As decades of groundwater overdraft collide with delayed SGMA enforcement across California’s Central Valley, wells are failing, land is sinking, farmers are exiting, and rural families are left stunned and desperate as the reality of “nothing left” finally pours— or doesn’t— from the tap.

TULARE COUNTY, California — On a cold morning in late January 2026, Javier Morales twisted the handle of his kitchen faucet and waited.

Nothing came out.

Not a drip.

Not a hiss of air.

Just silence.

Outside his modest home near the town of Stratford, the well pump sat idle, its motor burned out after months of pulling from a water table that had sunk beyond reach.

“They told us to conserve,” Morales said, staring at the dry sink.

“We did.

Then one day there was just nothing left.”

Across California’s Central Valley, that moment is arriving for thousands of families and farmers—not because the state “forgot to rain,” but because decades of groundwater overdraft have collided with delayed enforcement, damaged infrastructure, and a reckoning long postponed.

In Tulare, Kings, Fresno, and Kern counties, wells are failing at accelerating rates, land is sinking inches at a time, and entire operations are shutting down as water math finally catches up with reality.

State records and local groundwater agencies confirm what residents already know: more water has been pumped out of the ground for years than nature can replace.

Almond orchards expanded.

Dairies multiplied.

During droughts, groundwater became the backup—and then the primary source.

“We treated groundwater like a credit card with no limit,” said a water district manager in Fresno County.

“Now the bill is due.”

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, known as SGMA, was passed in 2014 to stop exactly this outcome.

But enforcement was deliberately delayed to give local agencies time to plan.

That grace period is now over.

In late 2025 and early 2026, probationary actions, mandatory metering, pumping limits, reporting requirements, and new fees began hitting basins already on edge.

“SGMA didn’t cause the collapse,” said investigative journalist Megan Wright, who has been tracking groundwater filings and local enforcement actions.

“It revealed it.”

The impacts are uneven and deeply personal.

Domestic wells—shallower and less protected—are failing first.

In eastern Kings County, residents report hauling bottled water for months while nearby orchards remain green.

“The trees are deeper,” explained a well contractor who has been drilling nonstop since summer.

“Families lose water long before commercial farms feel it.”

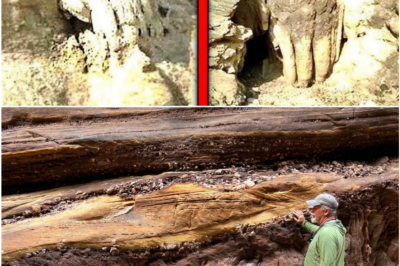

Land subsidence has made everything worse.

As aquifers empty, the ground sinks, cracking roads and damaging canals.

The Friant-Kern Canal, a critical artery delivering surface water to parts of the Valley, has lost capacity after sinking in multiple sections.

Repairs are slow and costly.

“You can’t move water through a broken channel,” said an engineer involved in assessments.

“And you can’t fix subsidence overnight.”

For farmers, the choices are stark.

Smaller operators without capital are selling land or letting fields go fallow.

Larger operations are consolidating water rights, drilling deeper wells, or paying rising fees to stay compliant.

“This is survival by balance sheet,” said a third-generation farmer in Tulare County who recently tore out 120 acres of pistachios.

“If you can’t afford the rules, you’re done.”

The economic ripple effects are spreading beyond agriculture.

Equipment suppliers, packing houses, and seasonal labor markets are shrinking.

Rural towns built around farming are watching tax bases erode.

“People think this is just about crops,” said a county supervisor in Kern County.

“It’s about schools, clinics, and whether these communities exist in ten years.”

State officials argue the pain is unavoidable and overdue.

Groundwater sustainability, they say, requires hard limits.

Critics counter that the delay in enforcement allowed overexpansion to continue, ensuring the eventual correction would be brutal.

“Sustainability arrived late,” Wright said.

“And when it arrives late, it arrives violently.”

For families like the Moraleses, policy debates feel distant.

What matters is water in the tap.

Javier’s wife, Elena, now drives twice a week to a distribution site with blue plastic barrels.

Their children ask when the water will come back.

“I don’t know what to tell them,” she said.

“You can’t explain aquifers to a six-year-old.”

As winter storms bring brief surface relief, groundwater levels remain dangerously low.

Experts warn that even wet years won’t reverse decades of depletion.

“This isn’t a drought story,” said the Fresno water manager.

“It’s a structural deficit.”

In the Central Valley, the phrase “nothing left” is no longer metaphor.

It’s a measured depth on a well log.

A dry faucet.

A sold farm.

And a region learning, painfully and in real time, what happens when sustainability comes after the water is already gone.

News

CALIFORNIA COAST IN FREEFALL: Giant Storm Waves Tear Cliffs Into the Sea as Scientists Sound the Alarm

A powerful winter storm has violently battered California’s coastline, with massive waves and torrential rain triggering rapid cliff collapses, flooding,…

ALERT! The Grand Canyon Discovery Scientists Didn’t Want the Public to Panic Over

Scientists have uncovered vast hidden fractures and caverns beneath the Grand Canyon during routine surveys, a discovery caused by previously…

BREAKING: San Andreas Fault Shows New Cracks — NASA Warns of Rising Earthquake Risk

NASA warns that the San Andreas Fault is developing deep, previously undetected cracks, signaling rising earthquake risk in California, prompting…

OVERNIGHT SURGE SHOCKS CALIFORNIA: Lake Oroville Jumps 23 Feet as Storm Chaos Pushes Dam System to the Brink

Lake Oroville surged 23 feet in just three days after an unprecedented atmospheric river hit Northern California, overwhelming flood-control systems,…

Washington’s Hidden Crust Is Fracturing Beneath Our Feet — Scientists Confront a Geological Shift No One Expected

Deep beneath Washington State, scientists have discovered the Juan de Fuca Plate quietly cracking apart under immense pressure—an unexpected shift…

San Francisco Bay on Edge as King Tides and Powerful Storms Trigger a Rare Flood Chain Reaction

A rare collision of king tides and powerful storms has flooded parts of the San Francisco Bay Area, overwhelming aging…

End of content

No more pages to load