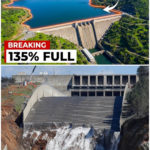

California’s Water Infrastructure on the Brink: Will Lake Oroville’s Flooding Lead to Catastrophe?

On January 27, 2026, Lake Oroville became the focus of an extraordinary climatic phenomenon that shattered the long-standing drought narrative Californians had come to accept.

Just two years prior, this vital reservoir was at a mere 27% capacity, with its boat ramps ending in dry dust and its waters receding alarmingly.

Fast forward to January 2026, and Lake Oroville has surged to an astonishing 135% of its historical average, showcasing a dramatic and unprecedented rise in water levels.

In a mere 24-hour period, the lake’s elevation increased by 0.64 feet, equivalent to 7.7 inches, resulting in the submergence of coastal properties, flooding of access roads, and the urgent evacuation of campgrounds that had seen little to no water in years.

As of now, the lake sits at 854.72 feet—just 46 feet below the emergency spillway that nearly failed during the catastrophic events of 2017, which led to the evacuation of 188,000 residents.

What makes this situation truly alarming is the nature of the storm systems responsible for this deluge.

Meteorologists from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center are tracking what they describe as unprecedented moisture convergence events.

These new weather patterns defy historical norms regarding frequency, intensity, and duration.

Dr. Michael Anderson, California’s state climatologist, highlighted in an emergency briefing on January 25 that we are no longer witnessing isolated storm events.

Instead, we are experiencing a continuous atmospheric moisture transport that far exceeds anything recorded in the past.

The pressing question now is whether California’s water infrastructure can cope with the unprecedented conditions that are unfolding.

Could this signify the dramatic end of California’s prolonged mega-drought?

Or does it reveal that the state’s water infrastructure—designed for 20th-century hydrology—is catastrophically unprepared for the extreme weather patterns of the 21st century?

To grasp the significance of Lake Oroville, one must understand its critical role within California’s water system.

Constructed in 1968, the Oroville Dam stands as the tallest dam in the United States, towering at 770 feet.

The reservoir behind it is capable of storing 3.5 million acre-feet of water, making it the second-largest reservoir in California, following Lake Shasta.

It serves not only as a regional water source but also as a lynchpin of the state water project, which transports water from Northern California to 27 million residents and 750,000 acres of farmland in the central and southern regions of the state.

The Feather River, which feeds into Lake Oroville, drains a massive 3,624 square miles of the northern Sierra Nevada.

During spring, when snow melts, this watershed can deliver flows exceeding 150,000 cubic feet per second—enough water to fill an Olympic swimming pool every two seconds.

For five decades, the system functioned as designed, with predictable seasonal patterns governing inflow rates, storage levels, and water temperature.

Winter storms would fill the reservoir, while spring snowmelt would maintain high water levels.

However, the prolonged drought that gripped California from 2012 to 2016 disrupted this predictability, leading to the driest period in at least 1,200 years.

By September 2015, Lake Oroville had plummeted to just 26% capacity, with boat ramps standing 100 feet above the waterline.

Marina facilities closed, and the hydroelectric plant, essential for powering 800,000 homes, was rendered inoperative for months as water levels fell below intake pipes.

Just as the state began to adapt to this new reality of permanent water scarcity, a series of atmospheric rivers struck in February 2017, overwhelming the drought-depleted reservoir.

Lake Oroville filled faster than operators could release water, leading to catastrophic erosion of the main concrete spillway.

Within hours, a massive hole formed, forcing the use of the emergency spillway for the first time in the dam’s history.

This led to the evacuation of 188,000 people downstream, as authorities feared a catastrophic failure that could unleash a 30-foot wall of water.

The repairs that followed cost $1.1 billion and took three years to complete.

Engineers rebuilt the main spillway with enhanced anchoring and erosion resistance, while the emergency spillway was fully reconstructed.

New monitoring systems were installed, and updated operational protocols were developed to prevent similar crises.

The message was clear: the infrastructure had failed catastrophically, but the repairs were intended to ensure that such an event would never happen again.

That confidence lasted until January 2026, when Dr. Sarah Chen, a hydrologist with the California Department of Water Resources, first detected anomalies in the data.

