California’s Gas Crisis Just Hit Arizona — Here’s What Happened

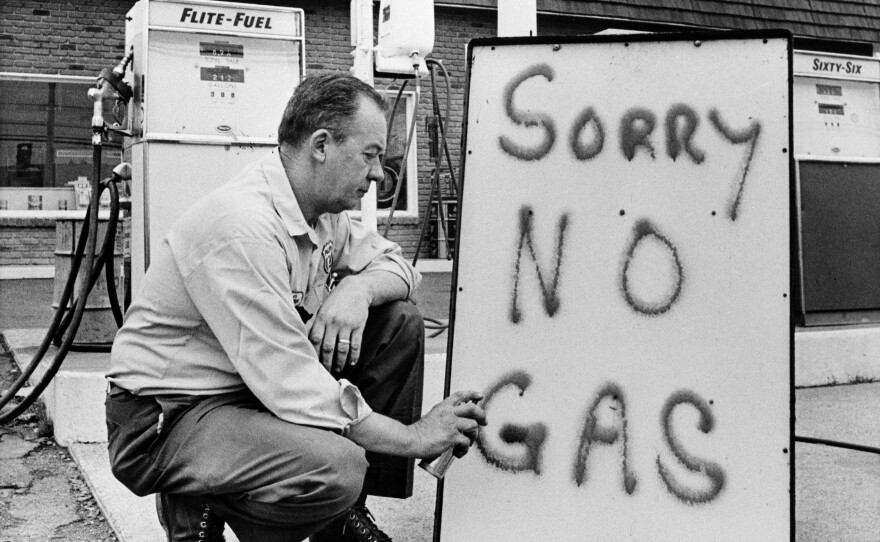

Arizona drivers woke up last week to an unexpected reality.

Gas stations in Phoenix, Tucson, and Flagstaff began posting prices that seemed more in line with California than the Southwest.

By mid-morning, some stations were completely dry, and tanker trucks that typically arrive every two days were suddenly showing up half full or not at all.

This isn’t just a local supply hiccup; this is California’s refinery collapse spilling over state lines in real time.

What you’re about to hear explains how a crisis 400 miles west has become Arizona’s problem too—and it’s getting worse by the day.

California has lost nearly 20% of its refining capacity in less than six months, and now Arizona, which heavily relies on California-sourced fuel, is facing shortages and price spikes that could redefine what drivers pay at the pump across the entire Southwest.

Here’s what’s happening on the ground right now.

Philips 66 shut down its Los Angeles refinery in December 2024, a facility that processed 139,000 barrels of crude oil every single day.

Valero announced that its Benicia refinery will close by April 2026, adding another 145,000 barrels per day to the loss.

Together, these two closures eliminate 284,000 barrels of daily refining capacity, representing 21% of California’s total output.

Additionally, on December 15th, the San Pablo Bay pipeline permanently shut down.

This pipeline carried 100,000 barrels of crude oil daily from Kern County oil fields to Northern California refineries.

The company operating it, Crimson Midstream, was losing $2 million every month and could not sustain those losses, leading to the pipeline’s closure.

California refineries lost their primary crude source overnight, but the damage didn’t stop at California’s borders.

Here’s the part many people don’t understand: Arizona doesn’t produce gasoline.

The state has virtually no large-scale refining capacity of its own.

Arizona relies on fuel supplied primarily from two sources: California to the west and Texas to the east.

When California refineries were running at full capacity, they had surplus fuel to export to neighboring states.

Arizona gas stations, truck stops, airports, and commercial fleets depended on that surplus flowing east through pipeline networks and tanker trucks.

Now, here’s where Arizona enters the picture: there is no surplus anymore.

California is now struggling to meet its own demand, and every gallon produced stays in California.

The fuel that used to flow east into Arizona has been cut off, and Arizona is feeling the squeeze in real time.

Prices at Phoenix pumps jumped 40 cents per gallon in just ten days.

Tucson stations are reporting delivery delays stretching from two to five days, while Flagstaff, which requires a special winter blend gasoline due to its elevation, is facing shortages that force drivers to wait in long lines.

The numbers tell the story clearly.

Arizona consumes roughly 2.3 million gallons of gasoline every single day.

California used to supply approximately 30% of that volume through direct pipeline connections and tanker deliveries—nearly 700,000 gallons per day that Arizona stations could count on.

