Mel Gibson reveals how the mysterious Codex Gigas, the legendary Devil’s Bible with its terrifying illustration of Satan and unsolved medieval secrets, profoundly shaped his portrayal of evil in The Passion of the Christ, exposing the quiet, calculated nature of darkness and leaving both historians and audiences stunned by its chilling influence.

For centuries, the Codex Gigas—better known as the Devil’s Bible—has fascinated and terrified scholars, historians, and religious experts alike, and now Mel Gibson has admitted it profoundly influenced how he portrayed Satan in The Passion of the Christ.

Housed in the National Library of Sweden in Stockholm, this medieval manuscript is infamous for its enormous size, standing nearly three feet tall and weighing over 165 pounds, making it the largest known book from the Middle Ages.

Its creation around the early 13th century remains shrouded in mystery, with experts puzzled by the impossibly consistent handwriting of the scribe who completed it—an achievement that modern technology still cannot fully explain.

The Devil’s Bible is notorious not just for its size, but for its contents.

Alongside the complete Latin Vulgate Bible, the manuscript contains detailed histories, magical formulas, and an enigmatic full-page illustration of Satan himself, depicted in dark, terrifying detail.

For centuries, scholars debated its purpose and origin.

Some argued it was a monk’s attempt to atone for sins; others suggested darker forces guided its creation.

Mel Gibson, in a recent interview, described his first encounter with the manuscript as “deeply unsettling” and “transformative,” noting that its logic and precision in portraying evil without chaos resonated with him.

“It wasn’t about superstition,” Gibson said.

“It was about understanding how evil operates quietly, methodically, and often invisibly—and that changed the way I approached the Devil on screen.”

Gibson’s revelation comes after decades of secrecy surrounding the manuscript.

For years, he had privately studied photographs and reproductions of the Codex Gigas, drawn to the chilling illustration of Satan, which occupies an entire page of the book.

According to Gibson, the image of the devil, calm yet commanding, inspired the way he choreographed scenes of temptation, spiritual conflict, and moral decay in his 2004 film.

“There’s a quiet authority in that illustration,” Gibson explained, “and it’s terrifying precisely because it’s not chaotic.

It’s deliberate.

That’s what evil often is.”

Beyond its visual horror, the Codex Gigas has other mysteries.

Some pages were reportedly missing for centuries, including potentially forbidden texts that could shed light on occult practices, medical formulas, or even lost histories.

Handwriting analysis using modern AI and forensic technology has confirmed that nearly all the text was written by a single scribe, a feat that has baffled paleographers.

“The consistency is staggering,” noted Dr.

Henrik Svensson, a specialist in medieval manuscripts.

“We’re talking about decades of work by one individual, with no evidence of breaks or multiple contributors.

It’s almost impossible by today’s standards.”

The Devil’s Bible also contains other features that fascinate historians.

Marginal notes hint at local folklore, obscure prayers, and perhaps protective charms, suggesting that the book was not only a religious artifact but a cultural repository for its time.

Scholars have noted its influence on European literature, superstition, and early Christian art, but the codex’s allure lies in its unresolved mysteries.

From forbidden illustrations to cryptic Latin passages, the manuscript challenges the boundaries between fact and legend.

Gibson’s public acknowledgment has reignited interest in the manuscript.

The National Library of Sweden reports an increase in requests to study the Codex Gigas, while filmmakers and scholars alike examine its potential insights into the psychology of evil.

Film critics note that Gibson’s portrayal of Satan in The Passion of the Christ—calculated, subtle, and methodical—mirrors the manuscript’s depiction: a presence that is unnerving not through overt chaos, but through deliberate, quiet influence.

Interestingly, Gibson also pointed out that studying the Devil’s Bible changed his approach to storytelling in general.

“It’s not just about Satan,” he said.

“It’s about human choice, morality, and how even small, deliberate actions can create enormous consequences.

That’s the lesson the manuscript teaches, and it’s something I tried to bring into the film’s narrative.”

The Codex Gigas continues to inspire both fear and fascination.

Its unmatched size, unknown origins, missing texts, and haunting illustrations make it a timeless symbol of the enigmatic intersection of history, faith, and human curiosity.

For Mel Gibson, the manuscript became more than a historical curiosity—it became a blueprint for depicting the quiet, calculating force of evil, forever changing one of the most controversial films in Hollywood history.

With scholars, filmmakers, and the public still captivated, the Devil’s Bible stands as a chilling reminder that some truths from the past may never be fully explained—and some depictions of evil, once seen, cannot be unseen.

This revelation leaves the world wondering: what else in history hides lessons so powerful that they can shape modern storytelling, morality, and our understanding of darkness itself?

News

CALIFORNIA COAST IN FREEFALL: Giant Storm Waves Tear Cliffs Into the Sea as Scientists Sound the Alarm

A powerful winter storm has violently battered California’s coastline, with massive waves and torrential rain triggering rapid cliff collapses, flooding,…

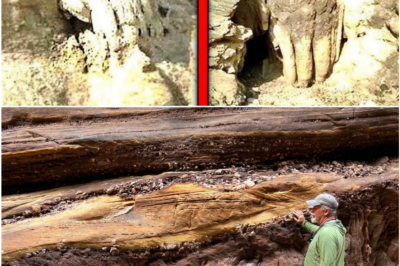

ALERT! The Grand Canyon Discovery Scientists Didn’t Want the Public to Panic Over

Scientists have uncovered vast hidden fractures and caverns beneath the Grand Canyon during routine surveys, a discovery caused by previously…

BREAKING: San Andreas Fault Shows New Cracks — NASA Warns of Rising Earthquake Risk

NASA warns that the San Andreas Fault is developing deep, previously undetected cracks, signaling rising earthquake risk in California, prompting…

OVERNIGHT SURGE SHOCKS CALIFORNIA: Lake Oroville Jumps 23 Feet as Storm Chaos Pushes Dam System to the Brink

Lake Oroville surged 23 feet in just three days after an unprecedented atmospheric river hit Northern California, overwhelming flood-control systems,…

Washington’s Hidden Crust Is Fracturing Beneath Our Feet — Scientists Confront a Geological Shift No One Expected

Deep beneath Washington State, scientists have discovered the Juan de Fuca Plate quietly cracking apart under immense pressure—an unexpected shift…

San Francisco Bay on Edge as King Tides and Powerful Storms Trigger a Rare Flood Chain Reaction

A rare collision of king tides and powerful storms has flooded parts of the San Francisco Bay Area, overwhelming aging…

End of content

No more pages to load