Her team monitors precipitation patterns across the Feather River watershed using an extensive network of rain gauges, snow sensors, and weather radar.

The data revealed that storm systems were deviating from typical atmospheric river patterns.

Normal atmospheric rivers, characterized by narrow corridors of concentrated moisture, usually last between 24 to 72 hours.

However, the January systems were not dissipating; they were regenerating.

Meteorological analysis indicated a persistent pattern of low-pressure systems forming over the western Pacific, drawing moisture from tropical latitudes and establishing semi-stationary positions off the California coast.

Each system pumped moisture inland for days, weakening only to be reinforced by the arrival of the next system before the first had fully dissipated.

This resulted in continuous precipitation across the watershed, rather than discrete storm events, creating a situation akin to a fire hose delivering water.

By January 15, 2026, the Feather River Basin had received an astonishing 24 inches of precipitation—more than the average winter’s total accumulation—within just two weeks.

Snowpack at elevations from 6,000 to 8,000 feet measured 287% of normal, but critically, the snow line was unusually high above 7,000 feet.

This meant that much of the precipitation fell as rain directly into the reservoir instead of being stored as snowpack for gradual spring release.

Inflows to Lake Oroville skyrocketed from 15,000 cubic feet per second on January 10 to 87,000 cubic feet per second by January 20.

By this point, the reservoir, which had started January at 67% capacity, began rising at rates exceeding 2 feet per day.

Dr. Chen recognized the impending problem.

The revised operational protocols required maintaining storage space for flood control, keeping the reservoir below 850 feet until the wettest period of winter had passed.

This flood space was designed to capture sudden inflows without necessitating emergency releases.

However, these protocols were based on the assumption of discrete storm events with recovery periods in between, which did not account for the continuous multi-week moisture delivery that was occurring.

On January 22, Lake Oroville reached 850 feet, triggering the requirement for increased spillway releases.

Dam operators opened the main spillway to 50,000 cubic feet per second, attempting to release water as quickly as safely possible given the downstream flood risks.

Despite their efforts, the reservoir continued to rise, with inflows exceeding outflows by 30,000 to 40,000 cubic feet per second.

Each day added another 1 to 2 feet of elevation.

As Dr. Chen contacted the National Weather Service California Nevada River Forecast Center, the forecast showed no relief in sight.

Another major atmospheric river was predicted to arrive on January 28, potentially delivering an additional 8 to 12 inches of precipitation across the watershed.

On January 24, the California Department of Water Resources convened an emergency operations meeting.

Twenty-three engineers, hydrologists, and emergency management officials reviewed various scenarios.

Their analysis revealed a crisis unfolding in slow motion.

If current inflow rates continued and the forecast storm delivered the predicted moisture, Lake Oroville would reach the emergency spillway elevation of 900 feet within 10 to 14 days.

Using the emergency spillway is not necessarily catastrophic; it was rebuilt specifically to handle such conditions.

However, the structure has never been tested under actual operational conditions since its reconstruction.

While computer models and physical testing suggest it would perform as designed, models are not reality.

More concerning, if inflows continued at extreme rates after the emergency spillway activated, the reservoir could approach maximum capacity, leading to uncontrolled releases that could cause structural damage and downstream flooding far exceeding anything California’s emergency response systems are prepared to handle.

The meeting concluded with a recommendation to begin coordinated releases from all state water project and Central Valley project reservoirs to create downstream capacity for increased flows.

They also advised notifying downstream communities of elevated flood risks and preparing evacuation plans for the 200,000 residents living in potential inundation zones.

This recommendation was classified as preliminary operational guidance and was not released to the public.

Three days later, someone leaked this information to the Sacramento Bee, revealing California’s impossible position.

Lake Oroville feeds the Feather River, which converges with the Sacramento River near Verona.

The Sacramento River, already swollen from its own watershed’s precipitation, flows through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta—the hub of California’s water infrastructure.

Here, fresh water from northern rivers meets saltwater intrusion from San Francisco Bay.

The Delta supplies water to 27 million Californians through a complex network of pumps, channels, and aqueducts.

However, it is also a fragile ecosystem supporting endangered fish species and hundreds of square miles of farmland built on peat soils below sea level, protected by levees constructed over the past century.

Increasing releases from Oroville means higher flows through the Sacramento River and into the Delta.

