EMERGENCY: San Francisco Fault System Just Woke Up After 160 Years!

One minute ago, the ground beneath San Ramon shuddered for the 300th time this month.

Dishes rattled in cabinets, dogs began to bark, and somewhere in a quiet suburban kitchen, a woman pressed her hand against a trembling wall, wondering if this was finally the one.

For more than a month, the San Francisco Bay Area has endured a relentless barrage of earthquakes—hundreds of small, sharp jolts that refuse to stop.

The ground speaks in bursts now, and no one knows when it will fall silent.

Why is one of America’s most populated regions suddenly shaking without pause?

What ancient forces have awakened beneath these streets?

And could this swarm be a warning of something far worse to come?

The first tremor arrived before dawn on November 9th, 2025.

Residents of the East Bay suburbs woke to a magnitude 3.8 earthquake centered beneath San Ramon.

Most rolled over and went back to sleep, having felt earthquakes before, but this was different.

Within hours, another struck, then another.

By the end of the first week, more than 80 earthquakes of magnitude 2 or greater had rattled the region.

According to the US Geological Survey, the swarm stretched from the quiet neighborhoods of Danville to the hillsides above Gilroy, a seismic fingerprint spreading across the landscape.

The Bay Area sits astride one of the most dangerous plate boundaries on Earth.

Here, the Pacific Plate grinds past the North American Plate at approximately 46 mm per year—the rate at which a human fingernail grows.

This relentless motion has shaped California for 30 million years, but the motion is never smooth.

It builds in silence, accumulating strain across networks of faults until something gives.

On December 19th, the swarm intensified.

An 18-earthquake sequence struck in rapid succession, the largest reaching magnitude 4.0.

The jolt was felt across three counties, and emergency services received hundreds of calls, yet the ground would not rest.

For the residents of San Ramon and Danville, the experience of an earthquake swarm is profoundly different from a single large quake.

There is no definitive moment of crisis, no clear beginning or end.

Instead, there is only the slow erosion of certainty, the gnawing awareness that the next tremor could come at any moment.

At 7:41 p.m. on that December evening, a 2.5 magnitude earthquake shook the East Bay.

Fifteen minutes later, a 4.0 struck, then a 3.8, then another—seven earthquakes in less than an hour.

Each one a reminder that the Earth has its own schedule.

The psychological toll is significant.

Sleep becomes fragmented, conversations pause mid-sentence as people wait for the shaking to pass, and children ask questions their parents cannot answer.

Scientists explain that earthquakes often arrive in clusters because stress along a fault does not release uniformly.

When one section slips, it transfers pressure to adjacent segments, sometimes triggering additional ruptures.

The process can continue for days, weeks, or even months.

But knowing the science does not make the shaking easier to bear.

Chapter 1: The Nature of Swarms

What separates routine rumbling from rising danger?

That question haunts every seismologist studying the Bay Area.

An earthquake swarm differs fundamentally from a typical seismic sequence.

In most cases, a large main shock is followed by smaller aftershocks that gradually diminish over time.

The pattern is predictable, and the energy release measurable.

Swarms follow no such rules.

In San Ramon, more than 150 earthquakes occurred in the weeks following November 9th.

The tremors did not decay; they waxed and waned, surging without warning.

One week brought silence; the next brought dozens of jolts in a single day.

The US Geological Survey defines a swarm as a series of earthquakes clustered in space and time without a clear main shock.

The events may be similar in magnitude, making it impossible to identify which tremor, if any, was the dominant rupture.

Since 1970, the San Ramon region has experienced at least 10 major swarms.

In 2015 alone, more than 4,000 seismic events were recorded over 36 days, including nine earthquakes above magnitude 3.

Scientists at UC Berkeley’s seismology lab documented the sequence in detail, mapping the migration of ruptures across three distinct fault segments.

And yet, none of these swarms preceded a major earthquake.

The question remains unanswered: Are swarms a warning or a release valve?

Chapter 2: The Faults Beneath

The San Andreas Fault is the most famous fracture in North America, but it is not alone.

Beneath the Bay Area lies a tangled web of interconnected faults, each capable of producing damaging earthquakes.

The Hayward Fault runs 74 miles through densely populated cities from San Jose to San Pablo Bay.

The Calaveras Fault branches off near Hollister and extends north through Morgan Hill, Pleasanton, and into San Ramon.

