I think it became fashionable to hate

me. I get it. I wasn’t cool. Isn’t it

time we stopped hating Phil Collins? For

a guy who topped charts, sold out

stadiums, and played both sides of Live

Aid in one day, Phil Collins has taken

more punches than most pop legends. Over

the years, he became an unlikely

punching bag, mocked by critics,

dismissed by rock purists, and even

insulted by artists half his age. Over

the years, he’s had a few enemies of his

own, and he didn’t hold back. From

awkward snubs by his childhood heroes to

grunge icons who called for his head,

these are the moments where Collins drew

the line, and some of the names may

surprise

you. Let’s dive in. Pink Floyd. I was

()

never a big Floyd fan. Phil Collins has

never pretended otherwise. In interviews

stretching across decades, he’s made it

clear that Pink Floyd just didn’t do it

for him, especially in their early

years. I saw them at the marquee with

Arnold Lane,” Collins recalled in a 2014

interview with documentarian John

Edgenton, but they just didn’t do it for

me. He admitted that he was more of an

early Yes fan and respected bands like

Jethro Tull, but never connected to

Floyd’s heavy spaced out sound. Even as

Genesis was being grouped alongside

Floyd in the burgeoning Prague rock

movement of the 1970s, Collins rejected

the comparison. I was in a band that was

always put in the same box as that lot,

but I never felt that we actually were

in the same box, but we probably were.

The tone is classic Collins,

self-deprecating, but pointed. Pink

Floyd were the moody mystics. Collins

was the drummer who wanted a tune you

could hum in the car. While Collins

mostly kept his critiques light, Roger

Waters did not. In a 1992 Musician

magazine interview, Waters unleashed one

of the most brutal takedowns in rock

diplomacy. I seem to always wind up

attacking poor Phil Collins. He’s

symptomatic of an awful lot of um what’s

wrong with the music industry. He might

disagree and so might his fans, but the

feeling I get is that he’s pretending to

be a songwriter or a rock and roller.

It’s an act. That’s why it’s

unsatisfying. For Waters, Collins

represented everything he hated about

1980s pop, slick production, chart

friendly melodies, emotional shallowess.

That might seem ironic considering Pink

Floyd sold out stadiums and released The

Wall, one of the most over-the-top

theatrical productions in rock history.

But for Waters, artistry was about

confronting society’s demons. Not

writing a radio hit like Sudio. At its

core, this wasn’t just a clash of

personalities. It was a clash of musical

ideologies. Pink Floyd believed in

crafting immersive sonic experiences

driven by themes of alienation, war,

madness, and institutional decay. Phil

Collins, especially post Genesis,

favored emotional accessibility. His

songs were about heartbreak, divorce,

regret, and occasionally gorillas

playing drums. Both sold millions of

records. Both had legions of fans, but

one viewed the other as self-important

and daer, while the other dismissed his

counterpart as commercial fluff. In

Colin’s words, “I liked what I heard

from Floyd when I came across it by

accident, but I never really sit down

and listen to them. That line alone says

everything about the dynamic. Floyd was

the band you had to prepare yourself

for. Collins was the guy who showed up

on the radio whether you wanted him or

not. It’s impossible to talk about this

feud without considering the Genesis

Pink Floyd parallel. For years, Peter

Gabriel’s theatrical Genesis was seen as

Floyd’s peer in Prague ambition. When

Gabriel left, Collins took over and led

the band into shorter, poppier

territory. Critics howled. Record sales

soared. Roger Waters, still steeped in

concept albums and political allegory,

probably saw Collins as a sellout. A

musician who turned Prague rock into pop

candy. Collins, meanwhile, didn’t seem

to care much. Waters is a bit of a

grouch, Collins once quipped in a now

infamous fan forum comment. But

Gilmore’s a lovely, lovely guy. A

perfect summary. Collins admired the

music, but didn’t want the moodiness.

Floyd took themselves seriously.

Collins, despite being a perfectionist,

never took himself too seriously. Some

of the tension came from an off-hand

remark Collins made about Floyd being a

bit boring. Though he later clarified, I

may have said that I think their music

was boring at a time when I was into

more active music. I don’t find them

particularly boring now, but I never sit

down and listen to them. That comment,

while relatively tame, was enough to

earn him a few mocking responses from

Floyd fans and possibly some extra

bitterness from Waters. Both Collins and

Floyd found themselves grouped under the

same genre, Prague Rock, a box that

neither seemed entirely comfortable

with. Collins, in particular, pushed

back hard against the label. As Genesis

moved into pop territory, he tried to

break free from the elaborate stage

shows and 12minute suites. We didn’t

want to write fantasy stories anymore,

Collins said of the postgabriel Genesis

years. We wanted to talk about real

things. Meanwhile, Floyd dug deeper into

their mythos, releasing albums like The

Final Cut and The Division Bell, never

wavering from their commitment to music

as message. And yet, their legacies were

constantly intertwined to the annoyance

of both parties. In later years, the

feud faded into the background, not

quite resolved, but no longer active.

