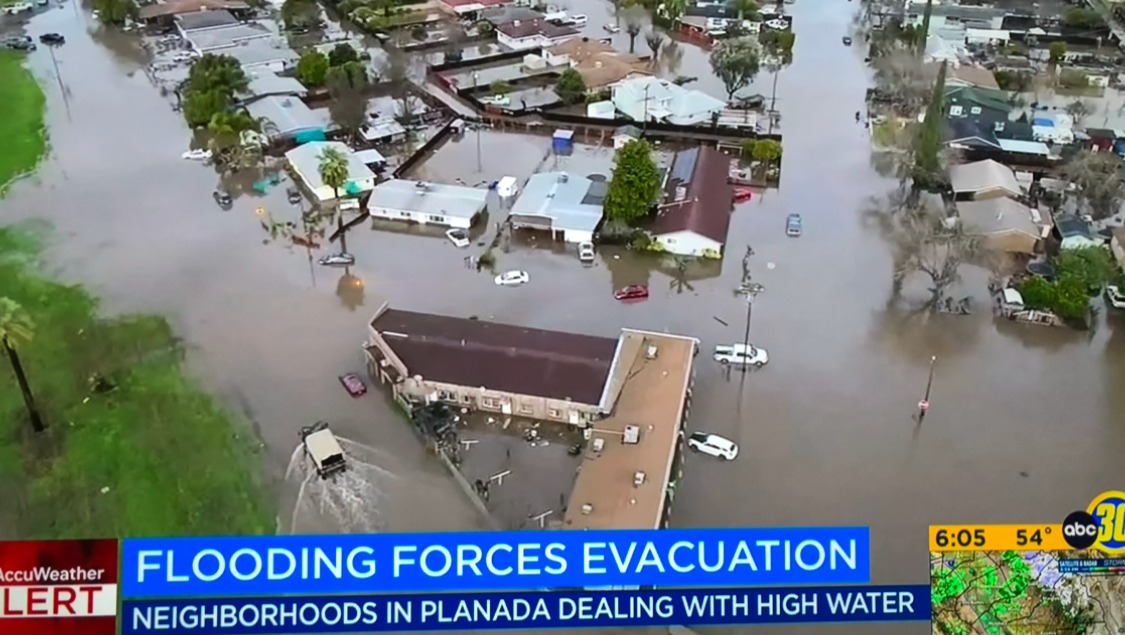

😱 NO ONE BELIEVED The Warnings Until Central Valley Footage Proved It – Scientists Issue Warning 😱

NO ONE BELIEVED the warnings until Central Valley footage proved it—scientists issue urgent warnings.

Fields full of perfectly good produce are going largely unharvested this holiday season.

One farmer tells us that the ramped-up immigration raids across the country are scaring workers away from this year’s harvest.

Beneath the endless blue dome of a California sky, the horizon stretches golden and green toward distant blue mountains.

This is the Central Valley, where the ground once seemed as reliable as the sunrise.

Yet recent footage and data have revealed a landscape in quiet crisis, a hidden catastrophe that’s toppling assumptions as surely as it buckles roads and cracks the foundations of homes.

What you are about to hear is not the aftermath of fires sweeping the coast or floods rushing downhill after a winter storm.

This is much slower, more invisible, and no less dramatic.

It is the story of what happens when the very ground begins to sink, when the foundation for everything above it—from crops to homes to the promises of tomorrow—quietly drops away.

In the past 16 years, time itself seems to have bent.

According to Stanford’s 2025 research, the valley has lost as much ground—much vertical drop—as it did during the entire 50 years prior.

Not millimeters, not inches, but feet.

Entire communities, aqueducts, and fields have subsided in the span of a single generation.

This is not the work of wind and rain, nor the gradual drift of tectonic plates deep underground.

Something else is at work—something vast and accelerating, transforming the bedrock of California’s agricultural life.

Recent satellite images display the scars: canals warped, fields furrowed into uneasy patterns.

