1 MIN AGO: Northern California Earthquake Reveals Hidden Mega-Fault — “The Next San Andreas!”

One minute ago, the ground beneath Northern California tore open with a force that caught even seismologists off guard.

A magnitude 4.7 earthquake ripped through Lawson County, 9 miles northwest of Susanville at precisely 4:41 p.m. on a quiet Sunday afternoon.

The tremor struck at a depth of just 3.3 miles.

Shallow enough that families eating dinner felt their homes lurch sideways.

Grocery aisles at the local Walmart collapsed into twisted metal and scattered produce.

But this earthquake is not what it seems.

And the fault that caused it is hiding something far more dangerous than most people realize.

What is the Walker Lane?

And why are scientists calling it the next San Andreas?

Why did this earthquake happen so far from California’s famous fault lines?

And what does a swarm of 150 earthquakes in San Ramon have to do with a remote valley near the Nevada border?

The earthquake registered initially as magnitude 5.0 before seismologists revised it downward to 4.7.

The United States Geological Survey confirmed the epicenter at 40.54° north latitude, 120.69° west longitude, approximately 9 miles north-northwest of Susanville.

The depth measurement of 5.4 km places this rupture in the shallow crust where seismic energy transfers directly to the surface with brutal efficiency.

Shake Alert, the USGS early warning system, fired off notifications to smartphones seconds before the shaking arrived.

Those precious few seconds allowed some residents to drop, cover, and hold on before the jolt hit.

The modified Mercalli intensity scale recorded level five shaking near the epicenter.

Windows rattled, dishes fell, and light fixtures swayed violently.

Reports flooded in from as far south as Sacramento, 200 miles away, and east into Reno, Nevada.

The felt radius exceeded 100 miles in multiple directions.

Population centers like Chico and Redding experienced light tremors that lasted several seconds.

For a 4.7 magnitude event, the geographic reach was unusually broad.

But this was only the first warning.

Shallow earthquakes behave differently than their deep cousins.

When an earthquake ruptures at depths below 10 km, much of its energy dissipates through the rock layers before reaching the surface.

But at 3.3 miles down, there is almost no buffer.

The seismic waves slam directly into buildings, roads, and infrastructure with minimal attenuation.

This is why a magnitude 4.7 felt like magnitude 5.5 to residents directly above the rupture.

The shallow focus amplified the ground motion, turning a moderate earthquake into a violent, jarring experience.

Inside the Susanville Walmart, surveillance footage captured the moment shelves began swaying.

Canned goods tumbled into the aisles.

Glass jars shattered.

Employees and customers froze for a heartbeat before rushing toward exits.

The store remained closed for safety inspections.

Throughout Susanville and nearby Johnstonville, residents described a low rumbling that built into a sharp jolt.

Furniture shifted.

Pictures fell from walls.

The smell of dust filled the air as homes settled back into place.

What came next shocked even the scientists.

Most people hearing about a Northern California earthquake assume one thing: the San Andreas fault.

But this earthquake occurred nowhere near it.

The San Andreas fault runs along California’s western edge from the Gulf of California north to Cape Mendocino.

Susanville sits nearly 200 miles northeast of the fault’s nearest trace.

The tectonic forces at work here belong to an entirely different system, one that most Californians have never heard of.

This disconnect creates dangerous complacency.

Residents in remote Northern California often believe they are safe from major seismic threats because they live far from the San Andreas.

That belief is wrong.

The real danger lies beneath their feet in a complex, fragmented network of faults that scientists are only beginning to understand.

And the signs were already spreading.