This puts stress on the aging levees, and if they fail, saltwater intrusion accelerates.

Agricultural lands could flood, and water export pumps may need to shut down to prevent salinity contamination.

It is a zero-sum equation: release too much from Oroville, and you threaten Delta infrastructure; release too little, and the reservoir approaches dangerous levels.

By January 26, with Lake Oroville at 854.72 feet and still rising, dam operators faced a brutal choice.

They increased spillway releases to 100,000 cubic feet per second—the maximum rate deemed safe for downstream conditions, given current Delta levee assessments.

Despite these efforts, the reservoir continued to rise, and communities downstream began preparations.

Marysville, a city of 12,000 people protected by levees designed for 100-year flood events, activated emergency operations centers.

Evacuation routes were checked, emergency shelters were established, and police conducted door-to-door notifications in vulnerable neighborhoods.

However, preparation requires time that might not exist.

On January 27, the National Weather Service issued an update predicting 10 to 15 inches of precipitation across the Feather River watershed between January 28 and February 2.

With soil already saturated and snowpack primed for rain-on-snow melt events, runoff efficiency would approach 90%, meaning nearly all precipitation would flow directly into streams feeding the reservoir.

Projected inflows were expected to reach 120,000 to 150,000 cubic feet per second, sustained over 5 to 7 days.

Even with maximum spillway releases, Lake Oroville could gain 15 to 20 feet, pushing its level to between 870 and 875 feet—within 30 feet of the emergency spillway.

Forecast models indicated another system developing behind this one, potentially arriving on February 6 to 8.

Dr. Chen ran the scenarios repeatedly, hoping for different results, but each simulation yielded the same outcome.

Without a multi-week break in precipitation or a significant increase in release capacity, the reservoir would reach the emergency spillway by mid-February.

The Governor’s Office of Emergency Services began quiet preparations for the potential evacuation of 200,000 people from Butte and Sutter counties—the same population that had evacuated in 2017.

California’s response plan, developed after the 2017 crisis, was comprehensive and sophisticated.

It emphasized increased coordination between reservoir operators, real-time monitoring networks, pre-positioned emergency equipment, public notification systems, and evacuation protocols.

On paper, the state was prepared for another Oroville crisis.

However, implementation revealed the gap between plans and reality.

Increasing releases from Oroville required coordination with operators of Shasta Dam, Folsom Dam, and New Melones Dam, the other major reservoirs in the Central Valley system.

All were above normal levels due to the same storm pattern, meaning that creating downstream capacity required simultaneous increases in releases while ensuring the Sacramento River did not exceed flood stage.

Coordination was essential, and it initially worked.

By January 27, releases from the four major dams were synchronized to maintain Sacramento River flows just below flood stage at key measurement points.

But then Folsom Dam reported a problem.

High flows were causing erosion at the base of the auxiliary spillway—different from the main spillway but still handling significant flows.

Inspection teams found evidence of concrete deterioration that had not been visible during routine maintenance.

Continuing high releases risked propagating this damage.

Folsom operators reduced releases by 30%, shifting the burden back to other facilities.

Oroville had to absorb the difference, limiting its release capacity.

Downstream levee concerns added another layer of complexity.

The Delta Stewardship Council identified 23 levee sections showing signs of instability due to prolonged high water levels.

These levees protected islands housing 4,000 residents and critical water infrastructure.

Continued high flows increased the risk of failure.

The reclamation district boards responsible for levee maintenance requested flow reductions to allow for emergency repairs.

The California Department of Water Resources faced contradictory demands: release more water from Oroville to protect the dam, or release less to protect downstream levees and infrastructure.

Environmental regulations further complicated matters.

The Federal Endangered Species Act mandates maintaining specific flow conditions and water temperatures to protect delta smelt, winter-run Chinook salmon, and other threatened species.

Cold water releases from Oroville helped maintain these conditions, but only within specified operational ranges.

Maximizing spillway releases would mean warmer water temperatures in downstream reaches, potentially violating take permits and triggering federal regulatory action that could force operational changes mid-crisis.

Every solution created new constraints, revealing infrastructure limitations that the planning process had assumed would not bind simultaneously.

