At the edge of the colony, where the red earth cracked like old scars and the wind carried the smell of salt and rot from the distant coast, there lived an old blind man named Kafele. No one remembered when his eyes had gone dark. Some said he was born blind under a moonless sky. Others whispered that he had seen too much and that God Himself had taken his sight as mercy. In the early years of the nineteenth century, among the African villages pressed beneath colonial rule, blindness was not a weakness—it was a sign. The blind were believed to see what others could not.

Kafele lived alone in a hut made of mud and palm fiber, just beyond the missionary road. Every morning, before the bells of the foreign church rang, he sat cross-legged on the floor with a smooth wooden board on his lap. With his fingers, he traced carved symbols—lines and cuts passed down from elders long dead. He did not write with ink. He carved memory into wood.

The villagers called him the Listener.

They came to him at night, when fear grew louder than reason. Mothers whose children spoke in unfamiliar voices. Men who dreamed of fire raining from the sky. Women who woke with blood on their hands and no memory of how it got there. Kafele listened, nodding slowly, his clouded eyes staring into nothing. When they finished, he would say, “History is happening to you. Whether you like it or not.”

But no one knew the truth.

Kafele was not merely listening to people.

He was listening to God.

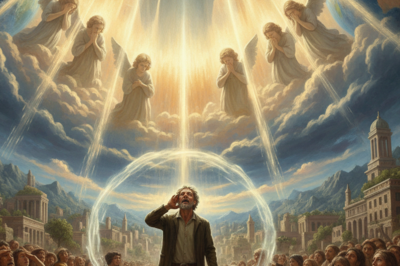

It began during the season of the long drought, when the river shrank into a ribbon of mud and bones. One night, as Kafele slept, the darkness behind his eyes grew heavier than usual. Then it opened. Not into light, but into depth. A voice spoke—not loud, not gentle, but absolute.

“Write.”

Kafele fell to his knees, trembling. “I am blind,” he said into the dark. “I cannot see the world.”

“You will not write what you see,” the voice replied. “You will write what is done.”

When he awoke, his hands were burning. The wooden board beside him was warm, as if freshly cut. Symbols he did not remember carving ran across it in perfect lines. Names. Dates. Events that had not yet happened.

From that night on, Kafele understood his calling. He was to be the recorder of mankind’s path—the witness of cruelty and mercy alike. He carved the arrival of foreign ships like white ghosts on the water. He carved the crack of whips and the fall of bodies in the cane fields. He carved treaties signed with smiling mouths and murderous hands. He carved prayers spoken in churches built over graves.

And each time, the voice returned.

“Write.”

The villagers noticed changes. Kafele aged faster. His back bent as if carrying an invisible load. Sometimes, while carving, he would stop suddenly, his hands shaking.

“Not this,” he would whisper.

“Write,” the voice insisted.

Fear spread quietly through the settlement. People began to avoid his hut at dusk. Children were warned not to touch his boards. “He knows what hasn’t happened yet,” they said. “He knows who will die.”

Then came the first omission.

It happened the night the soldiers came.

They arrived without warning, boots crushing the dry ground, torches slicing through the dark. They accused the village of hiding rebels. They demanded names. When no one spoke, they chose bodies instead. Men were dragged out. A young woman screamed as her husband was beaten until his bones sounded like breaking sticks.

Kafele heard everything.

The cries, the commands, the prayers that shattered mid-sentence.

The voice came to him, sharp and immediate. “Write.”

Kafele lifted his carving tool. His hands froze.

“What of the child?” he asked, his voice breaking. “What of the boy they threw into the fire?”

Silence.

Then, quieter than before: “Do not write that.”

Kafele’s breath caught in his chest. “Why?”

“That is not for history.”

The next morning, when the soldiers were gone and the village smelled of ash and blood, Kafele carved the event. He recorded the raid. The names of the dead men. The broken huts.

But there was no mention of the child.

The mothers noticed first.

“He didn’t write my son,” one woman whispered, staring at the board as if it might bleed. “Why is my son not there?”

Word spread. Kafele was summoned before the elders. They sat in a circle, faces carved with grief and suspicion.

“You write everything,” the chief said slowly. “Why not this?”

Kafele bowed his head. “I was told not to.”

“Told by whom?” another elder demanded.

Kafele did not answer.

