In nineteen sixty-four, during the filming of

The Sound of Music, a single sound brought chaos

to the set—and nearly destroyed one of the film’s

most iconic scenes. It wasn’t dramatic or tragic.

It was funny—too funny. So funny that no one could

stay in character. Take after take was ruined.

The studio spent thousands trying to fix it, then

chose to bury the story completely. For decades,

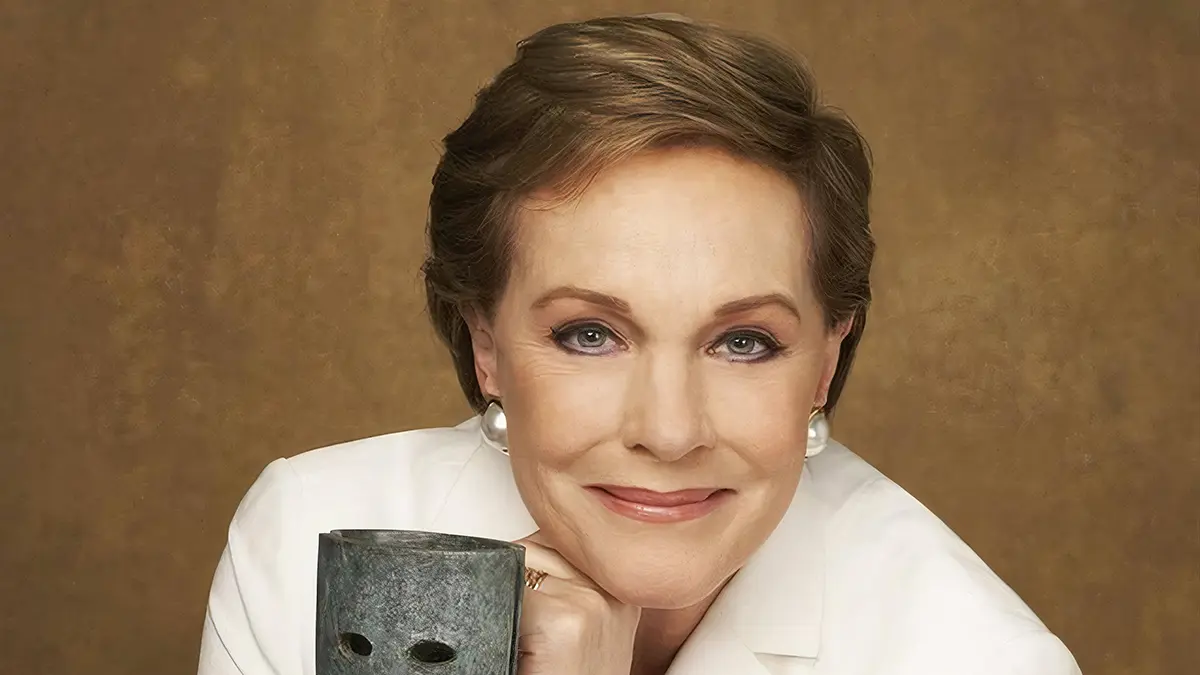

it stayed hidden… until Julie Andrews finally

told the truth on live television. What really

happened in that gazebo? And why did Christopher

Plummer—who hated the film—agree to keep quiet?

Europe Falls in Love with the Story

It all started quietly in the mid-nineteen

fifties. Back in nineteen fifty-six, a

German producer named Wolfgang Liebeneiner

released two films based on Maria von Trapp’s

memoir, The Story of the Trapp Family Singers.

The first was Die Trapp-Familie, and it

was followed by a sequel a year later.

They were low-budget, sentimental, and very

European in tone—but they struck a chord. In

post-war West Germany, people were craving

stories that were heartwarming and full of hope. These two films delivered just that.

Both films turned into box-office gold.

In fact, they were the biggest commercial

film success in West Germany at the time.

The story’s charm didn’t stop there—it spread like

wildfire through Europe and even found an audience

in South America. People across different

languages and cultures connected with the

image of a musical Austrian family standing

up to the Nazis and choosing love over fear.