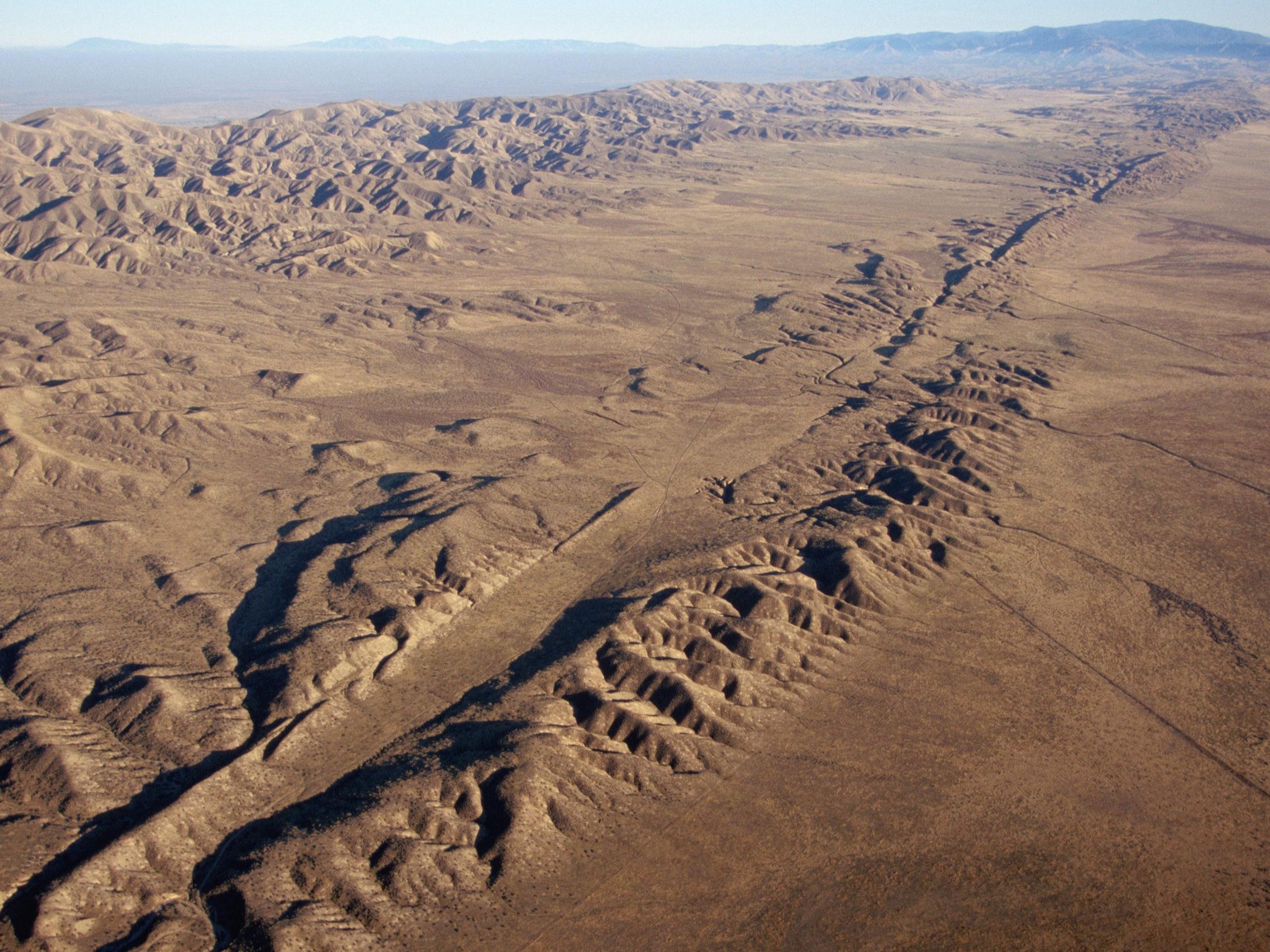

The Walker Lane is not a single fault.

It is a 700-mile long belt of deformation stretching from southern California north through Nevada and into northeastern California.

This zone accommodates roughly 15 to 25% of the motion between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates.

The remaining 75 to 85% occurs along the San Andreas fault system.

But unlike the San Andreas, which is relatively continuous and well-mapped, the Walker Lane is discontinuous, complex, and evolving.

Scientists from the University of Nevada Reno and the USGS have spent decades trying to understand the Walker Lane’s northern terminus.

South of Pyramid Lake, the system’s boundaries are clear, but north of Reno, the faults become fragmented and harder to trace.

Susanville has emerged as a critical location in this puzzle.

Geologists believe the Walker Lane may propagate northward through this region, eventually ripping through northeastern California and southwest Oregon to reach the Pacific Ocean.

If that happens, millions of years from now, Nevada could become the new West Coast.