Now that flow has dropped by more than half, and Arizona is scrambling to find replacement sources from Texas and New Mexico.

But those supply chains weren’t designed to handle this sudden surge in demand.

There are five forces colliding right now that explain why this crisis jumped state lines so quickly.

Let’s break down each one, because understanding the mechanics matters.

First, regulatory pressure in California has made refining unprofitable.

In 2023, Governor Newsom signed SBX12, creating the Division of Petroleum Market Oversight.

This law authorized fines of up to $1 million per day for suspected price manipulation.

Oil companies suddenly found themselves operating under the threat of massive penalties for business decisions that regulators might interpret as gouging.

Then came ABX21 in 2024, mandating strict minimum inventory levels for gasoline and diesel.

Companies were required to maintain up to 16 days of fuel inventory at all times.

While that sounds reasonable, it comes with significant economic implications.

Holding 16 days of inventory necessitates building massive new storage tanks, each costing millions of dollars to construct.

The fuel sitting in those tanks represents capital tied up and not generating revenue.

Insurance costs for storing such flammable material skyrocket, and compliance monitoring requires additional staff and reporting systems for refineries already operating on thin margins.

These costs pushed operations into the red.

Philips 66 announced its Los Angeles closure just two days after ABX21 was signed, and that timing was no coincidence.

Valero followed months later with the same message.

The regulatory environment became untenable, leading companies to choose shutdowns rather than absorb costs that guaranteed losses.

Second, California refineries are old and expensive to maintain.

Many facilities were built in the 1950s and 1960s during the post-war industrial boom.

Equipment that was cutting-edge 70 years ago is now obsolete.

Boilers crack, pipelines corrode, and control systems fail.

Upgrading aging infrastructure to meet modern environmental standards costs hundreds of millions of dollars per facility.

When profit margins are already thin and regulatory threats loom, those capital investments don’t make financial sense.

For example, the Philips 66 Los Angeles refinery would have needed an estimated $400 million in upgrades over the next five years just to maintain current operations—not including expansion or modernization.

When the company ran the numbers against projected revenue under the new regulatory framework, the math didn’t work.

Shutdown became the rational business decision, resulting in 600 full-time workers and 300 contractors losing their jobs.

However, from a pure financial perspective, continuing operations would have cost the company even more.

Third, crude oil supply routes are collapsing.

The San Pablo Bay pipeline closure was the breaking point.

Northern California refineries depended on that pipeline to deliver Kern County crude for 70 years.

The pipeline ran 300 miles from Bakersfield oil fields to Bay Area refineries, transporting 100,000 barrels daily when fully operational.

Without it, refineries must source crude from imports or pay to truck it in, both of which are far more expensive options.

Let’s do the math on trucking: moving 100,000 barrels by truck requires roughly 625 tanker truck trips every single day.

Each truck holds about 160 barrels, meaning 625 trucks would be leaving Bakersfield and driving 300 miles to the Bay Area every 24 hours.

The fuel costs alone for those trucks are staggering, not to mention driver wages, truck maintenance, road wear, and accident risks.

The economic and logistical reality is that trucking cannot replace pipeline capacity at scale.

Some refineries have no viable alternatives at all.

The supply chain that fed California’s refineries for seven decades has effectively died, and there’s no replacement infrastructure ready to take its place.

Fourth, California’s gasoline is unique.

The state requires a special cleaner-burning blend to meet strict air quality standards established by the California Air Resources Board.

This isn’t just marketing; the chemical formulation is genuinely different.

California gasoline has lower Reid vapor pressure, different oxygenate requirements, and stricter limits on sulfur and benzene content.

No other state uses the exact same specifications, which means California can’t easily import gasoline from other regions when shortages hit.

Refineries in Texas or the Gulf Coast produce gasoline that meets federal standards but not California’s requirements.

Importing compatible fuel requires finding specialty refineries or blending facilities that can match California specs, and those are rare.

Most coastal refineries can’t economically justify maintaining separate California blend production lines for the limited export market.

California is functionally isolated from the national fuel supply.

When California’s own refineries shut down, there’s no easy way to replace that lost production with imports.

Fifth, the ripple effect hits Arizona because the Southwest region is deeply interconnected.

Fuel doesn’t respect state borders; pipelines, trucking routes, and distribution networks tie California, Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico together into a single integrated system.