In 2007, scientists at UC Berkeley discovered that the Hayward and Calaveras faults merge at a depth of approximately 6.4 km.

This connection has profound implications.

If both faults ruptured simultaneously, the resulting earthquake could exceed magnitude 7.3.

The current swarm is concentrated on the northern segment of the Calaveras Fault, where it intersects with the Concord-Mount Diablo Fault Zone.

This junction creates a complex structural environment where stress concentrates and releases in unpredictable bursts.

The Pacific Plate does not pause; every year it slides another 46 mm northwest, loading more energy onto these fractures.

Scientists monitor every tremor, but they cannot predict what comes next.

Understanding the difference between swarms and aftershocks is essential for assessing risk.

The distinction shapes evacuation decisions, building inspections, and public communication.

Aftershocks follow a main shock; they decay over time according to well-established statistical patterns.

Emergency managers can estimate how many will occur and roughly when.

Swarms offer no such clarity.

The earthquakes beneath San Ramon include elements of both phenomena.

Some tremors appear to trigger others in traditional aftershock sequences.

Others arrive independently, driven by deep processes that remain poorly understood.

One leading hypothesis involves the migration of pressurized fluids through fractured rock.

As water or gas moves through the crust, it can reduce friction along fault surfaces, allowing ruptures that might otherwise remain locked.

This mechanism has been observed in volcanic regions and geothermal areas worldwide.

San Ramon has no volcanoes, but the complex fault intersections beneath the East Bay may create conditions where fluid movement plays a role.

Chapter 3: The Accumulation of Strain

The uncertainty is itself a hazard.

Without clear patterns, scientists cannot issue confident forecasts.

Why has the ground chosen this moment to speak?

The answer lies in the physics of plate boundaries.

For millions of years, tectonic forces have compressed and sheared the rocks beneath California.

Energy accumulates along locked fault segments, building year after year until the strain exceeds the strength of the rock.

When that threshold is crossed, the fault slips.

