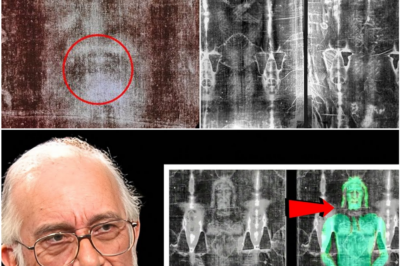

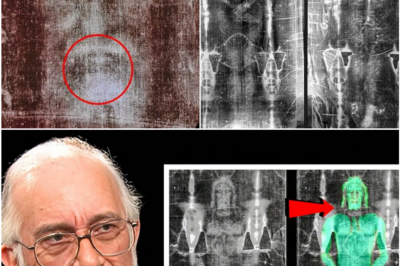

After decades of analysis, Barrie Schwortz’s renewed findings on the Shroud of Turin—driven by unexplained image properties and modern re-examination of old data—have reignited global debate, leaving scientists divided, believers shaken, and the world stunned by how much this ancient relic still refuses to explain.

In a revelation that is reigniting one of history’s most enduring religious and scientific debates, Barrie Schwortz, the American photographer and scientific documentarian best known for his work on the Shroud of Turin, has disclosed new findings that are leaving experts openly divided and deeply unsettled.

Speaking during a recent public lecture and follow-up interviews held in late 2025 in New York, Schwortz described evidence uncovered through renewed analysis of archival data from the original Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), the only comprehensive scientific examination ever authorized on the relic, conducted in Turin, Italy, in October 1978.

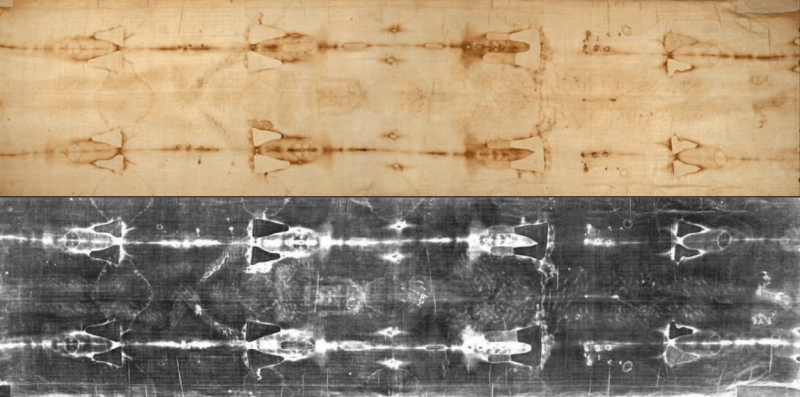

The Shroud of Turin, a 14-foot-long linen cloth bearing the faint image of a crucified man, has for centuries been venerated by millions as the burial shroud of Jesus Christ.

Officially housed in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, the relic has long sat at the crossroads of faith, skepticism, and science.

While carbon dating tests performed in 1988 suggested a medieval origin, critics have argued for decades that the samples used were contaminated or unrepresentative, leaving the mystery unresolved.

Schwortz, now in his late 70s, was the official documenting photographer for STURP and spent five full days and nights inside the cathedral photographing the Shroud using cutting-edge technology of the time.

According to him, what is now causing renewed shock is not a brand-new physical test, but a deeper re-examination of high-resolution images, spectral data, and microscopic observations that were recorded but never fully explained.

“There are characteristics in the image that we still cannot replicate or explain using known physical or chemical processes,” Schwortz said during his talk.

“And when you put all of them together, the problem becomes even bigger, not smaller.”

At the center of the controversy are image properties that appear to encode three-dimensional information, a feature first noticed in the 1970s but now analyzed with modern digital enhancement tools.

Researchers working independently with Schwortz found that the intensity of the image correlates precisely with the distance between the cloth and the body it covered, something unheard of in conventional art, photography, or staining.

Even more troubling to skeptics, chemical tests indicate that the image resides only on the topmost fibers of the linen, penetrating no deeper than a fraction of a micron.

“If this were paint, it would soak in.

If it were heat, it would damage the fibers.

If it were a scorch, we would see fluorescence patterns.

We see none of that,” Schwortz explained.

“What we see instead is a kind of surface-level oxidation that doesn’t behave like anything we can reproduce.”

The announcement has triggered immediate reactions across both scientific and religious communities.

Physicists and chemists have expressed cautious intrigue, while art historians and forensic experts are revisiting long-held assumptions.

On social media and academic forums, debate has erupted over whether the findings point to an unknown natural process, an advanced ancient technique, or something entirely outside current scientific understanding.

Notably, Schwortz stopped short of making theological claims.

“Science doesn’t deal in miracles,” he emphasized.

“Science deals in observations.

And right now, the observation is that this image is not behaving the way images are supposed to behave.”

Church officials in Turin responded with measured restraint, reiterating that the Shroud is an object of devotion, not dogma, while acknowledging that continued scientific inquiry is welcome.

Meanwhile, skeptics argue that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence and warn against drawing conclusions from legacy data.

Yet the emotional impact is undeniable.

For believers, the findings feel like vindication after decades of dismissal.

For skeptics, they represent an uncomfortable reminder that not all historical artifacts yield easily to explanation.

And for the public, the Shroud of Turin has once again become more than a relic—it is a question mark hanging between faith and reason.

As Schwortz concluded his remarks, he offered a final reflection that seemed to capture the moment: “After nearly fifty years, the Shroud hasn’t gotten simpler.

It’s gotten more complicated.

And that, to me, is the most honest result of all.”

News

Live on the Pulpit: Sarah Jakes’ On-Air Confrontation With Bishop Wooden Sparks a Reckoning Inside the Modern Church

During a live-streamed church service in Dallas, Sarah Jakes publicly confronted Bishop Harold Wooden over rigid traditions and generational divides,…

Shocking Revelation on the Shroud of Turin: Barrie Schwortz Uncovers Mystery That Has Scientists Baffled

After decades of investigation, Barrie Schwortz’s newly revealed anomalies on the Shroud of Turin have stunned scientists and reignited global…

Shocking Discovery on the Shroud of Turin Leaves Scientists Stunned – Barrie Schwortz Reveals What Could Change History

Barrie Schwortz’s shocking new analysis of the Shroud of Turin has revealed unexplained anomalies that challenge centuries of scientific and…

💥 Pope Leo XIV Announces 15 Radical Reforms That Could Reshape the Catholic Church Forever

Pope Leo XIV has unveiled 15 sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing the Catholic Church, addressing transparency, doctrine, and global operations,…

💥 Pope Leo XIV Unveils 15 Groundbreaking Reforms That Could Change the Church Forever

Pope Leo XIV has unveiled 15 unprecedented reforms at the Vatican that challenge centuries of Church tradition, sparking global shock,…

“‘Leo XIV’ Shockwaves the Vatican: Inside the Hypothetical Reforms That Could Redefine the Catholic Church”

Amid growing global pressure and internal crises, a hypothetical Pope Leo XIV is portrayed as unveiling 15 sweeping reforms to…

End of content

No more pages to load