When California’s supply tightens, the entire region feels it immediately.

Arizona stations that relied on California surplus are now competing for shrinking supplies.

Fuel that used to be plentiful is suddenly scarce, and prices respond instantly to supply and demand fundamentals.

Here’s what that looks like on the ground: a gas station owner in Tempe, Arizona, used to receive fuel deliveries every Monday and Thursday like clockwork.

Last week, Monday’s delivery was cut by 40%, and Thursday’s truck didn’t show up at all.

The distributor explained that California refineries are prioritizing in-state customers, leaving Arizona to get what’s left over.

That station owner raised prices by 35 cents per gallon just to slow demand and avoid running completely dry before the next delivery arrives.

Multiply that story across hundreds of stations, and you see how quickly regional supply chains break down.

Let’s walk through three scenarios based on what could happen over the next six to twelve months.

These aren’t predictions; they are possibilities grounded in the data we have right now.

Understanding these scenarios helps you prepare for what might be coming.

Best-case scenario: California manages to stabilize its remaining refining capacity through a combination of emergency regulatory relief and industry cooperation.

The Valero Benicia closure is delayed or canceled after state officials negotiate a temporary exemption from some inventory requirements.

Emergency measures kick in to increase imports from compatible refineries on the West Coast, with Washington and Oregon refineries ramping up California spec production and increasing exports south.

Meanwhile, Arizona negotiates direct supply agreements with Texas refineries and expands pipeline capacity from the Gulf Coast.

New contracts are signed, infrastructure is prioritized, and fuel shipments arrive consistently.

In this scenario, prices spike temporarily but stabilize within three to four months.

Arizona sees prices rise 10 to 15% above historical averages but avoids sustained shortages.

Some rural stations may still face intermittent supply issues, but urban areas maintain steady availability.

Commercial trucking companies absorb higher costs but continue operations, and tourism doesn’t collapse.

Life continues with some financial pain, but no major disruptions to daily routines or economic activity.

This scenario requires several things to go right simultaneously, including flexibility from California regulators, investment from oil companies in workarounds, spare capacity at Texas refineries, and prioritized deliveries from pipeline operators.

All of these elements need to align within a narrow time window—possible but not probable without coordinated action from multiple state governments and private companies.

Base-case scenario: California’s refinery closures proceed exactly as planned.

Valero Benicia shuts down in April 2026 as announced, and Philips 66 in Los Angeles remains closed permanently.

California imports increase modestly but cannot fully replace lost capacity because compatible refineries are already running near maximum output.

Shipping crude and refined products from Asia and Canada increases, but those supply chains take months to scale up and remain vulnerable to global market disruptions.

Arizona faces intermittent shortages, especially during peak summer driving season when demand surges and heat reduces refinery efficiency.

Some rural gas stations may run dry for days at a time during holiday weekends, while urban stations raise prices aggressively to ration supply.

Arizona could see sustained price increases of 25 to 35% compared to 2024 averages, with diesel prices spiking even higher due to global demand competition.

Some small trucking operators may go out of business because they can’t pass fuel costs through to customers fast enough.

Delivery times for goods may stretch longer, and grocery prices could tick up as transportation costs rise.

Tourism revenue in Arizona may drop as travelers from California cancel trips due to their own fuel costs.

Economic activity could slow measurably as fuel costs eat into consumer and business budgets, leading to a new normal that is not a temporary crisis.

Arizona would adapt by importing more from Texas, but it would take time to build out those supply routes.

Prices would remain elevated indefinitely due to the unresolved structural supply deficit, leading people to adjust their driving habits and businesses to relocate operations closer to customers to cut fuel use.

Quality of life would degrade incrementally but noticeably.

Worst-case scenario: Multiple catastrophic factors converge at once.

Another California refinery could experience an unexpected shutdown due to fire, equipment failure, or financial collapse.

Let’s say the Marathon Martinez facility, which is already struggling with profitability, shuts down suddenly, removing another 150,000 barrels per day from the market.

Import capacity from Asia and Canada may not scale fast enough to fill the gap because global refining capacity is tight and tanker rates are spiking.

At the same time, a geopolitical disruption could affect crude oil shipping lanes in the Pacific.