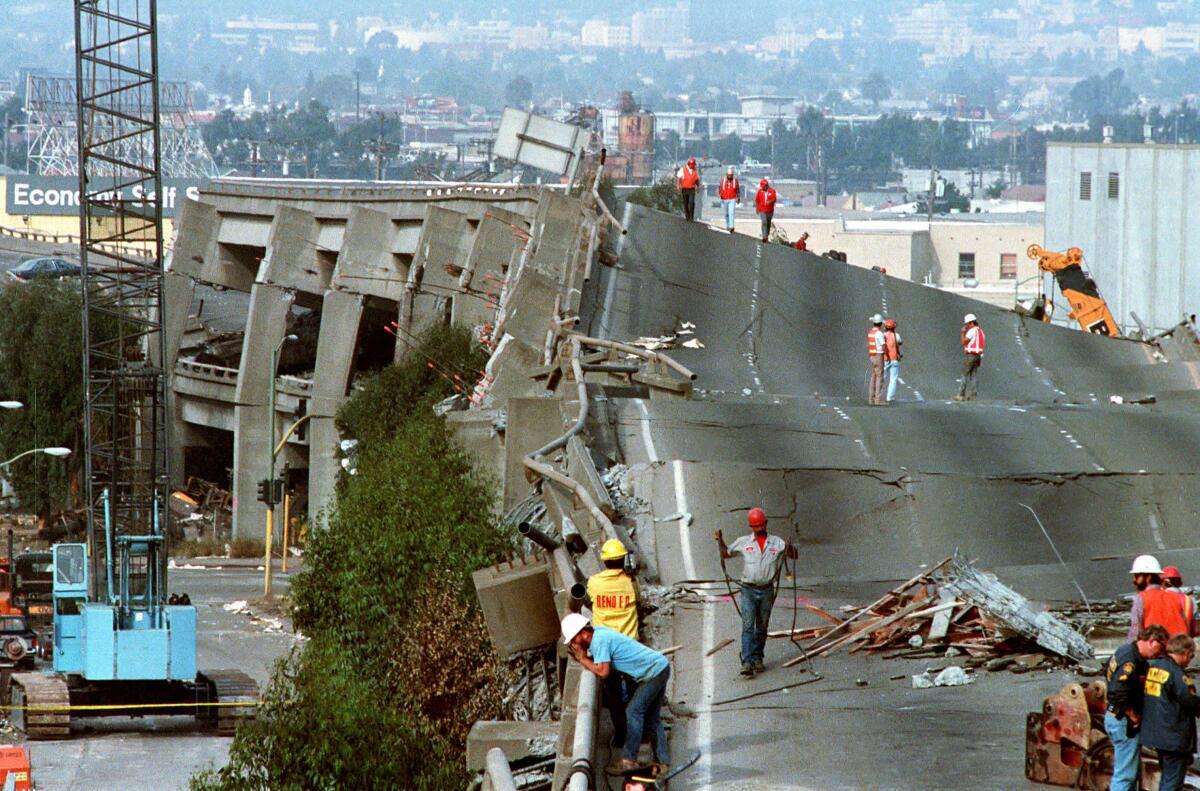

The Calaveras Fault has not produced a major earthquake on its northern segment since 1861, when a tremor estimated at magnitude 6.9 ruptured the ground between the Amador Valley and Danville.

For more than 160 years, the fault has remained relatively quiet.

But quiet does not mean inactive.

GPS measurements show that strain continues to accumulate across the region at rates consistent with long-term plate motion.

The locked segments of the Calaveras and Hayward faults store immense amounts of elastic energy, waiting for release.

Scientists at the USGS estimate there is a 72% probability of at least one earthquake of magnitude 6.7 or greater striking somewhere in the Bay Area before 2043.

The Hayward Fault alone has a 31% chance of producing such an event.

The current swarm may release a small fraction of that accumulated stress, or it may have no effect at all on the larger seismic picture.

Tectonic motion never pauses; the countdown continues.

Beneath the suburban streets of San Ramon lies a geological architecture more complex than most residents imagine.

Faults are not simple cracks; they are dynamic systems with multiple plays, stepovers, and intersecting fractures.

The 2015 swarm illuminated three parallel fault zones beneath the East Bay, each striking southwest and dipping to the northwest.

These structures transfer slip from the northern Calaveras Fault to the Mount Diablo thrust in the Concord Fault system.

The process resembles a chain of dominoes.

When one segment moves, it redistributes stress to adjacent fractures, potentially triggering additional ruptures.

Small earthquakes may dissipate energy through countless tiny slips, preventing larger accumulations.

Alternatively, they may destabilize locked sections, pushing the system closer to catastrophic failure.

Current science cannot distinguish between these possibilities in real-time.

Each swarm becomes a laboratory for studying fault behavior.

Each tremor reveals new details about the hidden structures below.

But prediction remains beyond our grasp.

Chapter 4: The Historical Context

Millimeters of motion translate into massive consequences.

The silence between quakes is merely temporary.

The earthquake swarms beneath San Ramon are not unprecedented.

History offers both comfort and warning.

Since 1970, at least 10 significant swarm events have occurred in this region.

They have lasted anywhere from 2 days to 42 days, with maximum magnitudes generally ranging from 3.0 to 4.0.

None has directly preceded a major earthquake.

In 2003, hundreds of small tremors rattled the same neighborhoods now experiencing the current sequence.

The swarm faded without escalation.

In 2015, more than 4,000 events were recorded.

Again, the ground eventually fell quiet.

But foreshocks do sometimes precede major ruptures.

In 1857, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake ruptured 225 miles of the San Andreas Fault in Southern California.

Witnesses reported unusual seismic activity in the days before.

In 2011, the devastating magnitude 9.0 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan was preceded by a foreshock sequence.

The challenge is that only about half of major earthquakes have identifiable foreshocks.

The other half arrive without warning.

Scientists cannot yet distinguish a swarm that will fade from one that signals catastrophe.

Preparation remains the only reliable defense.

Chapter 5: Monitoring and Preparedness

Beneath the Bay Area, a vast network of sensors monitors every tremor in real-time.

The USGS Northern California Seismic Network operates hundreds of stations across the region, recording ground motion with extraordinary precision.

Modern seismometers can detect earthquakes too small for humans to feel, sometimes below magnitude 1.0.

Algorithms analyze the data within seconds, triangulating location and depth, identifying patterns that might escape human observation.

The Shake Alert earthquake early warning system represents the cutting edge of this technology managed by the USGS.

It can detect the initial P-waves of an earthquake and issue alerts before the stronger S-waves arrive.

Seconds of warning can allow people to take cover, trains to slow, and gas valves to close.

But Shake Alert cannot predict earthquakes; it can only announce them after they begin.