Collins even admitted, “I’ve probably

become more of a Floyd fan in later

years than I was at the time. But make

no mistake, this was never a bromance

waiting to blossom. They didn’t

collaborate. They didn’t tour together.

They didn’t trade respect in liner notes

or festival bills.” Paul McCartney, a

()

hero worship turned sour.

Rock and roll has its fair share of diva

clashes, but the quiet tension between

Phil Collins and Paul McCartney stands

out. Not because it exploded in the

tabloids, but because it started with

one off-hand joke and never really

healed. Collins, like so many of his

generation, grew up idolizing the

Beatles. As a teenager, he even landed a

blink and you’ll miss it appearance in a

Hard Day’s Night as a screaming fan in

the crowd. Years later, after building

his own legacy with Genesis and a wildly

successful solo career, Collins found

himself sharing royal stages, not as a

fan, but as a peer. By 2002, Collins was

a household name. So, when he ran into

McCartney at Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden

Jubilee celebration, he approached him

with genuine admiration and a first

edition of The Beatles by Hunter Davies,

hoping for a signature. Instead, he got

a comment he’d never forget. Oh,

Heather, our little Phil’s a bit of a

Beatles fan. McCartney reportedly told

his then wife. To Collins, it wasn’t

charming. It was patronizing. The kind

of remark that doesn’t sting because

it’s cruel, but because it’s dismissive.

He later told the Sunday Times, “I

thought you [ __ ] You [ __ ] Never forgot

it.” What bothered Collins most wasn’t

just the joke. It was the attitude

behind it. In later interviews, he

claimed McCartney had a way of making

people feel small, saying, “He has this

thing where he makes you feel like, “I

know this must be hard for you because

I’m a beetle.” Collins didn’t need hero

worship. He just wanted respect. Years

later, after Collins recounted the story

in his memoir, Not Dead Yet, McCartney

reached out. According to Collins, the

message wasn’t hostile, but it also

wasn’t warm. I didn’t get flowers. I got

more of a let’s just move on with our

lives to Collins. That wasn’t enough. He

felt McCartney had missed the point. Or

maybe didn’t care to understand why that

moment stung so deeply. What makes this

feud even more striking is how

differently Collins spoke of George

Harrison. After Harrison accidentally

left him off the credits for All Things

Must Pass, he made it up to Collins with

a prank so absurd it ended in laughter.

Collins respected that. It felt

personal, even if it was at his expense.

With McCartney, there was no laugh, no

shared moment, just silence and a quote

that’s haunted Collins ever since.

McCartney was one of my heroes and I

wish I hadn’t met him. It’s not a feud

built on insults or headlines. It’s a

quiet disappointment that never faded. A

childhood idol who in one off-hand

moment revealed a side Collins never

wanted to see. They’ll never trade diss

tracks or Twitter insults. But in

Colin’s mind, that autograph moment said

it all. And he never really let it go.

()

Oasis. They’re just horrible

guys. The feud’s origin goes back to the

early days of Oasis when Noel Gallagher

was still shaping the identity of his

band. With grunge in retreat after Kurt

Cobain’s death, Noel positioned Oasis as

the raw workingclass antidote to what he

called junk food music. That meant

mainstream pop and artists like Phil

Collins. In the 2016 documentary

Supersonic, Noel made his mission

crystal clear. We’re going to get rid of

Phil Collins and Sting, junk food music,

McDonald’s music. We’ve got to get in

the charts and stamp them out. I want

the severed head of Phil Collins in my

fridge by the end of this decade. And if

I haven’t, I’ll be a failure. Even

before Oasis had released definitely

maybe, Nell had already chosen Collins

as a symbol of everything he was

rebelling against. Over the years, Noel

only doubled down. In interviews

throughout the 1990s and 2000s, he

routinely referred to Collins as the

Antichrist and even dragged him into

political commentary. Ahead of the 2005

UK general election, Noel told the

Guardian, “I’ll be voting Labor because

I think it’s morally right.” Another

reason to vote Labor is if the

Conservatives get in, Phil Collins is

threatening to come back and live here.

