A quiet, policy-driven breakdown in California’s trucking, warehousing, and agricultural systems is now forcing Costco to ration basic groceries statewide—thinning shelves not through panic or disaster, but through a slow, man-made collapse that feels controlled, unsettling, and far more dangerous because it’s happening in silence.

LOS ANGELES, California — Shoppers walking into Costco warehouses across California over the past two weeks have noticed something unsettling, not announced over loudspeakers and not posted in bold letters at the entrance, but printed quietly on small white placards taped near pallets and aisles: “Limit 2 per member.

” Rice.

Canned vegetables.

Bottled water.

In some locations, flour and cooking oil.

In others, bulk paper goods.

By January 18, 2026, at least 14 Costco warehouses from San Diego County to the Sacramento Valley had implemented purchase limits, according to employees and customers interviewed on-site.

Costco has not issued a public statement explaining the restrictions, but internal staff confirm the reason is simple and deeply troubling: the warehouses are not receiving enough inventory to keep shelves stocked.

“This isn’t panic buying,” said Luis Ramirez, a forklift operator at a Costco distribution hub in Riverside County.

“The trucks just aren’t coming like they used to.

Some days we’re unloading half of what we were getting last year.

” He pointed toward a row of empty dock doors, an image that would have been unthinkable during California’s peak supply years.

Unlike previous shortages triggered by COVID lockdowns, labor strikes at West Coast ports, or wildfires disrupting transportation corridors, this breakdown has no single dramatic cause.

Instead, it is the cumulative result of policy decisions unfolding over the past three years.

Investigative journalist Megan Wright, who has spent months tracking logistics data and interviewing supply chain managers, describes it as “a slow-motion collapse hiding in plain sight.”

At the center of the problem is trucking.

California’s aggressive emissions mandates, combined with enforcement of Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), have sharply reduced the number of independent owner-operators willing or able to operate within the state.

According to internal logistics estimates shared with Wright, California has lost tens of thousands of active long-haul and regional truckers since 2023.

“When you regulate the margins out of trucking,” Wright said during a recorded interview in Fresno on January 20, “food doesn’t stop being grown — it just stops moving.”

Warehousing is the second pressure point.

New zoning restrictions, energy-use caps, and compliance costs have made it increasingly expensive to operate large distribution centers.

Several regional cold-storage facilities in the Central Valley either downsized or closed entirely in late 2025, forcing retailers like Costco to rely on longer, less reliable delivery routes.

One warehouse manager in Stockton, speaking on condition of anonymity, said deliveries that once arrived daily are now spaced three to four days apart.

“If one truck gets delayed,” he said, “the shelves don’t recover.”

Agriculture, paradoxically, is both California’s strength and its vulnerability.

While the state remains the most productive agricultural region in the country, new water restrictions and fuel costs have reduced output consistency.

Almond growers, rice farmers, and vegetable producers have all reported delayed harvest transport.

“We can grow it,” said a third-generation rice farmer near Yuba City.

“But we can’t get it out fast enough, and when we do, it costs more than the buyer wants to pay.”

Inside Costco warehouses, the consequences are immediate and visible.

In Santa Clara, shopper Emily Chen noticed empty pallet spaces where 25-pound rice bags normally sit.

“There’s no chaos,” she said.

“That’s what scares me.

It feels controlled, like they don’t want us to notice.

” In Los Angeles County, another customer overheard employees discussing revised delivery schedules.

“One of them said, ‘We’re spacing it out so it doesn’t look bad,’” the shopper recalled.

Costco employees confirm that instruction.

“We’re told not to stack partial pallets too high,” said a night-shift stocker in Orange County.

“It makes the store look fuller than it really is.”

Economists warn that grocery rationing at warehouse retailers is often an early indicator, not a final stage.

“When bulk sellers start limiting staples, it means supply volatility has crossed a threshold,” said a former state logistics advisor now working in the private sector.

“Retailers are buying time.”

State officials have downplayed concerns, with one spokesperson describing the situation as “temporary distribution friction.

” But Wright disputes that characterization.

“This is structural,” she said.

“You can’t fix a broken supply chain with press releases.”

For now, California shoppers are adapting quietly, unaware that what looks like a minor inconvenience may be the first visible crack in the food system of America’s most productive state.

The signs are subtle, the shelves still mostly stocked — but the limits are real, the trucks are fewer, and the silence from officials is growing louder by the day.

News

CALIFORNIA COAST IN FREEFALL: Giant Storm Waves Tear Cliffs Into the Sea as Scientists Sound the Alarm

A powerful winter storm has violently battered California’s coastline, with massive waves and torrential rain triggering rapid cliff collapses, flooding,…

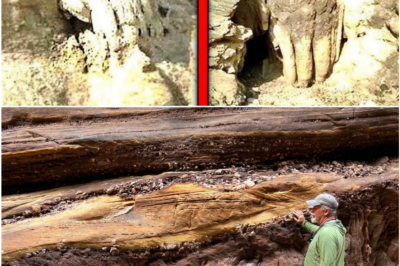

ALERT! The Grand Canyon Discovery Scientists Didn’t Want the Public to Panic Over

Scientists have uncovered vast hidden fractures and caverns beneath the Grand Canyon during routine surveys, a discovery caused by previously…

BREAKING: San Andreas Fault Shows New Cracks — NASA Warns of Rising Earthquake Risk

NASA warns that the San Andreas Fault is developing deep, previously undetected cracks, signaling rising earthquake risk in California, prompting…

OVERNIGHT SURGE SHOCKS CALIFORNIA: Lake Oroville Jumps 23 Feet as Storm Chaos Pushes Dam System to the Brink

Lake Oroville surged 23 feet in just three days after an unprecedented atmospheric river hit Northern California, overwhelming flood-control systems,…

Washington’s Hidden Crust Is Fracturing Beneath Our Feet — Scientists Confront a Geological Shift No One Expected

Deep beneath Washington State, scientists have discovered the Juan de Fuca Plate quietly cracking apart under immense pressure—an unexpected shift…

San Francisco Bay on Edge as King Tides and Powerful Storms Trigger a Rare Flood Chain Reaction

A rare collision of king tides and powerful storms has flooded parts of the San Francisco Bay Area, overwhelming aging…

End of content

No more pages to load