But when the films were shown to American studios,

the reaction was… not great. To put it nicely,

Hollywood thought the movies looked like a

high school play—too sentimental, too corny,

too “foreign.” Nobody was lining up to

bring the von Trapps to the U.S. screen.

That is, until a man named

Vincent J. Donehue stepped in. Donehue was no ordinary director—he had just won

a Tony Award and had a sharp eye for stories that

could move people. Paramount sent him to scout

out new projects, and he happened to screen the

German Trapp family movies. At first, he

had the same reaction everyone else did:

clumsy and awkward. But then something unexpected

happened. Beneath the low-budget production

and outdated style, he saw something

real. The story had soul. It had heart.

And Donehue said something no

one had dared to say before: “You can’t make this a film. You have to turn

it into a Broadway musical—for Mary Martin.”

That one sentence flipped the switch—and

triggered a chain reaction that would lead

to one of the biggest musicals in history.

But none of it would’ve happened if Maria von

Trapp hadn’t made a very unusual, and some might

say terrible, business decision years earlier…

The Nine Thousand Dollar Deal

Maria von Trapp was no Hollywood insider.

She had no agent, no lawyers looking out for

her. She was just trying to support her family.

So, when German filmmakers came knocking in

the early nineteen fifties asking to buy her

life story, she said yes, for a one-time

payment of just nine thousand dollars.

Now, that might sound small—and it was. Even in

nineteen fifties money, it wasn’t much. Adjusted

for today, it’s about one hundred and four

thousand dollars. Not bad for a quick deal,

but a tiny fraction of what was coming down

the line. And to make things worse—Maria had

unknowingly signed away more than she realized.

Hollywood came calling later, offering to buy

the title of her book, hoping to skip the rights

issues and just adapt a story “inspired” by it.

But Maria stood her ground. She insisted that if

her family’s story was going to be told, it had to

be told truthfully—and in full. No cherry-picking.

By the late nineteen fifties, Mary Martin,

the biggest Broadway star of the era—and her

husband Richard Halliday were determined to

bring the von Trapp story to the stage. But there

was just one problem: no one knew where Maria was. As it turned out, Maria von Trapp was

deep in the jungles of Papua New Guinea,

doing missionary work with Father Franz Wasner,

the family’s longtime musical director. They had

no phones, no internet—just handwritten

letters. And those letters? Maria didn’t

even open them. Every time they arrived at a new

mission post, a pile of mail would be waiting,

often with letters from some couple in

America trying to talk to her about Broadway.

She tore them up. Literally.

Maria wasn’t interested in showbiz. She was

focused on serving people in remote villages,

running clinics, teaching music, and living

simply. Broadway was the last thing on her mind.

But then something unexpected happened.

When Maria and Father Wasner finally returned to

the U.S. by ship, they docked in San Francisco.

And waiting for them at the pier was none other

than Richard Halliday. He handed Maria two tickets

to see his wife perform in Annie Get Your Gun.

Maria agreed to go, probably just to be polite.

But what she saw on that stage blew her away.

Mary Martin was charming, powerful,

and magnetic. Maria was moved—but still had

bad news to deliver. She explained she had

already sold the film rights to the Germans

years ago. That door was technically closed.

Still, she gave the couple

a surprising green light. “You’re welcome to give it

your best shot,” she told them.

That one chance, one casual okay from Maria,

would kick off one of Broadway’s biggest legends.

The Gamble That Paid Off

When producers first got serious about turning Maria von Trapp’s life into

a stage musical, they had a very different plan.

The idea was to mix traditional Austrian folk

songs—like the real tunes the Trapp family sang

in concerts—with just a few new songs to help

tie the story together. Think a little Broadway

flavor sprinkled over old European charm.

But when they approached Richard Rodgers and

Oscar Hammerstein to write just one or two

songs, the legendary duo didn’t hold back.