And let’s face it, none of us want that.

To Noel, Collins represented

overproduced commercial music and

apparently also middle-aged upper class

conservatism.

It didn’t matter whether the political

claims were fair or accurate. They were

brutal and personal. For years, Collins

avoided getting too involved in the back

and forth. But after being called the

Antichrist in interview after interview

and accused of being the reason Oasis

never reached number one, “One with the

jam,” he finally responded. “They’re

just horrible guys,” he said in a TV

interview. They’re rude and not as

talented as they think they are. They

keep having a go at me, which I find

strange. He clarified that he didn’t

hate their music, just their attitudes.

They make good music if you can stomach

their behavior. I like the Beatles, and

what they’re doing is a nod to that. I

liked the music long before I knew what

these guys were doing. But by then, it

was more than a spat. It had become

personal and weirdly iconic. Then came

the moment no one expected. Phil Collins

and Noel Gallagher trapped in the same

Caribbean bar. As Collins recounted in

his autobiography, Not Dead Yet, he was

vacationing with his wife on Mystique, a

private island in the Caribbean, when he

befriended the owners of a tiny local

bar. They joked about Collins doing a

set one night if they brought in a few

musicians. He agreed. But when he showed

up to perform, there they were sitting

in the corner of this tiny bar, Collins

recalled, “Are Null, his wife Johnny

Depp, Kate Moss, and a Labour MP. I

don’t know which one.” Trying to break

the ice, Collins approached Null and

asked if he wanted to join in for a jam.

Gallagher refused. His wife made a

sarcastic comment about Collins’s recent

attempt at guitar music. Collins

admitted, “I retired to the bar,”

feeling not a little embarrassed. Credit

to Kate Moss, though she came over and

apologized for the odd encounter. Then,

as Collins started playing his set, Noel

and his entourage got up and left. If

there were any doubts about how deep the

rift ran, they evaporated on that island

night. The bad blood even reportedly

spilled into the next generation. In a

later interview, Nell claimed that

Collins’s children once mistook Liam

Gallagher for him and confronted him.

“They had a pop at him,” Null said,

saying, “Why are you always having a

furring go at our dad?” When I heard

about it, I thought, “I really hope

someone filmed it.” No reaction. Anyway,

fur Liam and fur Phil Collins and all.

By the 20110s, Noel started to slightly

soften. In an interview with Zayn Low,

he admitted it was a flippant comment

about him being the antichrist. I

probably gave a balanced view of Phil

Collins that day, but what looks good is

the bit about him being the antichrist.

Still, the digs didn’t stop. When asked

about artists he hated, but songs he

liked, he named In the Air Tonight, a

song he admitted to enjoying, but

also in Paradise was Fing S. He did

offer a

backand don’t mind the Gabrielis.

They’ve got some good

tune took over. I wasn’t into that.

Collins later addressed Noel’s political

attack more directly, calling it a

misrepresentation. I don’t care if he

likes my music or not, he said. I do

care if he starts telling people I’m a

wanker because of my politics. It’s an

opinion based on an old misunderstood

quote. By that point, Collins was

nearing retirement. He had wrapped up a

final Genesis tour and publicly stated

he wasn’t planning to tour or release

more music. His focus had shifted toward

writing, family, and his lifelong

fascination with the Battle of the

Alamo, Led Zeppelin, a dream gig turned

()

nightmare. In rock history, some clashes

are loud and chaotic, full of drugs,

guitars, and headlines. Others are

quieter, but somehow more bitter,

lingering like a bad note played at the

wrong moment in front of a million

people. The feud between Phil Collins

and Led Zeppelin falls into the latter

category. It was born out of one of the

most high-profile reunions in music

history, a once-ina-lifetime show that

should have been unforgettable for all

the right reasons. Instead, it turned

into a disaster that both sides would

spend decades blaming each other for.