The current swarm has triggered no unusual alerts from the monitoring network.

The earthquakes fall within the range of historical activity for this fault zone.

Scientists describe the sequence as consistent with past events.

Yet, the data cannot reveal what happens next.

Interpretation matters more than raw numbers.

The swarm continues, and the sensors keep watching.

Chapter 6: The Human Experience

On a quiet street in San Ramon, a woman stands at her kitchen window each morning, waiting to see if the pictures will shake again.

Her name is Lisa, and she has lived in this house for 12 years.

The first earthquake woke her at 3:00 a.m.

She heard the blinds rattle and felt the floor tremble beneath her feet.

By the fourth tremor that week, she found herself shouting at the walls, demanding the shaking stop.

Her neighbors share similar stories.

Emergency kits have appeared in garages, and families discuss evacuation routes over dinner.

Children have learned to duck and cover at school.

“You get to the point where you just wonder, ‘Okay, are we done yet?’” she told a local reporter, exhaustion evident in her voice.

The psychological weight of repeated tremors is difficult to measure but impossible to ignore.

Sleep deprivation compounds anxiety, and uncertainty erodes the sense of home as a place of safety.

Emergency officials urge preparedness without alarm.

They distribute information about securing heavy furniture, maintaining water supplies, and registering for alert systems.

But no amount of preparation can eliminate the fundamental vulnerability of living atop an active fault.

The community endures, and the shaking continues.

Resilience becomes a daily practice.

Every swarm that passes without disaster becomes data for the next generation of scientists.

Each sequence teaches something new about fault behavior, stress transfer, and the hidden mechanics of the crust.

The current events beneath San Ramon are already being analyzed by researchers at UC Berkeley, the USGS, and universities around the world.

Their findings will refine hazard models, improve building codes, and inform emergency planning for decades to come.

But the Earth does not reveal its secrets easily.

Despite more than a century of seismological research, no reliable method exists to predict exactly when or where a major earthquake will strike.

The forces involved operate on time scales and spatial dimensions that resist precise measurement.

What scientists know is this: the Bay Area will experience a damaging earthquake again.

The Hayward Fault has ruptured approximately 140 times throughout recorded history.

The last major event occurred in 1868, more than 150 years ago.

The clock is ticking.

The swarm may fade tomorrow or persist for months.

It may have no connection to future large earthquakes, or it may be a whisper of forces gathering in the deep.

Current science cannot say with certainty.

What remains is the enduring mystery of coexistence with a restless planet.

The ground beneath our feet holds memories of catastrophes past and secrets of disasters yet to come.

More than 7 million people now call the Bay Area home.

They live and work above fault systems that have shaped this landscape for millions of years and will continue reshaping it long after human memory fades.

The silence between earthquakes is not peace; it is accumulation.

And somewhere beneath San Ramon, the pressure continues to build.

News

😱 ICE & FBI STORM Minneapolis – $5B Fraud & Somali DAYCARE Director EXPOSED 😱 – HTT

😱 ICE & FBI STORM Minneapolis – $5B Fraud & Somali DAYCARE Director EXPOSED 😱 The landscape of technological innovation…

😱 Last Moments of Kianna Underwood from All That – The Tragic Hit-and-Run That Shocked Fans 😱 – HTT

😱 Last Moments of Kianna Underwood from All That – The Tragic Hit-and-Run That Shocked Fans 😱 The story of…

😱 What Scientists Just FOUND Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Will Leave You Speechless 😱 – HTT

😱 What Scientists Just FOUND Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Will Leave You Speechless 😱 Deep beneath the ancient streets…

😱 Is This What Jesus Really Looked Like? AI’s Stunning Reconstruction from Ancient Artifacts Revealed! 😱 – HTT

AI Reconstructed the Face of Jesus From Ancient Relics — and It Shocked the World For centuries, the image of…

😱 The Dark Secrets of The Passion of the Christ: Mel Gibson Finally Opens Up About the Film’s Haunting Legacy! 😱 – HTT

Mel Gibson Finally Admits the Truth about The Passion of the Christ: A Journey of Faith, Pain, and Redemption In…

😱 Divine Signs or Just Tricks of the Light? 20 Times Jesus Christ Was Captured on Camera That Will Make You Question Everything! 😱 – HTT

20 Times Jesus Christ Was Caught on Camera: A Journey Through Faith and the Unseen In a world where the…

End of content

No more pages to load