Perhaps tensions escalate in the South China Sea, causing shipping insurance rates to triple, or a hurricane damages port facilities in Long Beach, or a labor strike shuts down West Coast terminals.

Any of these events could choke off the import lifeline California is desperately trying to build.

Arizona’s fuel supply could drop below critical thresholds, prompting governors to declare energy emergencies.

State authorities might implement fuel rationing for commercial and civilian use, prioritizing emergency services, hospitals, and food distribution.

Everyone else would receive limited rations, and prices in Arizona could surge 40% to 60% or higher compared to pre-crisis levels.

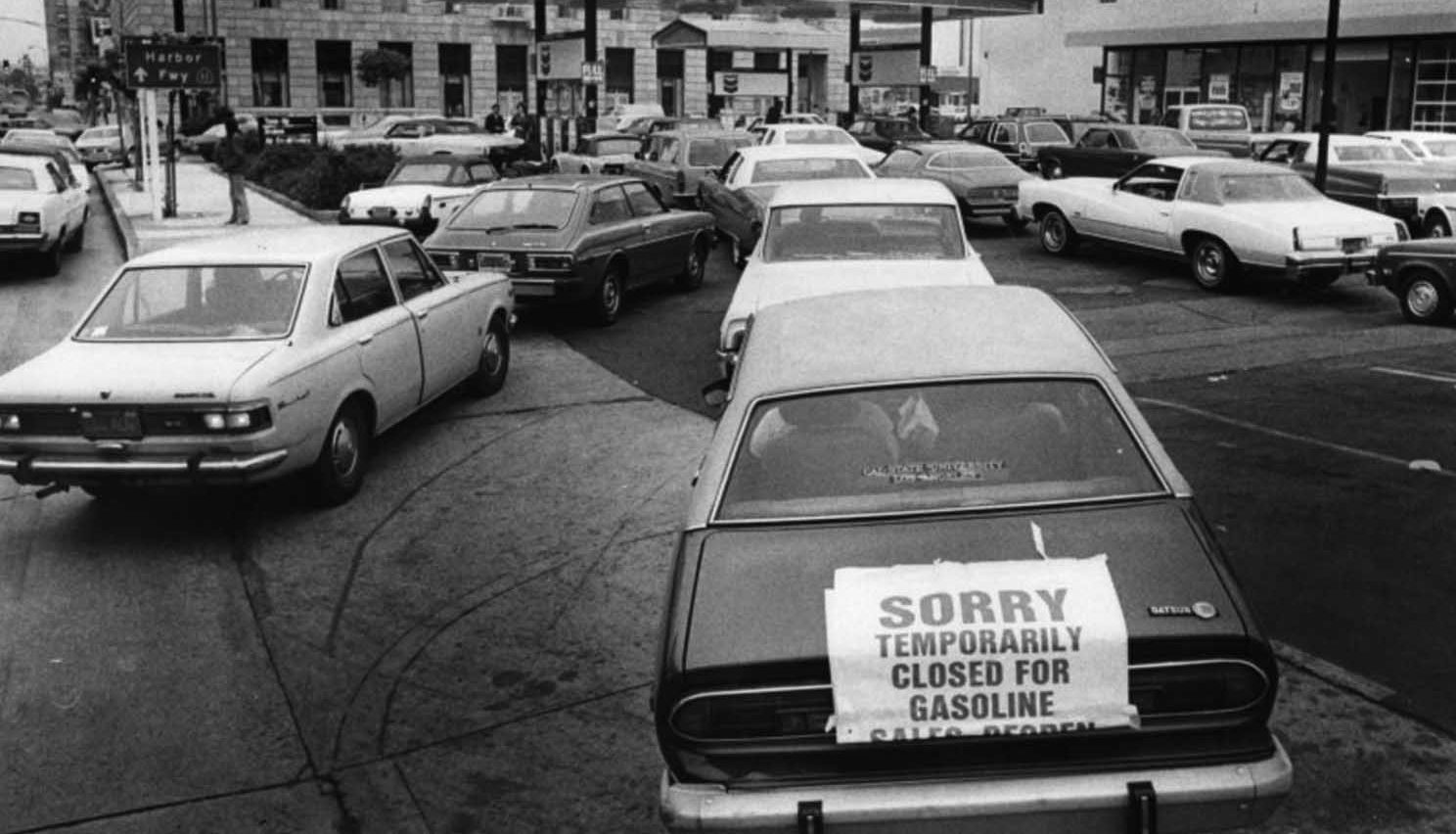

Gas lines would form at stations that still have fuel, and some stations might close entirely because they can’t secure supply at any price.

