The villagers first learned to fear the night long before they learned to name the things that moved within it. In the early years of the nineteenth century, when the red dust of the African interior still swallowed foreign boots and the maps of Europe ended in guesswork, fear traveled faster than any caravan. It passed from mouth to mouth, from fire to fire, growing heavier each time it was spoken. Children learned it before they learned their prayers. Elders carried it in their silence. And somewhere between the drumbeats and the distant howl of animals, fear began to take shape.

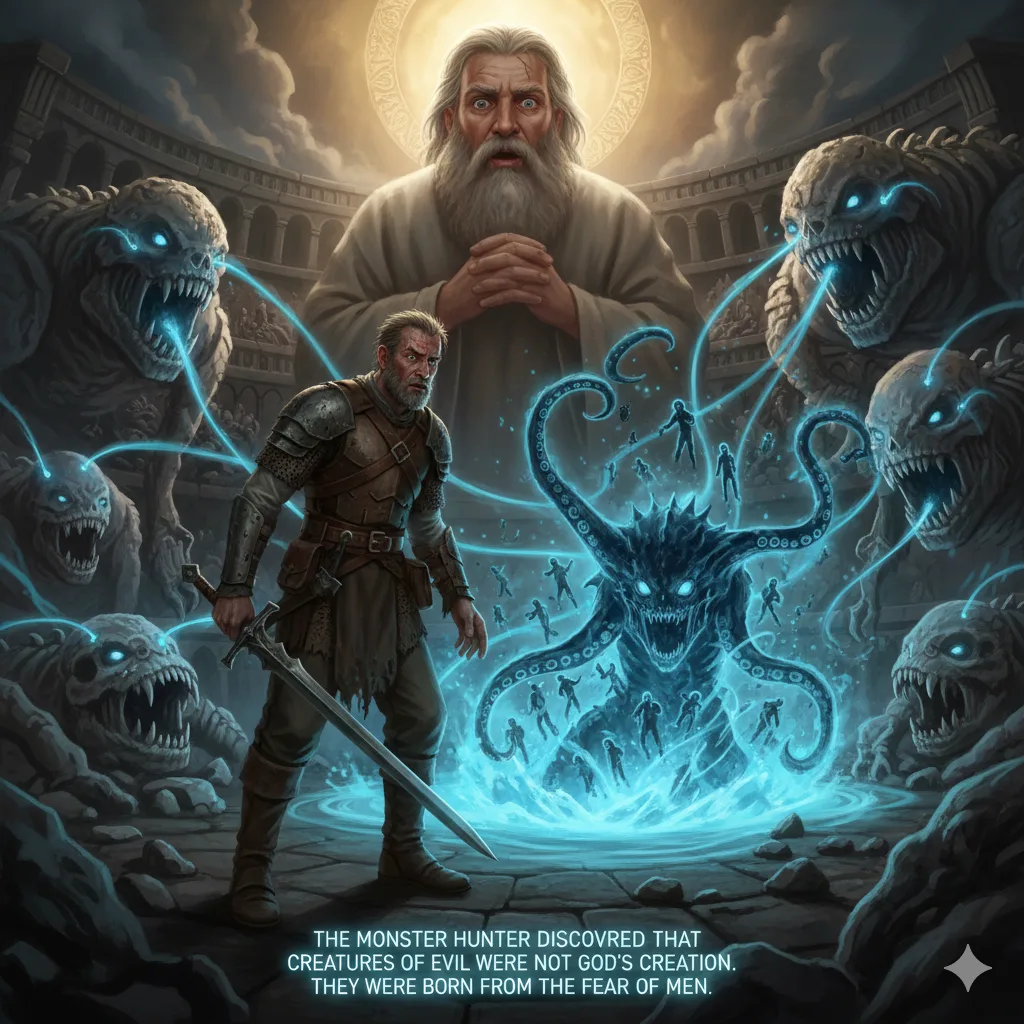

His name was Kofi, though few still used it aloud. To the people of the scattered settlements along the forest’s edge, he was simply called the hunter. Not of antelope, not of lion, but of things that should not exist. Monsters, they whispered. Demons. Cursed beings sent to punish a world that had forgotten its place beneath the sky.

Kofi had once believed that too.

He had been born in a village now erased from the earth, burned and abandoned after a single night of screams. He remembered the way his mother’s hands had trembled as she pushed a charm into his palm, how his father had taken up a spear knowing it would be useless. In the morning, there had been nothing left but footprints circling the ashes, too many, too close together, as if something with no true form had walked where people once lived.

That was the first beast he hunted, though he did not know it then.