Rodgers and Hammerstein basically said, “Thanks,

but no thanks—either we write the whole thing, or

we’re out.” They didn’t want their work clashing

with old Austrian ballads. It was all or nothing.

And that moment changed everything.

The producers hit pause. Rodgers and

Hammerstein still had to finish Flower Drum Song,

so the new project was shelved temporarily. But

when they finally returned to the von Trapp story,

they rewrote the entire concept from scratch—with

all original songs. And not just any songs. We’re

talking about classics like My Favorite Things,

Do-Re-Mi, Edelweiss, and Climb Ev’ry Mountain.

Songs that the world still sings today.

Then came opening night—November sixteenth,

nineteen fifty-nine. The curtain rose at the

Lunt-Fontanne Theatre on Broadway with

Mary Martin as Maria and Theodore Bikel

as Captain von Trapp. The production cost

four hundred thousand dollars to stage,

a hefty budget back then. But the buzz was

electric. Ticket sales exploded, eventually

raking in over two hundred thirty-two million

dollars in advanced bookings alone. Let that sink

in—over two hundred thirty-two million dollars…

before most people had even seen the show.

Mary Martin barely took a day off—she only

missed one performance in the entire run. The

show ran for one thousand four hundred forty-three

performances, nearly four years, before closing

in June nineteen sixty-three. But by the summer of

nineteen sixty, something else started heating up.

A bidding war for the movie rights.

Studios knew this wasn’t just a hit—it

was a phenomenon. Twentieth

Century Fox came out on top, shelling out one million two hundred

fifty thousand dollars for the rights,

which would be more than thirteen million dollars

in today’s money. That was a shocking number,

especially for a studio in deep trouble.

Why? Because Cleopatra—Fox’s previous

big-budget epic—had nearly destroyed them. It

went fifteen million dollars over budget and

took down careers with it. Fox was bleeding

money. So when they bought the rights to The

Sound of Music, people thought they were crazy.

But the contract had one sneaky little clause: If

the film made more than twelve and a half million

dollars, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s estate would

get ten percent of the profits. Co-writer Howard

Lindsay literally laughed at it. He didn’t think

the movie would get anywhere near that number.

