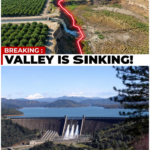

California’s Central Valley Faces Unprecedented Ground Sinking: A Geological Crisis Unfolds!

In November 2024, a groundbreaking study from Stanford University revealed a shocking truth about California’s Central Valley.

Researchers discovered that the land is sinking at an alarming rate—14 kilometers of subsidence in just 16 years.

To put that into perspective, this is the same volume of subsidence that took 50 years to accumulate between 1925 and 1970.

In some areas, the ground is sinking more than one foot per year, raising critical alarms for the 6.5 million people who live and work in this agricultural powerhouse.

The headlines may focus on the immediate damage—cracked infrastructure, buckled roads, and canals losing their flow capacity—but the real story goes much deeper.

The land is not merely sinking because water is being extracted; it is sinking because the space where water once resided can no longer hold water again.

This phenomenon represents a fundamental shift in understanding groundwater dynamics, as the land is now sinking three times faster than historical rates.

The impact of this subsidence is staggering.

The Tari Basin, for example, experiences ground drops exceeding 30 centimeters annually, and near Corkran, total subsidence has reached 28 feet since the 1920s.

An area larger than Connecticut—over 5,200 square miles—has been affected.

The state water project, which serves 27 million Californians, relies on infrastructure built atop ground that is collapsing.

Historically, after new aqueducts were constructed in the 1970s, subsidence rates slowed dramatically.

Water managers believed they had solved the problem, predicting stable conditions if groundwater pumping was regulated.

However, the reality has proven far more complex.

The return of subsidence has exceeded previous rates, leaving scientists and water managers scrambling to understand the implications.

NASA’s InSAR satellite data has illuminated dark red zones spreading across the valley floor, indicating areas of significant sinking.

Each color change represents a 10-centimeter drop, and some regions cycle through the entire color spectrum annually.

While news reports highlight the infrastructure damage—repairs costing hundreds of millions—the true cost lies in the aquifer itself, which cannot be rebuilt.

Stanford’s models indicate that even if pumping were to stop today, the land would continue to sink for 100 to 300 years.

When it finally stabilizes, the aquifer will have permanently lost 30 to 50% of its water storage capacity.

This situation is not merely a consequence of drought forcing farmers to pump more groundwater; it is a manifestation of the acceleration paradox.

Pumping faster to compensate for water shortages ultimately destroys the aquifer’s capacity to store water, creating an exponential feedback loop.

Every gallon of water pumped today guarantees tomorrow’s drought.

California’s Central Valley, stretching 450 miles and covering 20,000 square kilometers, produces over $50 billion annually in agricultural output, accounting for 25% of America’s table food.

The valley sits atop one of the world’s most productive aquifer systems, consisting of three distinct layers.

The shallow aquifer, composed of sand and gravel, allows for quick recharge, while the deeper layers contain ancient water trapped for over 10,000 years.

However, the issue of subsidence stems from a process known as compaction—permanent compression that occurs when water is removed from the aquifer.

InSAR technology measures ground elevation changes with millimeter precision, revealing that 90% of recent subsidence is attributed to deep clay layers below 200 feet.

These layers drain slowly, leading to continued compaction for centuries after pumping stops.

The alarming rate of subsidence—14 cubic kilometers between 2006 and 2022—represents enough lost space to hold 11.3 million Olympic swimming pools.

California has permanently lost the ability to store 3.7 trillion gallons of groundwater, equivalent to the water needs of Los Angeles for 15 years.

The history of groundwater management in California has been fraught with challenges.

From 2000 to 2005, the Central Valley appeared stable, but the shift to permanent crops like orchards and vineyards increased baseline water demand.

Climate changes and surface water deliveries masked the emerging problem, leading to a false sense of security among water managers.

When the drought hit from 2007 to 2009, surface water allocations were cut drastically, prompting farmers to drill deeper wells and pump more groundwater.

The USGS began monitoring GPS stations and detected unexpected vertical movements—land sinking at rates of 4 to 6 inches per year.

Dr. Michelle Sneed of the USGS initially thought they were observing seasonal variations, but the consistent pattern revealed a troubling reality: the land was sinking.

Dr. Rosemary Knight from Stanford noted two astonishing aspects of this subsidence—first, the magnitude of what occurred before 1970, and second, that it is happening again today.

NASA’s continuous InSAR monitoring began in 2011, and during the severe drought from 2012 to 2014, surface water deliveries plummeted.

More than 5,000 new agricultural wells were drilled, many exceeding 1,500 feet, tapping directly into the deep aquifer.

The results were alarming, with some areas experiencing water table drops of over 50 feet in just two years.

Even when precipitation returned between 2015 and 2017, the expected result was a decrease in subsidence.

Instead, subsidence continued at rates of 6 to 8 inches per year.