Dry wells, once the lifeblood of rural homes, stand useless beside stacks of bottled water under a blistering sun.

California is no stranger to disaster—the crackle of wildfires scorching Los Angeles hills, the aftershocks of earthquakes trembling through San Ramon.

But none of those prepared the valley’s communities for the silent storm below their feet.

What do you do when the ground itself cannot be trusted?

What happens to a place and its people when the aftermath is not fire or flood, but the slow, relentless vanishing of the land itself?

How did we arrive at this point?

And is there any way back?

For generations, the Central Valley’s abundance has been a kind of miracle.

Over 20,000 square miles transformed into a powerhouse of agriculture worth billions—tomatoes, almonds, grapes, leafy greens—food not only for the country but much of the world.

All conjured from soil that owes its fertility to ancient water flowing unseen beneath the surface.

Decades ago, when engineers built the California aqueduct and the state water project, the future looked defined and manageable.

Water would travel in concrete channels from the north into a thirsty, sunlit south, and wells could be dug when nature failed to supply.

Orchard by orchard, acre by acre, this hidden choreography of surface water and groundwater supported a region that came to feed a continent.

The aquifer system is massive—a natural sponge forming over millions of years.

Not underground lakes, but networks of sand and clay—the spaces between particles saturated by rain and ancient snowmelt.

Water drawn up in a healthy cycle, winter rains replenishing what summer harvests required, kept this underground world resilient.

Clay layers compressed when water was pumped, then rebounded when aquifers refilled—a quiet elasticity that made everything above possible.

Climatologists, hydrologists at the USGS, and generations of farmers understood those rhythms.

Even as pumping increased in the 20th century, the land’s slow, measured settling—up to 28 ft over 50 years—remained at least predictable.

When the state water project launched in the 1970s, the system stabilized.

A balance was struck.

The valley showed the world what sustainable farming could look like, even in a place built largely on redirected water.

But then the world changed.

In 2006, California entered an extended drought—a break in the natural cycle so severe it shattered the pattern.

With rivers empty and reservoirs dust dry, the only option left for most farmers was to turn on the pumps.

Every gallon withdrawn became another unseen subtraction.

Did anyone then imagine that the invisible could become inevitable?

From hundreds of miles above Earth, satellites watched what eyes on the ground could not.

Interferometric synthetic aperture radar, INSAR for short, allowed researchers to track the valley’s rise and fall with striking precision.

What these orbiting sentinels observed—confirmed by ground-based GPS stations and extensometers sunk deep into the Earth—was the land itself folding, compressing, and subsiding at a rate few had anticipated.

Between 2006 and 2022, the Central Valley dropped by about 14 cm—almost as much as the collapse measured from 1925 to 1970.

In places, the ground has been dropping by more than a foot per year.

Consider a house losing its footing bit by bit.

Envision a canal engineered to deliver life-giving water now forming bowls where water pools unable to flow, threatening deliveries for millions.

The footage tells the story.

From above, the aqueduct shimmers—not a single unbroken artery, but a broken series of basins.

Engineers call these distortions “bowls”—places where the sinking of land outpaces the canal’s ability to function.

Water, instead of moving freely, sits motionless, evaporating into the dry air.

Operators, the men and women whose job is simply to get water from point A to point B, find themselves pushing the system to its limits, with water nearly cresting the lip of aging concrete.

Elsewhere, the Friant-Kern Canal, the valley’s workhorse, has lost about 60% of its capacity in subsidence-affected stretches.

Images of the canal show it straining against warped ground—the cost of repair measured not only in dollars—over $400 million and counting—but in the opportunity lost for every growing season.

And beyond the infrastructure, the footage multiplies: dry, abandoned wells dot the land.

Over 4,200 homes reported hauling water to survive, though the actual number is certainly higher as many families leave or do not formally report their loss.