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

And now we get to one of the biggest

“what ifs” in Hollywood casting history…

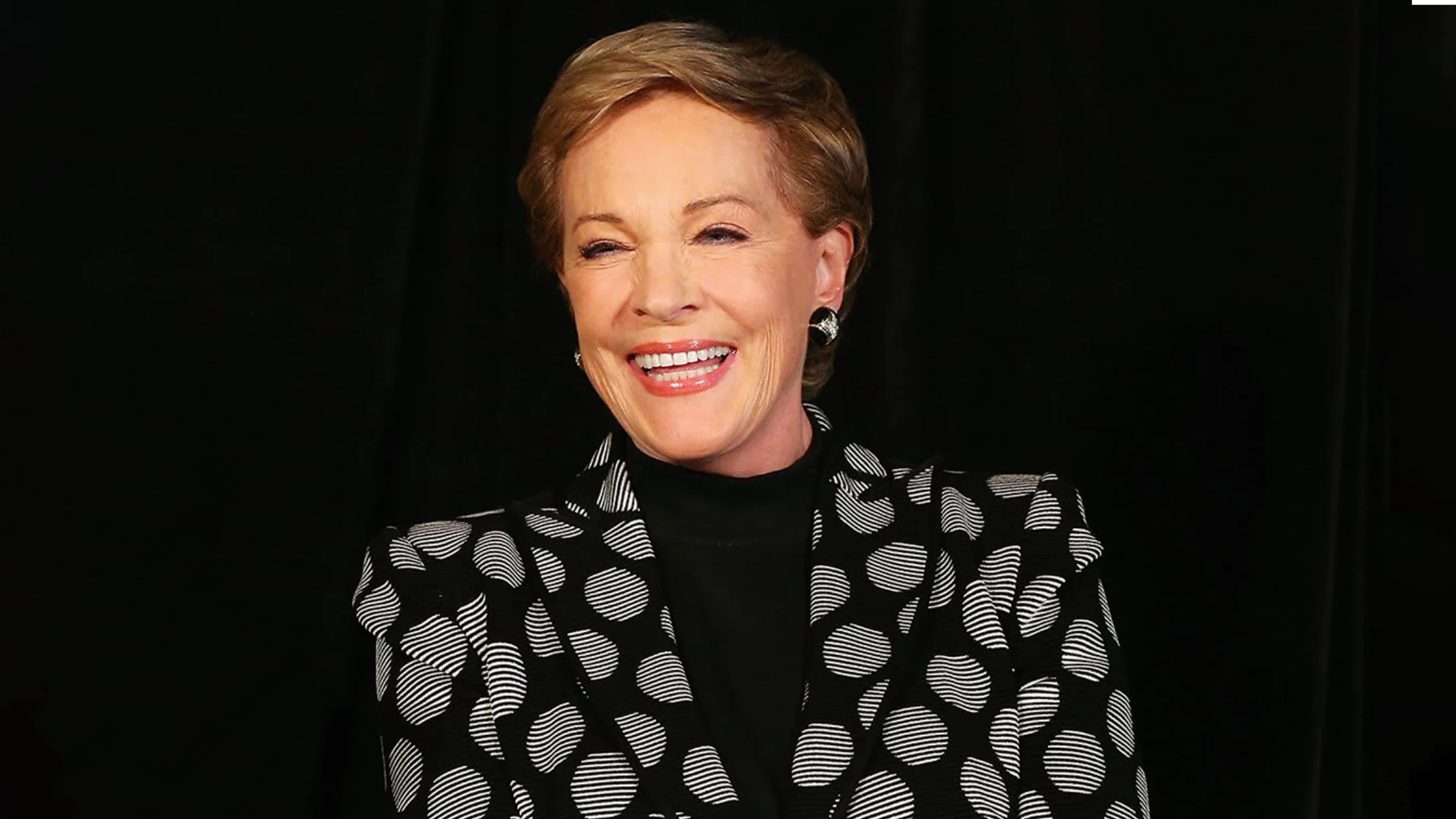

Julie Andrews’ Revenge: Hollywood’s Big Mistake

By the early nineteen sixties, Julie Andrews

had already conquered the stage. She was

beloved for her role as Eliza Doolittle

in My Fair Lady on Broadway. Her voice was

stunning, her charm undeniable. But when

it came time to turn My Fair Lady into a

film, Hollywood turned its back on her.

The studio heads said she wasn’t “camera-ready.”

In other words, they thought she wasn’t glamorous

enough for the big screen. So instead of

casting the woman who made the role famous,

they chose Audrey Hepburn—a move that

stunned Broadway fans. Audrey was elegant,

sure, but she couldn’t sing like Julie. In fact,

most of her songs in the film had to be dubbed.

Julie was devastated. She had

carried My Fair Lady for years, only to be passed over at the biggest moment. It

was the kind of snub that could’ve ended a career.

But fate had other plans.

Around that same time, director Robert Wise was looking for someone to play

Maria von Trapp in The Sound of Music. He wasn’t

convinced Julie was the right fit—until someone

at Disney showed him an early cut of Mary Poppins.

The film wasn’t even finished yet. But just a few

minutes in, Wise turned to the screenwriter and

said, “Let’s sign her—before anyone else does.”

Julie was offered the role of Maria for a flat

fee of two hundred twenty-five thousand dollars.

In today’s money, that’s about two point two eight

million dollars. It was a decent paycheck for

a rising star, but here’s the catch: there were

no royalties, no bonuses, and no box office

cut. Once she cashed that check, that was it.

Meanwhile, Mary Martin—who had played Maria

on stage—had negotiated a very different

deal. She earned more than eight million

dollars from her share of the Broadway

profits. Fox didn’t think Andrews was a

big enough star to deserve a back-end deal.

That decision would come back to haunt them.