Researchers Matthew Lees and Rosemary Knight utilized data from multiple satellites and agencies to calculate the total subsidence volume from 2006 to 2022, revealing a stark acceleration factor—subsidence is now occurring three times faster than in the past.

The implications of this research are profound.

The thick clay layers throughout the valley will continue to compact for decades to centuries after water levels stabilize.

The compaction process behaves like a geological capacitor, with water pumped in 2024 not fully compacting until the year 2200 to 2400.

Recent pumping will cause subsidence to continue into the 2300s, meaning we are already committed to centuries of future subsidence.

The Fryant Kern Canal has lost 60% of its flow capacity due to subsidence, and repairs are costly, with estimates exceeding $400 million for just a small section.

The prognosis is grim, as continued subsidence will likely break the canal again.

Water managers recognized the crisis by 2015, and various solutions were proposed.

However, each theory collapsed when tested against the acceleration paradox.

The first solution suggested stabilizing deep aquifer water levels, but the delayed response means this approach would take too long to yield results.

Even if deep pumping stopped, subsidence would continue at 80% of the current rate for 10 to 30 years.

The second solution proposed recharging fields during wet winters, but research shows that deep clay compaction is inelastic, meaning it cannot be reversed.

The third solution focused on reducing agricultural water use, but efficiency improvements have already been implemented, and permanent crops dominate 60% of valley acreage.

Importing more surface water was suggested as a fourth solution, but the costs and timelines make this approach impractical.

The Delta conveyance project, estimated at $16 to $20 billion, would not be operational until the 2040s, while subsidence from past pumping will continue until 2200.

Each proposed solution addresses one aspect of the problem while ignoring others, leading to a cycle of hydraulic whack-a-mole.

Stopping pumping leads to economic collapse, while recharging cannot reverse compaction.

Reducing agricultural water use is negated by the prevalence of permanent crops, and imported water is too slow and costly.

This is not merely a groundwater management issue; it is a geological transformation triggered by human activity that cannot be stopped.

For a century, California treated its aquifer as a water bank, withdrawing and depositing water on timescales measured in decades.

However, aquifers are geological formations that operate on timescales measured in millennia.

We have crossed irreversible thresholds, and now we face the consequences.

The damage is structural and permanent, with clay compaction continuing for 100 to 300 years after pumping ceases.

Even with perfect management starting now, the valley will continue sinking until 2200 or beyond.

As the Central Valley transforms, the implications for agriculture, infrastructure, and the economy are dire.

The question is no longer whether California can prevent subsidence; it is how we manage the next 200 years of consequences we have already committed to.

How do we maintain agriculture when the ground sinks a foot every 3 to 5 years?

How do we communicate to 6.5 million people that the valley they live in is permanently changing?

This situation serves as a warning about the irreversible thresholds we are crossing globally.

If California, with its wealth and expertise, cannot solve a geological problem it created, what does that say about humanity’s ability to reverse ecological transformations on a larger scale?

The Central Valley is not unique; it is a microcosm of the challenges we face as we grapple with our impact on the planet’s geological systems.

News

😱 Tony Stewart’s Shocking Comeback: Is He Ready to Reclaim His NASCAR Glory After 21 Years? 😱 – HTT

Tony Stewart’s Groundbreaking Return to NASCAR: A Shocking Comeback After 21 Years Tony Stewart, a name synonymous with NASCAR, has…

😱 FUNERAL: Cleetus McFarland Breaks Down Honoring Friend Greg BIffle 😭💔 – HTT

😱 FUNERAL: Cleetus McFarland Breaks Down Honoring Friend Greg BIffle 😭💔 In a somber yet uplifting event, the NASCAR community…

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Vesuvius Twin Supervolcano Hits Magnitude 4.4 – 500,000 Trapped in Active Crater 😱 – HTT

The Burning Fields: Campi Flegrei Supervolcano Awakens with a 4.4 Magnitude Quake, Leaving 500,000 Residents Trapped in a Geological Nightmare!…

😱 From Tourist Paradise to Pyroclastic Nightmare: The Shocking Truth Behind Mayon Volcano’s Imminent Eruption! 😱 – HTT

Mayon Volcano on the Brink: A Mega Eruption Might Be Imminent as Thousands Are Evacuated Amidst Pyroclastic Fury! Mount Mayon,…

😱 Mel Gibson’s Shocking Revelation: The Ethiopian Bible’s Astonishing Description of Jesus! 😱 – HTT

Mel Gibson: “Ethiopian Bible Describes Jesus in Incredible Detail And It’s Not What You Think” Hidden for centuries, the Ethiopian…

😱 Neil Diamond’s Heartbreaking Battle: The Truth Behind His Parkinson’s Diagnosis at 84! 😱 – HTT

What Happened to Neil Diamond at 84, Try Not to CRY When You See This Neil Diamond, a name that…

End of content

No more pages to load