Years later, Kofi walked alone. His rifle was old, traded from a Portuguese merchant who claimed it had once crossed the sea. Its barrel was scarred, its sound unreliable, but Kofi trusted it less than he trusted his own eyes. Around his neck hung not a cross nor an amulet, but a leather cord holding scraps of paper—names of villages, dates, symbols drawn by shaking hands. Records, he told himself. Proof that what he hunted was real.

The colonial outpost at Mbala had sent for him after the third disappearance. The administrator, a pale man sweating beneath a linen hat, spoke of savages and superstitions while his fingers drummed nervously on the desk.

“Something is killing them,” the man said. “Something unnatural. They say you’ve dealt with such things.”

Kofi said nothing. He had learned long ago that men who talked about monsters rarely wanted to hear the truth.

The villagers told a different story. Around the fire, they spoke of a creature with too many mouths, of shadows that peeled themselves off the trees, of a thing that wore the face of a grieving child. Each witness described something different, yet all agreed on one detail: the fear came first. Long before the attacks, people had felt watched. Long before blood stained the earth, rumors had taken root.

Kofi listened. He always listened.

That night, he followed the path beyond the village, past the fields abandoned in haste, into the forest where the air grew thick and the sounds of insects became a constant whisper. He did not pray. He did not call on God. He had tried that once, after his village burned. Heaven had remained silent.

The first sign was not a roar or a scream, but a smell—sharp, like sweat mixed with rot. Kofi slowed, heart steady, senses alert. He had learned that monsters announced themselves not with spectacle, but with absence. No birds. No wind. Even the insects seemed to hold their breath.

Then he saw it.

It stood between the trees, taller than any man, its outline wrong, as if drawn by a hand that had never seen a body before. Its limbs bent at angles that made Kofi’s eyes ache. Its face—or what might have been a face—shifted constantly, settling for a moment into something almost familiar before dissolving again.

This was the point where most hunters ran. This was where fear did its work.

Kofi raised his rifle, but did not fire.

He watched.

The creature did not attack. It swayed, uncertain, as if it were waiting for permission to exist. When Kofi took a step forward, it recoiled, its form blurring, thinning at the edges like smoke in sunlight.

He spoke, softly. Not a challenge. A question.

“What are you?”

The sound of his voice made the thing shudder. Its many mouths opened at once, but no words came out. Instead, images pressed into Kofi’s mind: the villagers whispering, mothers clutching children, men arguing by firelight about curses and punishment. Fear layered upon fear, night after night, until it had nowhere left to go.

The creature screamed then, not in rage, but in pain, and its body warped violently, growing sharper, more monstrous, as if trying to match the expectations placed upon it.

Kofi understood.

He lowered the rifle.

For the first time since he had taken up this cursed work, he did not feel hatred or triumph. He felt something colder and far more unsettling.

Recognition.

He had seen this before. In another village. Another forest. Another beast, slain after a night of terror. Each time, the stories had grown darker before the creature appeared. Each time, fear had preceded flesh.

“You were not made by God,” Kofi said, voice barely above a breath. “You were made by us.”

The creature collapsed inward, its form unraveling into wisps that sank into the soil like mist. No body remained. No trophy. Only silence, and the slow return of the forest’s sounds.

When Kofi returned to the village at dawn, the people were waiting. They searched his hands, his weapons, the ground behind him, looking for proof of victory.

“It’s gone,” he said.

They cheered. They wept. They thanked God.

Kofi turned away.

That night, as he packed his things, he wrote carefully on one of the scraps of paper hanging from his neck: Mbala region. Fear precedes form. No divine origin observed.

His hands shook as he tied it back into place.

Because if he was right—if these monsters were born not from hell, not from divine wrath, but from human terror—then killing them solved nothing. Fear would simply give birth to the next one.

And somewhere, in another village already whispering in the dark, something was beginning to take shape.

Part One ended not with a battle, but with a realization that was far more dangerous: the greatest monster Kofi hunted was not in the forest, but in the human mind—and it was spreading.

News

When the Cup Was Raised

No one in the river settlement of Kalema believed that time moved in straight lines. The elders said it folded…

When God Asked a Mother for Forgiveness

The disaster did not arrive with thunder.It came with silence. In the early months of 1803, along the red-earth coast…

The Man God Forgot to Finish

No one in the coastal settlement of Kisiwa remembered the day the soulless man was born—only the night. The elders…

THE SILENCE ON JUDGMENT DAY

At dawn, the sky over the colony did not break the way it always had. There was no gradual lifting…

The Blind Chronicler of God’s Silence

At the edge of the colony, where the red earth cracked like old scars and the wind carried the smell…

When God Knocked at Midnight

They called her cursed long before they called her by name. In the village of N’Kasa, pressed between a choking…

End of content

No more pages to load