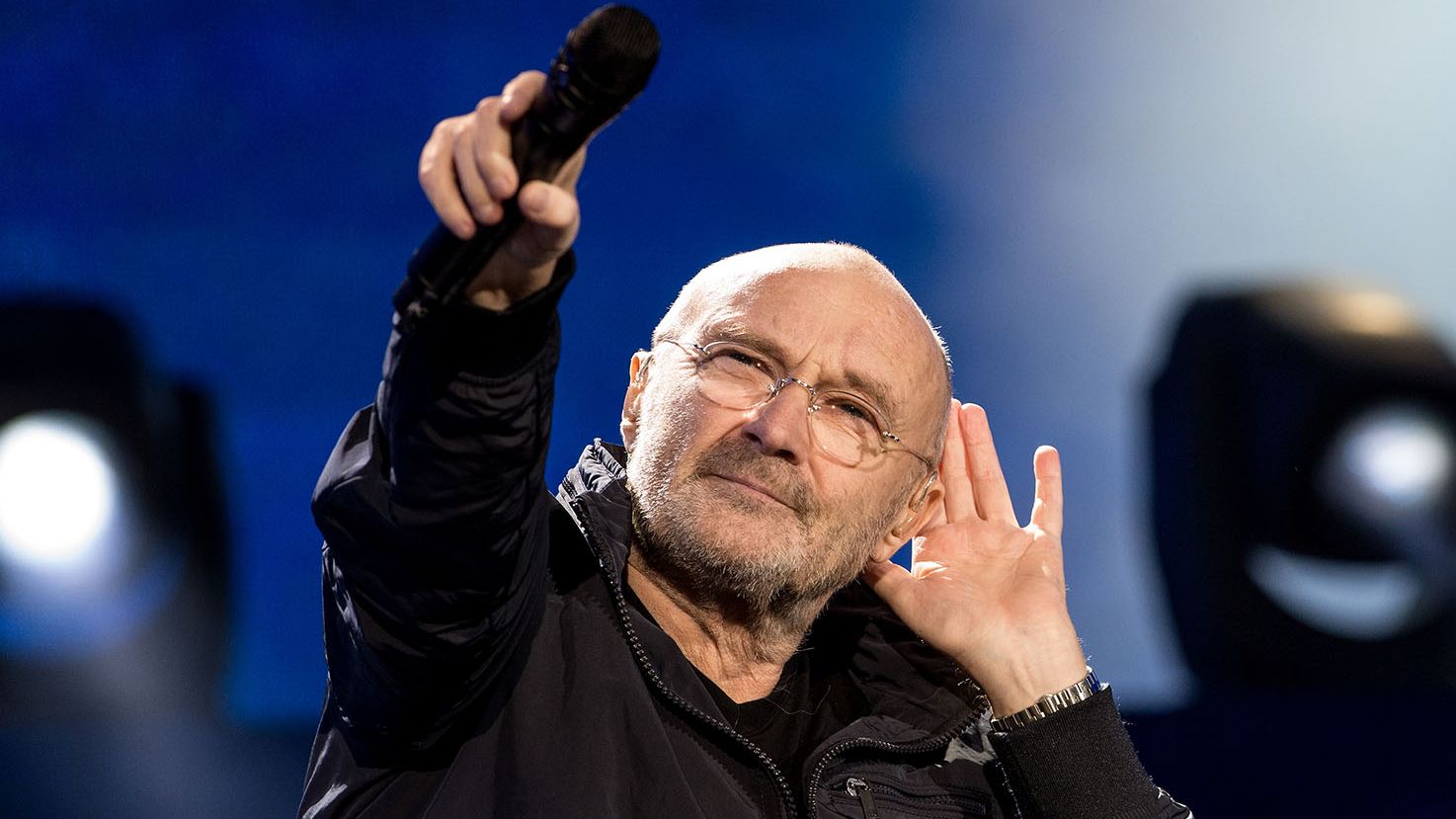

Live Aid wasn’t just another concert. It

was the concert, a global event, a

cause, a spectacle. Organized by Bob

Gelof to raise money for famine relief

in Ethiopia. It brought together the

biggest names in music across two

continents. Phil Collins, riding high as

both a solo star and member of Genesis,

performed at Wembley Stadium in London

before boarding the Concord and flying

to Philadelphia to do it all over again.

This time with Led Zeppelin. But Led

Zeppelin wasn’t Led Zeppelin anymore.

Their legendary drummer John Bonham had

died in 1980. The band broke up soon

after, declaring that they couldn’t

continue without him. For live aid, they

agreed to reunite reluctantly for one

night only. That meant they needed a

drummer, or in this case, two, Phil

Collins and Tony Thompson from Chic.