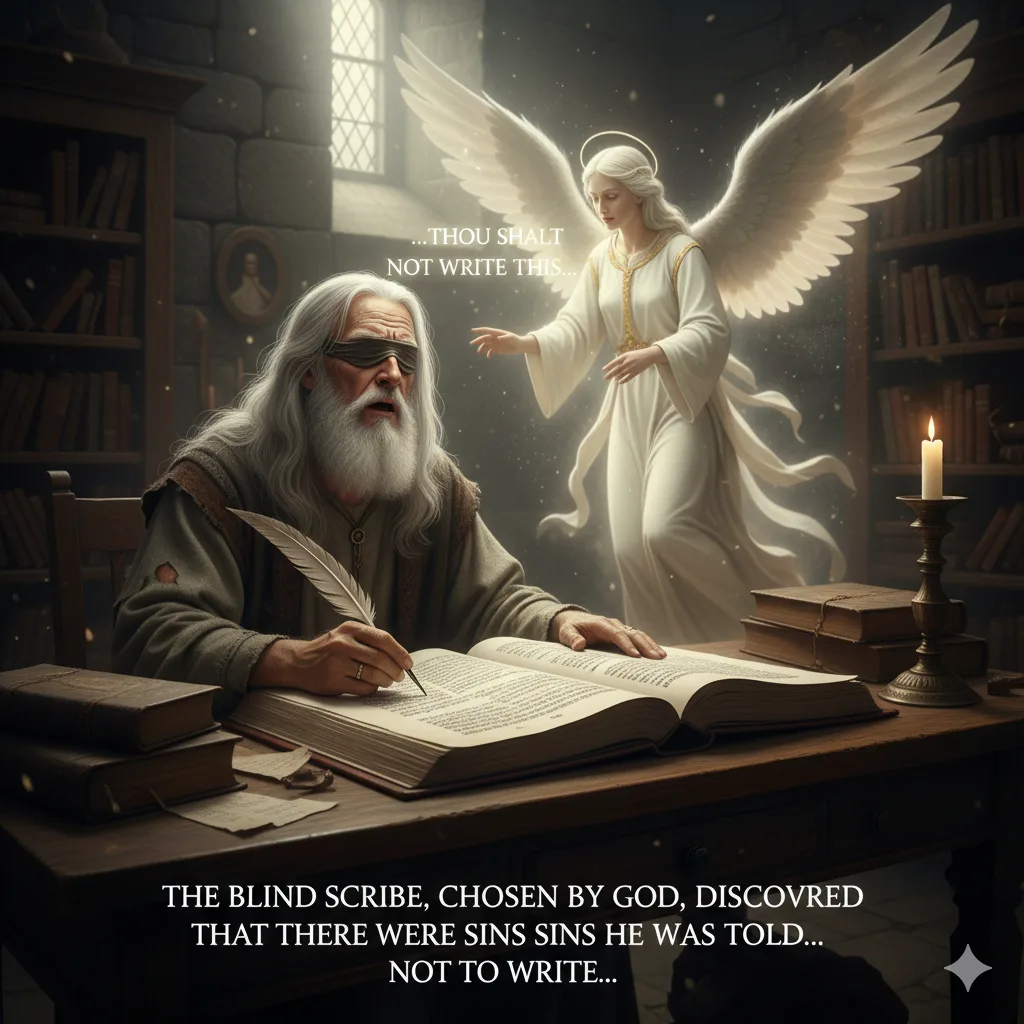

That night, the voice returned, heavier than ever.

“There are sins,” it said, “that must remain unrecorded.”

Kafele clenched his fists. “If history forgets them,” he said, “they will happen again.”

Silence stretched so long it felt like punishment.

Then the voice spoke, not as command, but as confession.

“Some crimes,” God said, “even I cannot look at directly.”

From that moment, fear turned into terror.

Kafele began to notice patterns. Certain atrocities were always excluded. Children. Betrayals committed in prayer. Acts done in God’s name but fueled by power. He carved around them, leaving gaps in the story—holes no one could explain.

The villagers sensed it. They whispered that God was hiding something. That heaven itself was ashamed.

Colonial officials soon heard rumors of the blind historian. A priest visited first, his accent thick, his smile rehearsed. He examined the boards, nodding approvingly.

“You are recording civilization,” the priest said. “Progress.”

Kafele turned his blind eyes toward him. “I am recording survival.”

The priest’s smile faded when he noticed the omissions.

“Where are the conversions?” he asked. “Where are the confessions?”

“Not all truths are meant to be carved,” Kafele replied, repeating words that tasted bitter in his mouth.

That night, soldiers returned—not to raid, but to collect. They took Kafele’s boards. They dragged him to the mission house. He was questioned for hours.

“You claim God speaks to you,” an officer scoffed. “Then ask Him why empires fall.”

Kafele said nothing.

In his silence, something shifted. The voice did not come that night. Nor the next.

For the first time, Kafele was alone.

Without the voice, memories flooded him—things he had been told not to write. Faces of children. Screams swallowed by hymns. Blood washed from church steps before sunrise.

His hands began to carve on their own.

When the soldiers returned days later, they found the walls of the cell covered in symbols. Not the careful lines of history—but frantic, overlapping marks.

“What is this?” one demanded.

Kafele smiled.

“This,” he said, “is what God didn’t want remembered.”

Outside, the villagers felt it before they heard it. A pressure in the air. A weight lifting and crushing at the same time. Dogs howled. Birds fled the trees.

And far away, beyond the colony, something ancient stirred—something that had been waiting for history to finally tell the truth.

Part One ended not with a written record, but with silence breaking open.

Because once the blind man began to write what even God feared to remember, the world itself would have to answer.

News

When the Cup Was Raised

No one in the river settlement of Kalema believed that time moved in straight lines. The elders said it folded…

The Beasts That Fear Built

The villagers first learned to fear the night long before they learned to name the things that moved within it….

When God Asked a Mother for Forgiveness

The disaster did not arrive with thunder.It came with silence. In the early months of 1803, along the red-earth coast…

The Man God Forgot to Finish

No one in the coastal settlement of Kisiwa remembered the day the soulless man was born—only the night. The elders…

THE SILENCE ON JUDGMENT DAY

At dawn, the sky over the colony did not break the way it always had. There was no gradual lifting…

When God Knocked at Midnight

They called her cursed long before they called her by name. In the village of N’Kasa, pressed between a choking…

End of content

No more pages to load