Farmers, those first to feel such shifts, have drilled thousands of new wells in just the past several years—all sunk deeper than the last.

In some places, they are now reaching water that fell as rain thousands of years ago—long before there was a state or a valley, before anyone named these rivers or tilled these fields.

What is the cost of survival when every drop pulled from the ancient past draws the ground a little farther from the present?

What Stanford’s modeling and the unrelenting drop in ground level have revealed is a process unlike what planners had imagined.

At the surface, when you pump water, the sand and gravel layers act like a sponge—squeezed and released, returning nearly to their former shape when water returns.

But farther down lie the deep clay layers, and here the story changes.

Clay does not forgive.

Compress it, and the space between particles closes forever, fusing into a dense, compacted layer unable to bounce back.

Stanford’s 2024 research is clear: over 90% of current subsidence comes from deep clay layers.

Unlike the sand and gravel, once this storage is lost, it is lost for good.

Even if all wells stopped pumping tomorrow, even if winter rains and Sierra snowpack returned in force, the compaction would continue for decades—generations, even centuries.

Stanford’s 2025 modeling projects this sustained sinking, forecasting a future where the land subsides long after any meaningful action could be taken to stop it.

The footage from the air shows more than just geometry or physics; it is the visual language of irreversible change.

Roads cracked not only by weather or neglect, but by a foundation slipping steadily away.

Bridges that no longer meet the ground at their ends.

Fields warped into new uneasy slopes.

The soil’s memory rewritten.

Managed aquifer recharge—deliberately flooding fields during wet years to try to refill aquifers—stands as the final desperate corrective.

But the math refuses to cooperate.

There is simply not enough water.

The Sierra Nevada’s snowpack, along the state’s natural reservoir, has diminished amid shifting climate patterns.

Even during generous years, surplus water falls far short of what is needed to reverse decades of drawdown, let alone refill layers of clay that will never regain their original capacity.

And even if more water were available, most recharge goes to sandy layers, not to the deep compacted clays.

The damage done there is largely permanent.

Water may simply bypass the critical storage zones or pool above clay that will not loosen its grip.

California’s legislative response to years of failed wells and crumbling infrastructure arrived in 2014—the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA—a framework for local control, science-based targets, and clear timelines.

Agencies across the valley drew up plans guided by the hope that stabilizing water levels would stop the sinking and restore balance.

But Stanford’s models undercut this hope.

The damage in the clay is already done and will continue unfolding for decades regardless of water management at the surface.

The land will keep collapsing—a conclusion as implacable as geology itself.

Footage shows another side of the story: meetings in dusty government offices, exhausted hands clutching maps showing subsidence rates.

County officials face impossible choices.

Kings County, among the hardest hit, was cited for an inadequate groundwater plan.

Their response was devastating in its frankness: “We have no other economy.”

Kings County becomes a ghost town.

Such choices take a human toll.

Fields left, tractors sold, and communities gradually erased from maps.

Managed recharge means laying aside farmland—an act indistinguishable from economic suicide for those whose livelihoods depend on every acre.

The trap is perfect.

The land collapses because of overpumping.

To stop pumping is to sacrifice jobs and traditions.

To return to balance would require water that simply isn’t there anymore.

Repairing infrastructure is little more than a temporary bandage.

The California aqueduct damages run into the billions of dollars.

Each fix lasts only until the ground below subsides again.

New deeper wells cost more than $1 million each.

The wait to drill is now longer than a growing season.

And the water reached at these depths is fossil water—last deposited when mammoths still roamed the Earth.

Here, every act of adaptation is a zero-sum game.

One farmer’s deeper well means another’s runs dry sooner.

The phenomenon spreads—rural tragedy repeating itself as each individual decision pushes the valley closer to systemic collapse.

What is the price of survival measured against the loss of the ground itself?

With every new satellite, every technological leap in observation, the scope of the crisis grows.

More precise INSAR imaging reveals subsidence—even in places once thought stable, the affected area grows.