By January 28, as the forecast storm began delivering moisture, Lake Oroville was rising at 0.8 feet per day despite maximum operationally feasible releases.

The reservoir stood at 856 feet—45 feet below the emergency spillway—but with 10 to 14 days of projected inflows, it was set to gain 15 to 20 feet of elevation.

The math was straightforward and brutal: barring a dramatic change in weather patterns, the emergency spillway would activate in early February.

Public communication became its own crisis.

After the leak to the Sacramento Bee, news coverage exploded, with cable networks sending crews to Oroville.

Social media buzzed with speculation, comparisons to 2017, and demands for immediate mass evacuation.

The California Department of Water Resources held daily press briefings, emphasizing that while conditions were serious, they were not analogous to 2017.

The infrastructure had been rebuilt, and the emergency spillway was designed for this exact purpose.

Evacuation was not currently warranted but might become necessary if conditions worsened.

The messaging attempted to strike a careful balance: acknowledge risk without inciting panic, maintain public trust while preparing for potential evacuation, and demonstrate competence while admitting uncertainty.

However, it satisfied almost no one.

Downstream residents demanded guarantees that could not be provided.

Politicians sought explanations for why fixed infrastructure was facing renewed crisis.

Activists pointed to climate change as the root cause, arguing that infrastructure repairs had not addressed the underlying issues.

Dr. Chen, thrust into a public-facing role as the state’s technical expert, tried to convey the complexity of the situation.

He stated, “We are managing a system designed for climate patterns that no longer exist. 20th-century infrastructure confronting 21st-century hydrology. The dam is safe. The repairs are sound. But we are operating in conditions outside the design parameters.”

Unfortunately, this nuance was lost amidst the 24-hour news cycle demanding simple answers.

Is there a crisis or not?

Should people evacuate or not?

Is the dam failing or not?

The honest answer—managing elevated risk in real time, with more clarity expected as conditions develop—translated poorly into headlines.

By January 30, three days into the forecast storm event, precipitation exceeded predictions.

The Feather River watershed recorded 13 inches in just 72 hours—the highest three-day total since records began in 1893.

Inflows to Lake Oroville peaked at 134,000 cubic feet per second.

The reservoir gained 2.1 feet in 24 hours, reaching 858.8 feet.

Dam operators were releasing 105,000 cubic feet per second, pushing the absolute limits given downstream conditions.

Water continued to accumulate at a net rate of 29,000 cubic feet per second.

At this rate, the emergency spillway would activate in 11 days.

The storm persisted through January 31 and into February 1, but unexpectedly weakened.

By February 2, precipitation had ceased, and inflows began to decline.

Lake Oroville peaked at 862.3 feet on February 3, remaining 39 feet below the emergency spillway, and began to recede slowly as releases exceeded inflows.

The immediate crisis passed, but the next forecast atmospheric river was still projected for February 6 to 8.

Today, Lake Oroville remains at historically high levels, with dam operators maintaining elevated releases.

Downstream communities remain on alert as meteorologists track the next system developing over the Pacific.

The emergency spillway has not been used, and evacuations have not been ordered.

The infrastructure performed as designed, but the margin of safety—the buffer between normal operations and emergency conditions—has collapsed to days rather than weeks or months.

The question now is no longer whether California’s water infrastructure can handle normal variability.

Instead, it is whether infrastructure designed for 20th-century climate can manage 21st-century extremes that are quickly becoming the new normal.

From 2012 to 2016, California adapted to permanent drought, investing in desalination, groundwater banking, water conservation, and drought-resistant agriculture.

Billions of dollars and countless policy changes were predicated on the assumption that water scarcity was the fundamental challenge.

Now, in 2026, the state faces the opposite crisis: an overwhelming influx of water arriving too quickly for infrastructure to manage safely.

Reservoirs designed for seasonal storage are being overwhelmed by continuous inflows, while spillways built for occasional use are operating near maximum capacity for extended periods.

Levees designed for periodic high water phases are under sustained stress.

California is coming to realize that climate change does not equate to a linear transition from one stable state to another.

Rather, it signifies volatility, with extreme drought transitioning to extreme flood, leaving infrastructure unable to adapt swiftly enough to either condition.

Lake Oroville’s current status at 135% of its historical average does not indicate that the drought is over.