Businesses would curtail operations dramatically, and non-essential travel might stop altogether.

Airlines could cancel flights out of Phoenix and Tucson due to jet fuel shortages, leading to tourism collapses, canceled conventions, and hotel layoffs.

The Arizona economy could contract sharply, and remote work may become mandatory for anyone who can do it—not by choice, but by necessity.

This scenario sounds extreme, but it is not implausible.

Every element described has historical precedent.

The 1973 oil embargo created gas lines and rationing across America, and the 1979 energy crisis did it again.

Both times, the triggers were geopolitical supply shocks combined with domestic refining constraints.

The Southwest is now more vulnerable than it was in the 1970s because refining capacity is lower and dependence on a few critical facilities is higher.

Which scenario unfolds depends on decisions made in the next few months by refiners, regulators, and regional governments.

Right now, momentum is pushing toward somewhere between the base case and worst case.

The best case requires coordinated intervention that hasn’t materialized yet.

State officials are still in the early stages of understanding how serious this situation is.

Industry executives are focused on their own bottom lines, not regional fuel security.

Nobody is taking ownership of the problem at the scale needed to solve it.

If you live in Arizona or anywhere in the Southwest, here’s what you need to monitor closely and how you can plan ahead.

These are practical steps, not panic moves.

First, track local gas prices daily using multiple sources.

Use apps like GasBuddy, AAA’s fuel price tracker, and even Google Maps, which now shows gas prices at nearby stations.

When you notice sudden jumps of more than 10 cents in a single day, that’s a signal that supply is tightening.

Fill up when prices are stable rather than waiting.

A $5 difference per tank adds up to $60 per month if you fill up weekly.

Over a year, that amounts to $700.

Second, watch for station outages and delivery patterns.

If multiple stations in your area start running out of premium grades or diesel, that’s an early warning sign.

Shortages often hit premium grades first because they’re lower volume, and refineries prioritize regular unleaded production.

If you see that pattern developing, don’t wait for regular unleaded shortages to follow; fill your tank even if you’re not empty yet.

Having a full tank gives you options if shortages spread.

Pay attention to which stations consistently have fuel and which run dry repeatedly.

Build a mental map of reliable stations near your home and workplace.

If one station runs out, you’ll know where to go next without wasting time and fuel driving around searching.

Third, follow state energy announcements from official sources.

Arizona’s Department of Transportation, the Governor’s Office, and the Arizona Corporation Commission will issue alerts if supply disruptions reach critical levels.

Sign up for emergency notifications if your county offers them through text or email; knowing about a potential shortage 24 hours early gives you time to fill up before panic buying empties the stations.

Fourth, consider fuel efficiency changes in your daily routine starting now.

If you’ve been thinking about consolidating trips or carpooling, start doing it immediately.

Combining your grocery shopping with other errands saves fuel, and carpooling to work does too.

Small changes in driving habits can reduce your fuel consumption by 10% to 15% without major lifestyle changes.

Check your tire pressure regularly; underinflated tires reduce fuel efficiency measurably.

Remove unnecessary weight from your vehicle—every 100 pounds of extra cargo reduces fuel economy.

Slow down on highways; driving 75 mph instead of 65 mph significantly increases fuel consumption.

These sound like minor adjustments, but they add up.

A vehicle that gets 25 mpg can easily improve to 27 or 28 mpg with better habits.

That difference matters when you’re trying to stretch your fuel budget.

For businesses that operate vehicle fleets, now is the time to evaluate routes and optimize logistics aggressively.

Route planning software can cut fuel use by 10% to 20% if implemented properly.

Consider shifting delivery schedules to off-peak hours when traffic is lighter; stop-and-go traffic burns more fuel than steady highway driving.

Every gallon saved directly improves your bottom line when prices spike.

Fifth, understand what you can’t control and don’t waste energy worrying about it.

This is not financial advice, but you should know that fuel prices are driven by forces far beyond any individual’s reach.

Refinery closures, pipeline shutdowns, and regulatory decisions happen at corporate and government levels.

You can’t change those outcomes by complaining or posting on social media.

What you can control is your own preparedness and response.

