No one in the coastal settlement of Kisiwa remembered the day the soulless man was born—only the night. The elders would later argue about the date, but all agreed on the signs: the wind reversed itself without warning, the tide pulled back as if afraid of the shore, and every dog in the village howled until their throats bled dry. In the early years of the nineteenth century, such omens were not dismissed. They were cataloged. Feared. Whispered about long after the fires went cold.

The child came into the world just before dawn, beneath a roof of woven palm leaves and cracked clay tiles. His mother, Asha, did not scream. She did not cry out to God or ancestors. She simply stared at the ceiling as if something above it had already taken her attention. When the midwife lifted the boy, she froze. The infant breathed. His heart beat. His eyes opened. But the air around him felt wrong—thin, empty, as though something essential had been withheld.

Later, when the elders gathered and pressed their ears to the child’s chest, they declared what none of them fully understood: the boy had no soul.

In Kisiwa, the soul was not a metaphor. It was believed to be a weight, a heat, a presence that pressed outward from the chest. Even newborns carried it faintly, like embers under ash. This child carried nothing. No warmth. No pressure. No echo. He was alive in every way that could be measured, yet absent in ways that could only be felt.

They wanted to leave him in the forest before sunset.

It was Asha who stopped them. Weak from birth, her voice barely rose above the surf, but it cut through the council like a blade. “If God forgot something,” she said, “that is His mistake. Not my son’s.”

They named the boy Kofi. Not because the day demanded it, but because names were armor, and he would need one strong enough to survive suspicion.

Kofi grew.

That alone unsettled the village.

Children without souls were not supposed to live long. That was the old teaching. They withered, or wandered into rivers, or vanished during storms. But Kofi did none of that. He learned to walk. He learned to speak. He laughed—an odd, quiet laugh, as if he were imitating joy rather than feeling it, though no one could explain how they knew the difference.

By the age of seven, he worked the nets with the other boys. By twelve, he carried water for the elders without complaint. When sickness swept through Kisiwa one rainy season, it was Kofi who stayed with the fevered, wiping their brows, fetching herbs, sleeping on the dirt floors beside them while others fled in fear.

“Why does he do this?” the villagers whispered. “What does he gain, having no soul to save?”

Kofi never answered such questions. He listened. He learned. He loved in ways that confused even himself.

When Asha died, he sat beside her body until the ants came, holding her hand as if warmth could still travel between them. The priest watched from a distance, unsettled. Souls were supposed to grieve. Soulless things were not. Yet Kofi’s grief bent him nearly in half.

Years passed. Colonizers arrived with their flags and guns and ledgers, carving borders into land that had never asked for them. They brought churches and laws and a new language for God, one that insisted He was perfect, infallible, unchanging.

Kofi listened to that too.

He listened when the missionaries said God loved all souls equally. He listened when they said salvation was the destiny of the faithful. He listened when they spoke of hell for the damned. And each time, a question formed behind his eyes, unspoken, patient, dangerous.

What of those born without souls?

At twenty-six, Kofi fell in love.

Her name was Nia. She laughed too loudly, argued with spirits as if they were stubborn relatives, and once slapped a colonial officer without apologizing. She loved Kofi because he was steady. Because he did not judge. Because when she spoke, he listened as though every word mattered.

When she asked him if the rumors were true, he nodded. When she asked if he feared damnation, he shrugged.

“I fear hurting you,” he said. “I fear leaving things undone.”