Because Mary Poppins turned out to be a smash

hit. Julie Andrews not only proved the studio

wrong—she won an Oscar for Best Actress. And

when she accepted the award, she did something

cheeky. She thanked Jack Warner, the very man who

had rejected her for My Fair Lady. It was a sweet,

subtle form of revenge—and the audience loved it.

Still, The Sound of Music would become her

most iconic role. And even though the film

would go on to earn hundreds of millions

worldwide, Julie never saw a single dollar

beyond that original flat fee.

And she wasn’t the only one Fox tried to shortchange…

The Role No One Wanted

While Julie Andrews was already charming

everyone behind the scenes, casting her on-screen

partner was turning into a serious headache.

The role of Captain Georg von Trapp should’ve been

a dream gig—he was the handsome, brooding widower

who slowly falls in love with Maria. But here’s

the thing: no major actor wanted to play him.

Robert Wise, the director, tried everyone.

He considered Sean Connery, who had just

shaken the world as James Bond. He also

reached out to Richard Burton, known for

his intense performances—and his rocky

relationship with Elizabeth Taylor. Even Bing

Crosby was floated as a possibility. But none

of them fit the tone or spirit of the film.

Some said no. Others just didn’t seem right.

Then came Christopher Plummer. He

was classically trained, elegant, and sharp. But he didn’t like the script. At all.

In fact, Plummer thought The Sound of Music was

too sweet, too sentimental. He called it

“The Sound of Mucus” behind the scenes and turned down the role several times. The

idea of playing a strict, emotionally stiff

father in a musical didn’t interest him.

But Robert Wise believed in him. So he flew

to London to convince Plummer face-to-face.

Plummer agreed—but only under one condition:

he wanted to reshape the character.

He told the writers the captain needed more depth. More heart. Better dialogue. And most

of all, he needed his own song—something to show

his emotional side. That’s how Edelweiss ended

up in the film. It’s not an Austrian folk song,

like many believe. Rodgers and Hammerstein

actually wrote it for Plummer’s character.

The idea was to give the captain a

quiet, personal moment of vulnerability.

Even with those changes, Plummer still

struggled. He later admitted that he

drank through parts of the shoot. During the

filming of the family’s big farewell performance

to the Nazis—arguably one of the most intense

scenes—Plummer was actually drunk. He said it

helped him get through the stiffness of the role.

Despite all the tension, his performance worked.

He brought dignity and restraint to the captain,

making the character’s transformation—from

cold disciplinarian to loving father—feel

real. And audiences fell in love with it.

But here’s a wild twist: Christopher

Plummer also had a flat contract. No

royalties. No back-end deal. Just like Julie

Andrews, he walked away with a set paycheck.

As the film went on to gross over two hundred

eighty-six million dollars around the world,

both stars watched from the sidelines, cheered,

but did not receive beyond what was agreed on.

And while the adults were dealing with

contracts and rewrites, the younger cast

members were about to face their own chaos…

Liesl, Friedrich, and the Future Stars

The search for the von Trapp children was anything

but simple—and the competition was fierce.

Take the role of Liesl, the oldest

daughter. Believe it or not, a young Mia Farrow auditioned three times. She

was only twenty, still fresh-faced and delicate.

The casting team’s notes were blunt: “Sweet,

but no spark. Not enough energy. Can’t really

dance.” That was that. Farrow was out.

Ironically, the woman who did get the

part—Charmian Carr—was actually twenty-one.

Not years old. Twenty-one years older than

Farrow. Yep, Carr was cast to play sixteen

while already in her twenties. But she had

something Farrow didn’t: this confident glow

and graceful charm that lit up every room.

Losing out on The Sound of Music may have

stung for Farrow—but it opened the door to

something even bigger. Just a few years later,

she’d terrify the world in Rosemary’s Baby,

and her Hollywood path would never be the same.

As for Friedrich—the second-oldest child—one of

the actors who auditioned was Kurt Russell. Yes,

the same Kurt Russell who would later become an

action star. Patty Duke and Teri Garr also threw

their names in. But in the end, the role went to

Nicholas Hammond, a thoughtful, fifteen-year-old

kid with a calm intensity the director loved.

