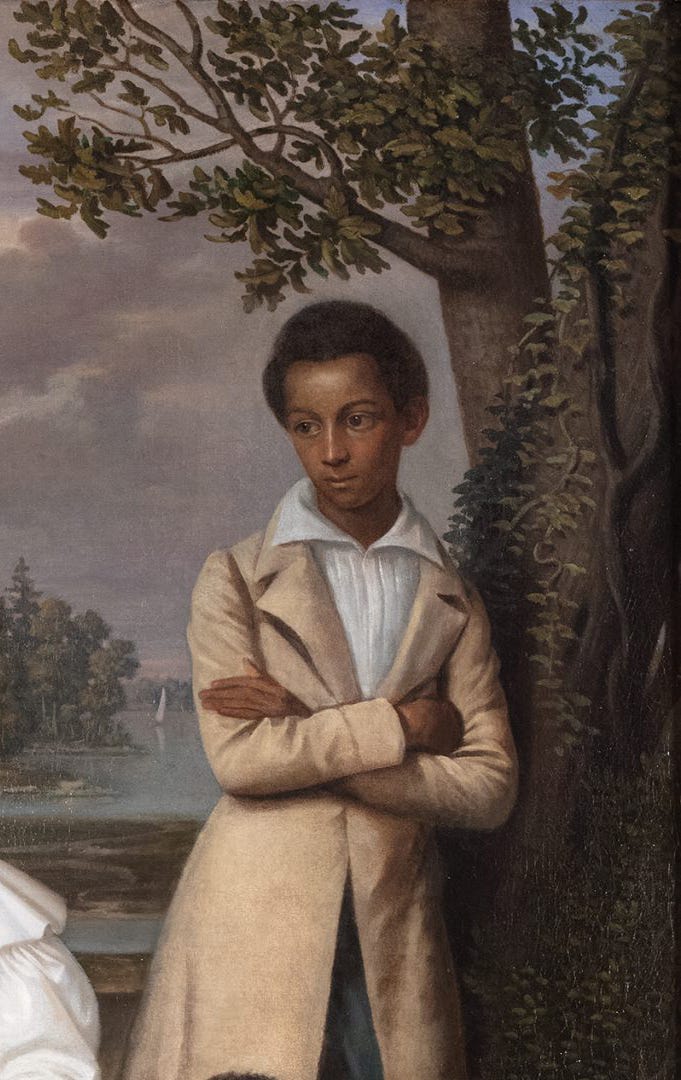

This painting, which depicts three white children in a seemingly idyllic setting, originally featured a fourth figure—an enslaved child named Bélizaire—who had been painted out.

The acquisition of this portrait not only highlights the historical erasure of Black figures in art but also sheds light on the complex narratives surrounding slavery in America.

The story of the portrait begins with Jeremy K. Simien, an art collector and advocate for the representation of African descent in American history.

His journey commenced when he stumbled upon the painting in an auction record.

Despite its unsigned nature, Simien recognized stylistic similarities to the work of renowned portraitist Jacques Amans.

However, what captivated him most was the haunting knowledge that the enslaved child had been obscured from view.

Simien’s quest for the truth intensified when he discovered another auction record indicating that the painting had been altered to hide the child.

“The fact that the boy was covered up haunted me,” he recalled, igniting his determination to uncover the identity of the erased figure.

The narrative surrounding the portrait is rooted in the family history of Eugene Grasser, a descendant of the white children depicted in the painting.

According to family lore, the Grasser family had a favored enslaved boy who was originally included in the portrait but later painted out for reasons unknown.

Eugene’s mother, Audrey, inherited the portrait and kept it stored away for decades until she donated it to the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) in 1972.

Despite the intriguing family history, NOMA placed the painting in storage for 32 years instead of exhibiting it.

This decision reflects a broader pattern of institutional neglect regarding artworks that feature people of African descent.

Mia L.Bagneris, a professor of art history and Africana studies at Tulane University, remarked, “This is what the work looked like when NOMA acquired it. And you can clearly see the spectral outline of the figure.”

The museum’s justification for not displaying the painting stemmed from the lack of information about the artist and the sitters, highlighting a systemic issue in art institutions that often overlook the significance of works featuring marginalized individuals.

In 2004, NOMA decided to sell the painting at auction, where it was purchased by an antiques dealer for $6,000.

After restoration, the previously hidden figure was revealed, exposing Bélizaire to the world once more.

Simien, after years of searching, finally acquired the painting in 2021, bringing it back to Louisiana.

Recognizing the importance of the piece in relation to his heritage, Simien sought to further restore the painting to its original intention.