From the beginning, things were off. In

his memoir, Not Dead Yet, Collins

admitted he thought he’d be playing just

a few songs with Robert Plant and Jimmy

Paige under their own names, not as Led

Zeppelin. He didn’t know the full set

list. He hadn’t rehearsed. His only

preparation was listening to Stairway to

Heaven on

Concord. I arrive and go to the caravans

and Robert says Jimmy Paige is

belligerent. Collins recalled. That

warning wasn’t taken lightly. Once he

met Paige, things soured almost

immediately. When Collins tried to

demonstrate the drum intro to Stairway,

Paige scoffed, “No, it doesn’t go like

that.” It wasn’t exactly a warm welcome.

Despite Colin’s efforts to coordinate

with Thompson and keep things simple,

there was no saving the set. The

performance consisting of rock and roll,

Whole Lot of Love, and Stairway to

Heaven was disjointed, sluggish, and

painfully awkward. Collins knew it in

real time. If I could have walked off

during Stairway, I would have. But

imagine the headlines. Phil Collins

walks out on Led Zeppelin at Live Aid. I

stayed. I mimed. I played air drums just

to get through it. After the show, the

fallout came quickly and publicly. Jimmy

Paige wasted no time throwing Collins

under the bus. We had 2 hours rehearsal,

not even that, Paige told the Times. The

drummer couldn’t get the beginning of

rock and roll. We were in real trouble.

In another interview, he described

Collins as bashing away cluelessly and

grinning during the performance. Even

Robert Plant joined in the passive

aggressive shade. Sitting next to

Collins in a postshow interview with

MTV, he said, “The three of us knew what

we were doing, and everybody else did

their very, very best.” While John Paul

Jones pointed directly at Collins.

Collins, to put it lightly, was furious.

“I got pissed off,” he later admitted.

“Maybe I didn’t know the material as

well as Jimmy wanted, but I wasn’t the

only problem. If you watch the video,

you can see Jimmy dribbling, Robert not

hitting the notes, and me. I’m just

trying to get out of the way. Collins

felt used, underprepared, and blamed,

and he wasn’t about to keep quiet. To

most musicians, playing drums for Led

Zeppelin, even just for one night, would

be a dream. For Collins, it became one

of the worst experiences of his career.

He called it a mistake and a disaster in

nearly every interview since. In fact,

his honesty about how bad it was has

become legendary. It wasn’t amazing to

be there. I have to say they weren’t

very good and I was made to feel a

little uncomfortable by the dribbling

Jimmy Page. Collins told Classic Rock

magazine in 2016. I felt like a spare

part. Ironically, Collins had a deep

admiration for John Bonham, Zeppelin’s

original drummer and considered him a

major influence. He even acknowledged

how impossible it was to fill his shoes.

They should have left it alone. You

can’t replace Bonham with two drummers

and expect it to work. The Zeppelin

performance at Live Aid was so bad that

the band refused to let it be included

on the official Live A DVD release.

Paige, Plant, and Jones made sure it was

left out, as if it never happened. Of

course, the internet never forgets.

Bootlegs and YouTube clips of the set

still circulate, and it’s every bit as

uncomfortable as you’d imagine. Mistimed

cues, missed notes, confused glances

between band members. Collins is clearly

struggling, and so is everyone else. It

was supposed to be a moment of rock

history, a triumphant reunion. Instead,

it became a lesson in what happens when

ego, miscommunication, and lack of

preparation collide on the world’s

biggest stage. In the years since,

Collins has tried to move on, but the

bitterness occasionally resurfaces. In

interviews, he’s painted a picture of a

performance doomed from the start, not

because of malice, but because of poor

planning and misplaced

expectations. Here’s how it is, Collins

said. Robert on his own. Lovely bloke.

Robert with Zeppelin. Something changes.

A dark energy enters the room. It’s like

a nasty strain of alchemy. He didn’t

name Paige directly in that quote, but

he didn’t have to. And while Paige has

expressed some regret about the reunion,

it wasn’t very clever. He told the

Sunday Times, he’s never fully

apologized for throwing Collins under

the bus. If anything, he’s doubled down.

Kurt Cobain, I hate what he stands

()

for. In the early 90s, a seismic shift

was rumbling through the music world.

The leather pants and synths of the 80s

were out. Flannel shirts, angst, and

distortion were in.