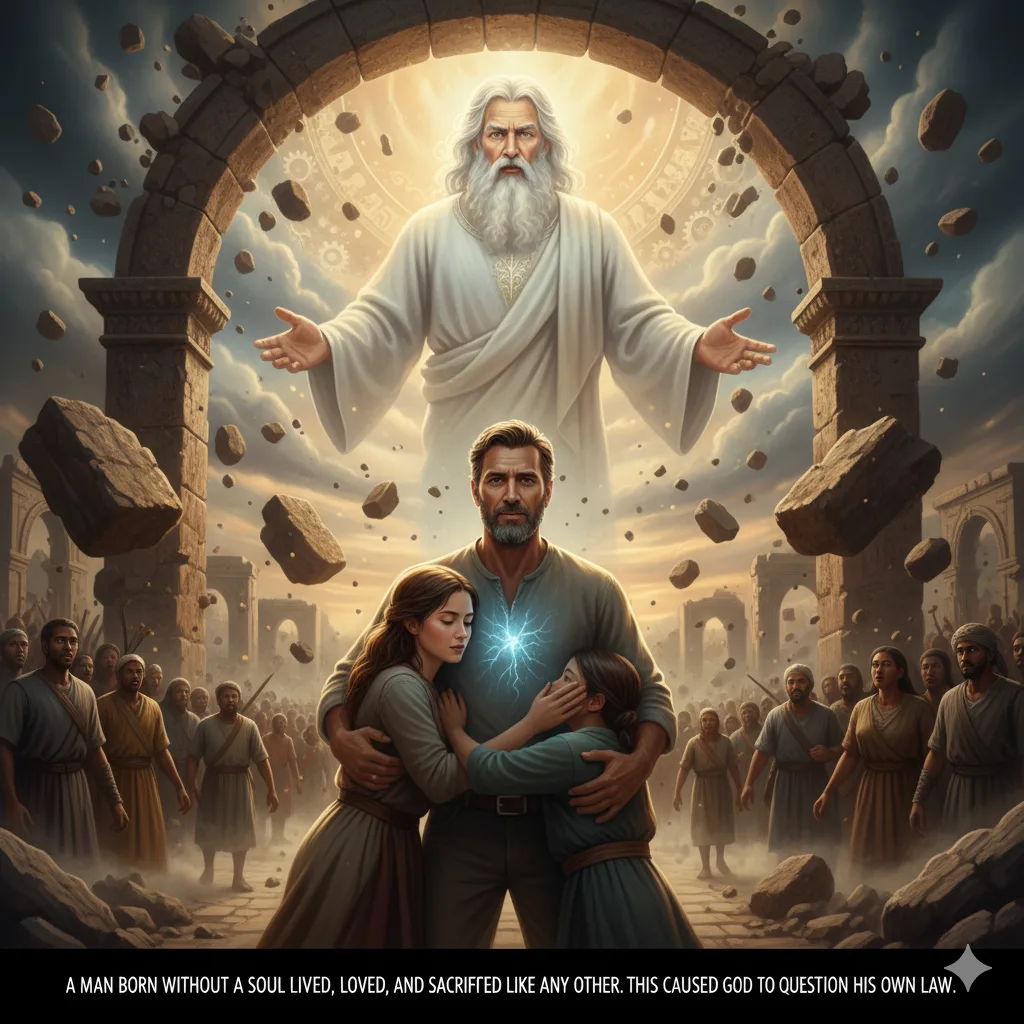

They married beneath a sky heavy with heat and expectation. The priest hesitated but performed the rite. After all, no law forbade a soulless man from loving.

When famine came, Kofi gave away his food. When soldiers came, he hid children beneath the floor. When punishment followed, he accepted it without bitterness.

It was this final act—this willingness to suffer for others without hope of reward—that sent a ripple beyond Kisiwa, beyond the coast, beyond time itself.

In the realm where laws were written before words, God paused.

He had not doubted Himself since the first light split the void. His rules were elegant. Souls were assigned. Lives followed. Justice resolved all things in the end. But now there was a man—alive, loving, sacrificing—who did not fit.

God looked upon Kofi and felt something unfamiliar.

Uncertainty.

For if a man without a soul could live a life of goodness greater than many who possessed one, what, then, was the soul for?

And if this was not an error…

What other laws might also be wrong?

Far below, in Kisiwa, Kofi knelt in the dirt, bleeding from a punishment meant to break him. He did not curse God. He did not pray.

He simply endured.

And somewhere beyond the stars, God began to watch more closely than ever before.

News

When the Cup Was Raised

No one in the river settlement of Kalema believed that time moved in straight lines. The elders said it folded…

The Beasts That Fear Built

The villagers first learned to fear the night long before they learned to name the things that moved within it….

When God Asked a Mother for Forgiveness

The disaster did not arrive with thunder.It came with silence. In the early months of 1803, along the red-earth coast…

THE SILENCE ON JUDGMENT DAY

At dawn, the sky over the colony did not break the way it always had. There was no gradual lifting…

The Blind Chronicler of God’s Silence

At the edge of the colony, where the red earth cracked like old scars and the wind carried the smell…

When God Knocked at Midnight

They called her cursed long before they called her by name. In the village of N’Kasa, pressed between a choking…

End of content

No more pages to load