Keep your tank above half full as a general rule; that habit gives you flexibility during supply disruptions.

Budget for higher fuel costs in your monthly planning.

If you’re spending $200 per month on gas now, plan for $260 to $300 per month over the next year.

Adjust other spending categories to accommodate that increase.

Plan alternative transportation if possible.

Can you bike to work one day per week?

Can you take public transit occasionally?

Even small reductions in fuel dependence help.

Sixth, stay informed about pipeline and refinery news in real time.

If another California refinery announces closure or if new pipeline projects get approved, those developments will directly impact Arizona prices within days.

Follow credible news sources focused on energy markets.

Subscribe to industry newsletters if you’re willing to read detailed analysis.

The American Automobile Association publishes weekly fuel market updates, and the Energy Information Administration releases data on refinery operations and fuel stocks every week.

Knowledge gives you a head start before general news media picks up the story.

Seventh, and this is critical: do not panic buy or hoard fuel.

Panic buying creates artificial shortages and exacerbates the situation for everyone.

Fill up when you legitimately need fuel, not because you’re afraid.

Hoarding fuel in containers at home is dangerous and illegal in many jurisdictions.

Gasoline vapors are explosive, and improper storage creates fire risks.

One house fire caused by stored gasoline can destroy your home and endanger your family.

It’s not worth it to take that risk.

Stay rational and think about the community impact of your actions.

Finally, if you have flexibility in your life decisions, consider them now.

If you’re thinking about buying a more fuel-efficient vehicle, this might be the time to do it.

If you’re considering a job change that reduces your commute, factor fuel costs into that decision.

If you’re planning a move, think about proximity to work and services.

These are big decisions that shouldn’t be made solely based on fuel prices, but energy costs are now a permanent consideration in Southwest life planning.

Here’s what you need to remember from everything we just covered: California just lost 284,000 barrels per day of refining capacity, with more closures coming in April.

The San Pablo Bay pipeline that carried 100,000 barrels of crude daily shut down permanently on December 15th.

Arizona relies on California surplus fuel that no longer exists.

Prices are spiking across Phoenix, Tucson, and Flagstaff, and shortages are spreading across the Southwest.

The next six months will determine whether this becomes a manageable disruption or a full-blown regional energy crisis that reshapes the economy.

The three scenarios we discussed show the range of possibilities: the best case requires coordinated action that isn’t happening yet, the base case means permanently higher prices and intermittent shortages, and the worst case involves rationing and economic contraction.

Right now, we’re heading toward the middle scenario unless something changes quickly.

News

😱 Banning Gas Cars While Telling EV Owners Not to Charge: California’s Energy Crisis Explained! 😱 – HTT

California Governor Bans Gas Cars — Then Tells EV Owners Not to Charge Last September, California issued an urgent alert:…

😱 The Power of Love: George Moran’s Emotional Tribute to Tatiana Schlossberg at Her Heartfelt Funeral 😱 – HTT

😱 The Power of Love: George Moran’s Emotional Tribute to Tatiana Schlossberg at Her Heartfelt Funeral 😱 “I wasn’t ready….

😱 The Night Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Kent Benson Collided: A Punch That Changed Basketball Forever! 😱 – HTT

😱 The Night Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Kent Benson Collided: A Punch That Changed Basketball Forever! 😱 The tale of Kareem…

😱 Bob McAdoo Breaks His Silence: The Shocking Truth Behind the NBA’s Biggest Scandal! 😱 – HTT

😱 Bob McAdoo Breaks His Silence: The Shocking Truth Behind the NBA’s Biggest Scandal! 😱 Bob McAdoo has finally broken…

😱 Tatiana Kennedy Schlossberg’s $7.2 Million Decision: A Deep Dive into Love, Legacy, and the Meaning of Home 😱 – HTT

😱 Tatiana Kennedy Schlossberg’s $7.2 Million Decision: A Deep Dive into Love, Legacy, and the Meaning of Home 😱 Tatiana…

😱 Tatiana Schlossberg’s Funeral: A Devastating Day for the Kennedys Filled with Tears and Heartfelt Moments! 😱 – HTT

Tatiana Schlossberg’s Tearful Funeral: How the Kennedy Family Said Final Goodbye The images from Tatiana Schlossberg’s funeral may have flickered…

End of content

No more pages to load