Ironically, the more closely we monitor, the more we learn that few places truly are immune.

Deep well drilling, once a stopgap, drives compaction in the clay layers, making matters worse.

Years of deep pumping were never meant to be normal operating practice.

Yet now, fields are lined with new wells, some as deep as 2,000 ft, tapping water left in the ground back when the world was younger.

Each withdrawal depletes storage and hastens subsidence.

The numbers paint a stark reality: the valley produces about 80% of the world’s almonds and 95% of America’s processed tomatoes.

If production falters, food prices can shift worldwide.

What began as a regional emergency passes through every link of the global food supply.

Urban California rides on the same fragile infrastructure.

A 2025 projection indicates the valley, which once provisioned America’s kitchens with fresh food, may soon struggle to serve even its own communities.

And at each turn, the question remains: how much longer can this improvisation last?

Every solution narrows the options for someone else.

Larger growers, those with more capital, drill ever deeper wells and invest in efficient irrigation.

Smaller farmers, those with thin margins and the most to lose, fall by the wayside, unable to afford the cost.

Managed recharge remains out of reach.

Land and financial resources are scarce.

Some local water agencies choose triage—fixing the aqueducts and main canals, letting other less strategic areas slide.

This too shows in the satellite images.

From above, infrastructure may gleam, but neighborhoods at the edges languish—parched, emptied, left to bear the brunt as the ground continues its quiet but relentless fall.

These families are forced to haul water, borrow from neighbors, or abandon their homes altogether.

With no resources to pay for deeper wells, there are no backup plans.

Footage from these towns tells the story: empty trailers, shuttered corner stores, and playgrounds beside houses where water no longer flows.

This new migration is written not in headlines but in departures noted quietly in empty lots and shuttered schools.

And as always, the less powerful bear the greatest risks.

Those who contributed least to the overpumping and enjoyed the smallest share of past prosperity are now left with the heaviest losses.

Environmental justice as policy and principle confronts the hard, immovable arithmetic of geology and economics.

The rules, shaped by law and guided by science, often favor those who can afford to comply.

SGMA’s mandates to reduce groundwater pumping fall first and hardest on regions with scant access to alternative supplies.

The valley’s poorest counties are told to bear the largest sacrifices so the broader system might endure, even as the local reality retreats.

The unspoken question at every council meeting and water agency session: can a region built on plenty survive when the rules of survival no longer match its resources?

Climate change, ever-present, accelerates every underlying trend.

The Sierra Nevada, California’s snow-fed reservoir, shrinks year after year.

Droughts, once cyclical, now come with increasing frequency.

The exceptional has become the new ordinary.

Each dry year sends groundwater use soaring.

Each new well deepens the wound.

Canals seen from above snake through a buckling landscape, their engineered angles thrown off by subsidence.

Engineers struggle to maintain flow or patch problems as best they can—always short of a long-term fix.

Nick, with each passing year, the feedback tightens: drought leads to pumping, pumping drives subsidence, subsidence breaks infrastructure, broken aqueducts cut off surface water, and drought pressures return.

And the cycle begins again.

The system, once resilient, moves further from recovery.

Research on worldwide aquifer withdrawal reveals that California’s challenge is not unique.

Across the planet, ancient underground water reserves are vanishing faster than they can be replaced.

The deep clay will continue to settle for generations.

The system cannot recover because, in a fundamental sense, its capacity to recover is gone.

The ground beneath the Central Valley—beneath America’s supermarket—has dropped as much as 28 ft in a century.

In the last 16 years, it has collapsed as much as it did during the entire half-century before that.

This is no longer just an abstraction or a problem waiting for some technological fix.

It is the daily reality for people living atop an environment whose rules have changed.

Canals and reservoirs, triumphs of 20th-century engineering, now rest on land that shifts continually.

Repairs are temporary, buying time more than restoring function.

Communities fade, not to fire, quake, or flood, but to the slow undoing of the very ground below.