Instead, it serves as evidence that historical averages are becoming increasingly meaningless.

The hydrology that shaped California’s water system for 150 years—characterized by wet winters, dry summers, predictable snowmelt timing, and manageable variability—is being replaced by unprecedented patterns.

Atmospheric rivers that regenerate continuously, precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, and storm systems arriving in rapid succession are reshaping California’s water landscape.

Engineers can design for known variability, but they cannot anticipate variability whose range is expanding more rapidly than infrastructure can be upgraded.

As Dr. Anderson, the state climatologist, stated in a February 4 briefing, “We are operating infrastructure designed for climate conditions that existed from 1900 to 2000. We are experiencing climate conditions that have no analog in that period.”

Every dam, every levee, and every reservoir in California was constructed for a climate that no longer exists.

The systems we built to manage water—the dams that store it, the spillways that release it, the levees that contain it, and the aqueducts that transport it—have collectively created an infrastructure lock-in.

We cannot easily replace or upgrade systems that took decades to build and cost billions of dollars.

This lock-in constrains options, forcing us to operate 20th-century infrastructure in a 21st-century climate.

As extreme events continue to push systems toward their limits, we are left wondering which component will fail first.

Are we truly managing California’s water, or merely delaying the inevitable recognition that our infrastructure cannot handle the extremes we have created through climate modification?

As we navigate this precarious situation, the instruments continue to transmit data, Lake Oroville rises and falls with each storm, dam operators release water according to protocols, emergency managers update evacuation plans, and meteorologists track the next atmospheric river.

The system keeps responding moment by moment, while moisture drawn from tropical latitudes continues to organize into the next weather system that will put to the test the infrastructure built for a climate that no longer exists.

Communities will face impossible choices as millions of people wonder if the structures designed to protect them will hold.

The Pacific Ocean carries the next test, and Lake Oroville is not overflowing because we failed to build strong enough dams.

It is nearing capacity because we constructed infrastructure for predictable variability and created a climate that delivers unprecedented extremes.

Who will bear the cost when the next atmospheric river arrives?

When reservoir space runs out, when downstream levees fail, when the emergency spillway activates, we will discover whether the repairs actually work under real-world conditions that exceed every test scenario.

That question remains unanswered, leaving only the sound of water rising, the calculations showing diminishing safety margins, and the uncomfortable acknowledgment that we have built a system where success and failure are separated by mere days rather than the months or years our ancestors believed would always provide sufficient warning.

News

😱 NO MORE CHANCE! HARRY APOLOGIZES To CHARLES In Tears. ANNE EXPOSES HARRY’S DECEPTION On GENEVA. 😱 – HTT

😱 NO MORE CHANCE! HARRY APOLOGIZES To CHARLES In Tears. ANNE EXPOSES HARRY’S DECEPTION On GENEVA. 😱 In a rare…

😱 Jesus to Return! Shocking Archaeological Discoveries That Prove the Bible Is True 😱 – HTT

Jesus to Return! Shocking Archaeological Discoveries That Prove the Bible Is True The sea keeps its secrets, but what if…

😱 Sandra Bullock Defended By Quinton Aaron Amid Calls to Return ‘Blind Side’ Oscar 😱 – HTT

😱 Sandra Bullock Defended By Quinton Aaron Amid Calls to Return ‘Blind Side’ Oscar 😱 The controversy surrounding the hit…

😱 BREAKING NEWS: California Coast Breaking Apart! Huge Waves Make Science Issue RED ALERT! 😱 – HTT

😱 BREAKING NEWS: California Coast Breaking Apart! Huge Waves Make Science Issue RED ALERT! 😱 California’s coastline is facing a…

😱 Celestial Signs Over Jerusalem: The Shocking Appearance of Jesus and an Army of Angels! 😱 – HTT

3 Minutes Ago! Jesus and Army of Angels Appears In JERUSALEM! He is Coming! Last night, something truly unbelievable lit…

😱 Quinton Aaron Defends Sandra Bullock: The Shocking Truth Behind Michael Oher’s Lawsuit Against the Tuohy Family! 😱 – HTT

Quinton Aaron Stands Up for Sandra Bullock Amid Michael Oher’s Legal Battle with the Tuohy Family In the wake of…

End of content

No more pages to load