To achieve this, he enlisted the help of Craig Crawford, a conservator who aimed to remove layers added in previous restorations.

The goal was to uncover the painting’s true essence while honoring the memory of Bélizaire.

Simien’s mission was not only to preserve a piece of art but also to reclaim a lost narrative that had been buried for generations.

With the goal of uncovering more about the enslaved child’s identity, Simien collaborated with Katy Shannon, a researcher specializing in the history of enslaved individuals.

Together, they traced the Grasser family lineage and discovered that the boy depicted in the painting was likely Bélizaire, a mixed-race child who was around 15 years old at the time the portrait was painted.

Census records from the 1830s confirmed that Bélizaire was indeed associated with the Frey family, who commissioned the portrait.

He had been sold into the Frey household along with his mother, Sally, in 1828.

This discovery illuminated the reality of Bélizaire’s life—a stark contrast to the serene domesticity portrayed in the painting.

While he appeared to be valued as a family member, the underlying truth was that he could be sold at any moment, reflecting the precarious existence of enslaved individuals.

The painting’s history of erasure speaks volumes about the societal attitudes of the time.

After the death of Frederick Frey, Bélizaire was sold to Evergreen Plantation on Christmas Eve in 1856.

Sometime after this sale, he was painted out of the portrait, a decision likely influenced by the racial dynamics of the era.

The turn of the century saw the implementation of Jim Crow laws, which further entrenched racial segregation and the devaluation of Black lives.

The act of painting out Bélizaire can be seen as a reflection of these societal changes, where the presence of Black individuals was systematically erased from historical narratives.

Craig Crawford’s analysis of the painting revealed that the cover-up was executed with lighter colors to match the skyline, leaving behind traces in the craquelure pattern.

This evidence suggested that the alteration occurred around the turn of the century, aligning with the historical context of racial segregation and erasure.

In the spring of 2023, the painting’s journey took a significant turn when a dealer representing Simien contacted a curator at The Met.

The curator was captivated by the story behind the painting and recognized its importance in representing enslaved individuals in a realistic and respectful manner.

The museum acquired the portrait for its permanent collection, marking a pivotal moment in the recognition of Black figures in art history.

The acquisition of this painting is not just about restoring a work of art; it symbolizes a broader movement toward acknowledging and preserving the narratives of marginalized individuals.

As the curator noted, “In the past, we weren’t asking all the right questions. We weren’t looking for depictions of enslaved people in a more naturalistic way.”

The portrait of Bélizaire stands as a testament to the necessity of revisiting historical narratives and ensuring that all voices are heard.

The story of Bélizaire and the family portrait encapsulates a significant chapter in the ongoing struggle for recognition and representation of Black individuals in American history.

Through the tireless efforts of collectors, researchers, and art institutions, Bélizaire’s identity has been restored, and his narrative reclaimed.

This journey from erasure to recognition serves as a reminder of the importance of acknowledging the complex histories that shape our understanding of the past.

As museums and institutions continue to confront their histories, the acquisition of Bélizaire’s portrait at The Met represents a critical step toward inclusivity and acknowledgment of the contributions of enslaved individuals to American culture.

The painting not only honors Bélizaire’s life but also challenges us to reflect on the broader implications of representation in art and history.

It is a call to action for future generations to seek out and celebrate the stories that have long been hidden in the shadows.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

News

Travis Tritt’s Georgia Ranch – Southern Rock Rebel’s Horses, Music, and Country Living

Nestled deep in the picturesque Georgia countryside lies a sanctuary that perfectly embodies the spirit of country music legend Travis…

At 62, Julian Lennon Finally Breaks Silence On May Pang

In a recent revelation, Julian Lennon, the eldest son of the legendary John Lennon, has finally addressed the long-standing and…

She Utterly Hated Cloris Leachman, Now We Know the Reason Why

In the world of Hollywood, where personalities often clash and friendships can be as fleeting as a film’s box office…

Maggie Baugh FINALLY Responds to Affair With Keith Urban

In the glitzy world of Hollywood, where love stories often play out like fairy tales, the relationship between Nicole Kidman…

The SECRET Michael Jackson Shared with His BROTHER — and Only Came to Light After His Passing

In the world of music and entertainment, few names resonate as deeply as Michael Jackson. Known as the “King of…

Dog Keeps Bringing Strange Rocks From Woods, Owner Looks Closer And Realizes They Were…

In a rural corner of Oregon, a golden Labrador named Murphy embarked on a daily adventure that would lead to…

End of content

No more pages to load