Stanford’s research, together with observations from NASA’s satellites and federal fieldwork, reveals a future of declining storage, vanishing potential, and aquifers incapable of bouncing back.

If the climate delivers more drought and water policy only delays the consequences, the outcome may be unavoidable.

There are no obvious villains here.

Farmers drilled wells to keep their crops alive.

Agencies wrote plans using the best information at the time.

Engineers maintained infrastructure with heroic resolve.

Every step for years and decades seemed reasonable until the ground beneath those steps shifted, both literally and figuratively.

Now the questions verge on existential: can we feed America and the world on land that is physically subsiding?

What will food prices look like if California’s production falters?

Will water run down the aqueduct in 20 years?

Or will it stagnate above land that keeps moving out from under it?

And what fate lies ahead for the ancient clay a mile beneath our feet?

A foundation that bends to no policy, promise, or plan.

In the end, nobody quite expected this aftermath.

Not the planners who charted decades of resilience.

Not the farmers who watched their wells deepen year after year, nor the officials confident in temporary stability.

From those first satellite images to the latest cracks in concrete, reality has overtaken memory.

The collapse continues, not as a single tragedy in a single moment, but as a slow cascade, likely to continue for generations.

If there are lessons here, they are sobering ones.

The Earth remembers what’s taken from it.

The clay keeps its own timeline.

Drill the deepest wells, and an irreversible clock begins to tick.

The aquifer that powered California’s epic agricultural miracle—the underground reservoir of possibility—is shrinking, compacting, and diminishing.

Eventually, the wells will go dry, not for lack of water, but for lack of a foundation to store and yield it.

The aqueducts, their concrete bones buckled by the ground beneath, will become relics.

And the horizon, so long green and golden, will shift again.

Where will the almonds, salads, and tomatoes come from then?

Can the valley that helped feed the world still imagine itself as its supermarket when the bedrock is quite literally vanishing?

The footage from California’s Central Valley shows in real-time more than a crisis.

It reveals the shape of loss still unfolding and invites us all to ask, “How much further does the ground have to fall before we understand what’s already gone?”

News

😱 Greg Biffle’s Crash and the Deadly Cluster: Understanding the December Aviation Crisis 😱 – HTT

😱 Greg Biffle’s Crash and the Deadly Cluster: Understanding the December Aviation Crisis 😱 December 2025 was supposed to be…

😱 21,018 Points and No Recognition: The Tragic Story of Alex English! 😱 – HTT

😱 21,018 Points and No Recognition: The Tragic Story of Alex English! 😱 When you think of the greatest basketball…

😱 STEFON DIGGS CHOKED & SLAPPED HER! GORY DETAILS Emerge from Patriots Receiver’s ALTERCATION! 😱 – HTT

😱 STEFON DIGGS CHOKED & SLAPPED HER! GORY DETAILS Emerge from Patriots Receiver’s ALTERCATION! 😱 The New England Patriots find…

😱 “He Should Be JAILED For Life!” Joe Rogan React to Jake Paul Involvement In Anthony Joshua Accident! 😱 – HTT

😱 “He Should Be JAILED For Life!” Joe Rogan React to Jake Paul Involvement In Anthony Joshua Accident! 😱 In…

😱 Two Lives Lost: The Hidden Truth Behind Anthony Joshua’s Devastating Accident! 😱 – HTT

😱 Two Lives Lost: The Hidden Truth Behind Anthony Joshua’s Devastating Accident! 😱 In a shocking turn of events, the…

😱 STEFON DIGGS IN BIG TROUBLE! Faces FELONY STRANGULATION/SUFFOCATION Charge! Patriots NIGHTMARE! 😱 – HTT

😱 STEFON DIGGS IN BIG TROUBLE! Faces FELONY STRANGULATION/SUFFOCATION Charge! Patriots NIGHTMARE! 😱 In a shocking development that could have…

End of content

No more pages to load