Years later, Hammond made history

in a whole new way—he became the very first live-action Spider-Man on

television in nineteen seventy-seven.

The rest of the von Trapp kids? They were

handpicked after grueling auditions. The

casting team searched for weeks, sometimes

months, until they found just the right faces,

voices, and personalities. And what they

built wasn’t just a cast—it was a family.

Even decades later, the actors who played the

children remained close. They reunited often,

supported each other through life events,

and kept in touch with both Julie Andrews

and Christopher Plummer until the very end.

Their bond felt real because it was real.

And the world noticed.

The Box Office Takeover

For nearly three decades, one film ruled

Hollywood’s box office like an untouchable king:

Gone with the Wind. Since its release in nineteen

thirty-nine, it sat at the top, undefeated through

wars, golden ages, and new technologies.

Then came The Sound of Music.

When it was released in nineteen sixty-five, no

one saw this coming. But by November of nineteen

sixty-six—just eighteen months later—it had done

the impossible. It dethroned Gone with the Wind,

raking in an unheard-of two hundred eighty-six

million dollars at the global box office.

And here’s the thing: that was not inflated

modern money. That was actual earnings,

based on ticket prices from the nineteen

sixties. Which makes it even more incredible.

To put it another way, The Sound of Music

sold two hundred eighty-three million tickets

around the world. That’s nearly one out

of every twelve people alive at the time.

People who didn’t even speak English were humming

Do-Re-Me. In villages without electricity,

folks still recognized Edelweiss.

And there was no viral marketing,

no online trailers, no streaming platforms. Just

word of mouth, radio mentions, glowing reviews,

and families going back to see it

a second, third, even tenth time.

It became more than a film. It became a global

phenomenon. A moment in history that people

shared, regardless of country, language, or age.

And then came the cherry on top—the Oscars.

The Sound of Music swept the Academy Awards,

winning five: Best Picture, Best Director,

Best Sound, Best Editing, and Best Score.

Director Robert Wise, who had already made

waves with West Side Story, proved

that lightning could strike twice.

This wasn’t just a fluffy musical anymore. Critics

had to admit it—it was art. Every technical

detail, every beat of editing, every soft piano

note, and crisp footstep was noticed and honored.

However, what people didn’t notice, what they

were never supposed to know, was the chaos

behind one of the film’s most romantic scenes.

The Gazebo Scene Disaster- The Forbidden Scene

The gazebo scene between Maria and

Captain von Trapp is one of the most beloved romantic moments in movie history.

You know the one—soft moonlight, quiet music,

a slow kiss as they finally confess their love.

But what you don’t know is this:

the scene was a complete disaster to film.

The problem? The lights. Specifically,

the massive carbon arc lights used to simulate

moonlight. These were industrial machines—bright,

hot, and loud. Really loud.

And not just any kind of loud. They made a noise that sounded exactly

like… a fart. A long, wet, flat raspberry.

Every single time Christopher Plummer leaned in to

kiss Julie Andrews—ppppfffftttttt. Over and over.

Julie said they tried twenty times. But the

moment they got close to each other’s faces,

the lights let out that same ridiculous sound.

They couldn’t stop laughing. Even the serious

lines—“Maria, I love you”—got destroyed

by giggles. The entire crew was helpless.

Hours went by. Nothing worked.

Eventually, director Robert Wise

gave up. He scrapped the original

plan. No more bright lighting.

Instead, he decided to shoot

the whole scene in silhouette. He placed Julie and Christopher in front of the

glowing gazebo windows. That way, their faces were

mostly hidden—and their laughter didn’t show.

It ended up looking even more romantic. That

glowing, dreamy style? That wasn’t

on purpose. It was damage control.

And the studio? They didn’t want anyone to

know. Twentieth Century Fox clamped down hard.

Cast and crew were warned not to mention the

noises, the laughter, or the failed takes.