Grunge had arrived, and at its helm

stood Curt Cobain, a disheveled punk

with a sharp tongue and a deeply

ingrained disdain for anything he deemed

fake or corporatized, including Phil

Collins. By the time Nirvana’s Never

Mind dropped in 1991, Collins was

already a pop institution. With hits

like In the Air Tonight and Another Day

in Paradise, he’d transcended his

Genesis Prague rock roots and become the

poster boy for soft rock balladry. But

to CooBain, Collins didn’t just

represent old music. He embodied

everything that grunge was rebelling

against. In a 1992 interview with Melody

Maker, CooBain let loose in what would

become one of his most infamous tirades

against another musician. Sitting on top

of the world, Nirvana had just

transformed the music landscape with

smells like teen spirit. Yet Cobain was

already disillusioned with the industry

and ready to name names. You know what I

hate about rock? He asked before

unleashing the verbal napalm. I hate

Phil Collins. All of that white male

soul. I hate tie-dyed t-shirts, too. I

wouldn’t wear a tie-dyed t-shirt unless

it was dyed with the urine of Phil

Collins and the blood of Jerry Garcia.

It was a nuclear level disc, one that

managed to slam Collins, the Grateful

Dead, and the commodification of

counterculture all in one breath. For

Cobain, Collins wasn’t just a musician

he didn’t like. He was the symbol of

everything fake, sanitized, and

commercial. Collins was no stranger to

fame. He’d sold out arenas, won Oscars,

and become a household name. But to Gen

X icons like Cobain, he was the epitome

of dad rock, the friendly face of an

industry that had lost its edge. Collins

wore suits. He was cleancut. He’d

starred in Disney soundtracks and made

records that were too safe for CooBain’s

raw sensibilities. The generational

clash was inevitable. Grunge was about

dismantling the myth of the rock star,

not polishing it with reverb heavy

ballads. Where Collins leaned into

production and emotional polish, Cobain

screamed through distortion pedals with

bleeding sincerity, the two might have

both occupied the top of the charts at

different points, but artistically they

couldn’t have been farther apart. To his

credit, Phil Collins didn’t go full

Gallagher brother with his retaliation.

He never dragged CooBain’s name through

the mud in interviews, but his 1993 solo

album, Both Sides, felt like a quiet

rebuttal. The record was introspective

and minimalist, recorded almost entirely

by Collins himself. Stripped of the big

production gloss he was known for, it

seemed like his attempt to prove that he

too could be raw, emotional, and

musically serious. But to many, the

timing made it look like he was trying

to stay relevant in a world Cobain had

already flipped upside down. Even then,

Collins still came off as the uncle of

rock, as some critics dubbed him.

Kindly, maybe even wise, but out of sync

with the times. For Cobain, hating

Collins wasn’t just about the music. It

was about the system Collins seemed to

represent. He once accused him of being

a symbol of Yepy culture, a clean, safe

figure whose success had been built

within the system Nirvana was trying to

destroy. In Cobain’s view, Collins

wasn’t a threat. He was the

establishment. That’s why his criticism

went so far beyond a bad review. It

wasn’t, “I don’t like his songs.” It

was, “I hate what he stands for.” There

was no chance for the two to reconcile.

Cobain died by suicide in 1994 just as

the grunge movement was beginning to be

absorbed and arguably diluted by the

mainstream. Collins continued to make

music though with diminishing critical

reception and eventually moved into

semi-retirement. Years later, Collins

reflected on the grunge era with a mix

of respect and distance. He praised

Nirvana’s influence on music and didn’t

return Cobain’s personal vitriol. But

make no mistake, he knew how the younger

generation saw him. In one interview, he

quipped, “I think it became fashionable

to hate me. I get it. I wasn’t cool.”

Turns out Phil Collins wasn’t just the

guy behind emotional ballads and iconic

drum fills. He was also quietly keeping

receipts. Behind the scenes, he had

opinions, strong ones. and he didn’t

hesitate to call out the stars he

thought were arrogant, overrated, or

just plain rude. But what do you think?

Was Phil right to speak his mind, or did

some of these grudges go too far? Drop

your thoughts in the comments. Hit that

like button if you didn’t expect that

one name on the list, and share this

video with your favorite music geek.

We’ve got plenty more where this came

from, so make sure to subscribe before

the next feud drops.

News

♐ At 28, Pickle Wheat Finally Admits What We All Suspected

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

Troy Landry JUST Reveals Truth About Pickle Wheat, And It’s Not Good.

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

What Really Happened to Pickle Wheat? Heartbreaking Tragedy From Swamp People

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

The Tragic Accident Happened With Pickle Wheat From Swamp People ?

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

♐ What Really Happened to Pickle Wheat From Swamp People

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

What Really Happened to Pickle Wheat From Swamp People

pickle wheat rises to fame on Swamp People as an actual swamp Queen have enthralled viewers and brought the wild…

End of content

No more pages to load