For years, fans believed the scene

had gone off without a hitch.

The truth only came out decades later—when Julie

Andrews finally told the story on a talk show.

She laughed, remembering it: “It’s

very hard to be nose-to-nose doing a love scene and having these awful

raspberries coming at you from below.”

But while the audience laughed, no one

knew that Plummer himself was carrying a much heavier secret…

Plummer’s Private Misery

Christopher Plummer might have looked calm and

collected on screen, but behind the scenes,

he was deeply unhappy. He despised The Sound

of Music. He called it “gooey,” mocked it as

“The Sound of Mucus,” and even referred to it

in interviews as just “S&M.” To him, the movie

was overly sentimental—totally out of sync with

the serious, challenging roles he wanted to play.

And it showed. Plummer often isolated

himself during filming in Salzburg.

He once said the picturesque city felt

more like a “prison of sentimentality” than a European getaway. Part of that was his

own doing—he drank a lot and later admitted to

gaining weight from all the rich food and alcohol.

Still, he showed up. Always professional. Even

when he was drunk—which he openly confessed to

in later years. He said some scenes were filmed

while he was “three sheets to the wind,” including

one of the most emotional moments in the movie.

But somehow, in the middle of all

his resentment… Plummer gave a performance that would become iconic.

The Drunk Scene That Made Everyone Cry

There’s a moment in the film that gets

everyone emotional—when Captain von Trapp sings “Edelweiss” with tears in his eyes

during the festival. It feels so real,

so heartfelt… but here’s the twist: Christopher

Plummer was completely drunk when they filmed it.

He confessed in his two-thousand-eight memoir,

In Spite of Myself, that he had been drinking

heavily that day. He called himself a “young and

arrogant bastard” who had no real connection to

the film’s sentimental tone. And yet, he managed

to deliver a performance that moved millions.

And that’s the irony. The scene many fans

point to as proof of his character’s emotional

transformation… was carried by an actor who

could barely stand straight. Hollywood magic

at its finest—or its most bizarre.

But that wasn’t even the biggest

blow to his pride.

The Voice That Wasn’t His You know those scenes where Captain von

Trapp sings? Yeah… that’s not Plummer

singing. At least, not most of the time.

Turns out, the high notes and extended vocal

parts were performed by Bill Lee, a professional

singer who also did vocals for Disney movies like

Sleeping Beauty and Mary Poppins. Plummer’s

speaking voice was used for transitions and

dialogue, but when the real singing kicked

in—especially in “Edelweiss”—Lee took over.

Plummer was furious. He felt the decision

undermined his performance. But the producers

didn’t think he could pull off the vocal demands,

and they weren’t taking chances. Ironically,

most fans never noticed. Lee’s voice

blended so seamlessly that people still

believe they’re hearing Plummer sing.

By the time the movie came out, Plummer

was so annoyed he could barely say the film’s

name without an eye-roll. But decades later,

he admitted the film had “charmed” him in

the end. It just took a few decades—and

a lot of time away from the spotlight—for

him to see the impact it had on the world.

And while Plummer was quietly battling

his own demons, things on set were getting dangerously real for others too…

The Day Little Gretl Almost Died

Filming in Salzburg wasn’t just emotionally

draining—it was physically dangerous. During

the boat scene, where the von Trapp children

fall into the lake, five-year-old Kim Karath,

who played little Gretl, nearly drowned.

Here’s what really happened: just before

shooting, the crew informed Julie Andrews

that Kim couldn’t swim. So the plan was

for Andrews to fall toward the child when

the boat tipped and grab her immediately.

But when the boat flipped, everything went wrong.

Andrews fell backward—away from Gretl. Kim slipped

under the water twice before another actor jumped

in to pull her out. She ended up vomiting from

swallowing lake water and developed a

fear of swimming that lasted for years.

Even Julie Andrews was shaken. She later called

the incident one of the scariest moments on set.

But Gretl wasn’t the only one who took

a hit filming those now-iconic scenes.

The “Magical” Opening Scene That

Slammed Julie Andrews Into the Ground

We all remember it—Julie Andrews, arms

outstretched, twirling through a green alpine

meadow as the camera soars above her. It looks

peaceful, joyful, like something out of a dream.

But here’s what the audience didn’t see.

To get that sweeping aerial shot, a helicopter had

to fly just twenty feet above her. Each time it

circled around, the wind from the blades slammed

Andrews flat into the grass. She was knocked over

again and again, at least six or seven times,

and had to keep getting up, brushing off

dirt, and smiling like nothing happened.

She later joked in interviews that she was

almost launched into Austria. The scene

looked magical, but filming it felt

like a full-body tackle from the sky.

A Beautiful Disaster in Salzburg

Filming in Salzburg looked like a dream.

Rolling hills, perfect meadows, fairy-tale

castles—it was the ideal setting for a musical.

But behind the beauty was a nightmare.

The original budget for the film was

eight point two million dollars—already

expensive for the mid-nineteen sixties.

But no one warned the crew that Salzburg

had some of the worst weather in Europe.

Nineteen sixty-four turned out to be

one of the wettest years on record.

Director Robert Wise thought they could wrap

up location shooting in six weeks. It ended up

taking eleven. Rain delays brought everything

to a standstill. Over two hundred fifty cast

and crew members sat around in soggy clothes,

wasting time—and burning through the budget.

The cost of hotel rooms, equipment repairs, extra

meals, and rising wages made the studio executives

sweat. Fox was already reeling from the disaster

that was Cleopatra, and now this cheerful little

musical was threatening to blow up just as badly.

One studio insider even whispered:

“This movie might be the end of us.”

But there was one more unexpected shake-up

that made things even riskier…

The Director Who Walked Away

Long before Robert Wise was hired, the

legendary director William Wyler was

supposed to lead The Sound of Music. In

early nineteen sixty-three, he even quit

his spot on Fox’s board to avoid a conflict

of interest. That’s how serious it looked.

But Wyler had doubts from the start. He

didn’t like the stage musical. He didn’t

feel connected to the script. Even when he

flew to New York to see the Broadway show,

he left confused. The songs didn’t feel

natural to him—they just didn’t fit the story.

He said there was something else too. Wyler

was losing his hearing. It made directing

a musical even harder. His wife could

see it clearly: he just wasn’t into it.

So Wyler began quietly looking for a way

out. He needed a clean break—something that

wouldn’t raise suspicion. That’s when

producers offered him The Collector,

based on the John Fowles novel. Wyler read the

script and instantly knew this was more his style:

dark, twisted, psychological.

He asked the Zanuck family, who were running the studio, to release him

from his Sound of Music contract. The official

story? Scheduling conflicts. That’s what the

press was told. That’s what Fox repeated.

But the truth was, Wyler ran the other way. And

that left the door wide open for Robert Wise,

who stepped in late nineteen

sixty-three to pick up the pieces.

Thanks for watching, Fam! If you enjoyed

this video, be sure to like and subscribe

to our channel. Check out the next

video that pops up on your screen.

News

“You Think You Know… Then Everything Shatters” — Nicole Kidman’s Stark Truth About Life and Love’s Fragile Paths

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

Behind the Bangs and Bright Lights: Nicole Kidman’s Chilling Words on Life’s Unseen Detours Amid Split from Keith Urban

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

Nicole Kidman’s Haunting Words on Life’s Unraveling Amid Divorce—A Silent Storm Brewing Behind the Glamour!

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

From Chanel Runways to Broken Roads: Nicole Kidman’s Silent Battle and the Unexpected Strength Behind the Scenes

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

“You Think You Know, Then You Don’t”—Nicole Kidman’s Stark Revelation About Life Shattering Moments!

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

Behind the Bangs and the Smile: Nicole Kidman’s Cryptic Message on Life’s Twists Amid Divorce Drama!

As for country star Keith Urban and his ex Nicole Kidman, she’s breaking her silence about family amid their split….

End of content

No more pages to load