GPS measurements show the Walker Lane accommodates roughly 12 mm per year of right lateral motion.

That may sound small, but over geological time, it adds up.

The system is geologically young, less than a few million years old in its northern sections.

It is actively forming right now.

Every earthquake, every shift is part of a continent tearing itself apart.

But the ground had one more secret.

The Honey Lake fault zone runs directly through the Susanville area.

This fault system forms part of the boundary between the Sierra Nevada block and the basin and range province.

The faults are vertical with right lateral oblique displacement, meaning they slide sideways while also lifting one side relative to the other.

Geological studies document at least 800 m of vertical displacement and more than 10 km of lateral slip since faulting began in the mid-Miocene roughly 15 million years ago.

Evidence of recent activity is everywhere for those who know where to look.

The 12,000-year-old shoreline of an ancient lake shows clear offsets where the fault ruptured after the lake receded.

Trenching studies reveal multiple prehistoric earthquakes preserved in the sediment layers.

The most recent significant event occurred in 1950 when the Fort Sage earthquake, estimated at magnitude 5.6, ruptured the surface and caused moderate damage across the region.

The Honey Lake fault zone is not dormant.

It is active, capable, and due.

Scientists estimate these faults can generate earthquakes up to magnitude 7.0 or higher.

A magnitude 7 earthquake in this sparsely populated region would still cause catastrophic damage.

But if it occurred during peak tourist season in nearby Lassen Volcanic National Park, or if it triggered secondary hazards like landslides or dam failures, the death toll could climb rapidly.

This was only the beginning.

Beyond the Honey Lake fault, Lassen County hosts a spiderweb of smaller faults.

The Fort Sage fault extends southeast from the Honey Lake system.

The Mohawk Valley fault zone runs parallel to the northwest.

Each fault is capable of producing damaging earthquakes.

Together, they form an interconnected network where stress on one fault can transfer to another, triggering cascading failures.

The 1950 Fort Sage earthquake demonstrated this potential.

The rupture extended for several miles and caused surface offsets visible for decades afterward.

Chimneys collapsed in nearby towns.

Roads buckled.

Wells went dry or turned turbid as groundwater systems shifted.

Modern building codes did not exist in 1950.

If a similar earthquake struck today, the damage would be different, but no less severe.

Mobile homes common in rural California perform poorly in earthquakes.

Water and power infrastructure remains vulnerable.

The region’s geology amplifies seismic risk.

The valleys are filled with unconsolidated sediments that shake violently during earthquakes.

These basin effects can double or triple ground motion compared to bedrock sites.

Susanville sits in just such a valley, surrounded by mountains on three sides.

During an earthquake, seismic waves bounce off the valley walls, prolonging the shaking and increasing the potential for structural damage.

Every data point now points to a system under strain.

Lassen Volcanic National Park sits less than 50 miles west of Susanville.

Lassen Peak last erupted from 1914 to 1917 in a series of explosions that sent ash clouds 30,000 feet into the atmosphere.

The region remains volcanically active with fumaroles, boiling mud pots, and hot springs.

The USGS monitors the area continuously with seismometers, GPS stations, and gas sensors.

Any increase in earthquake activity near Lassen raises the question: is this tectonic faulting or is magma moving beneath the surface?

The relationship between volcanism and faulting is complex.

Magma rising through the crust can trigger earthquakes.

Conversely, earthquakes can fracture the rock and create pathways for magma to ascend.

The Lassen volcanic center sits at the southern end of the Cascade Range, fed by subduction of the Gorda plate beneath North America.

Desiccated magma chambers exist at shallow depths ready to erupt if the right conditions develop.

Scientists from the California Volcano Observatory emphasize that the Susanville earthquake shows no evidence of volcanic origin.

The depth, mechanism, and location are consistent with tectonic faulting, but they cannot rule out the possibility that continued seismic activity could disturb the volcanic system.

The dual threat of earthquakes and potential eruptions makes this region one of the most geologically hazardous in California.

What the experts could not predict is what happened next.

Sarah Jensen woke to the sound of glass shattering.

She lived in a two-story home on the outskirts of Susanville, surrounded by pine trees and open fields.

The earthquake hit without warning, a violent sideways lurch that threw her out of bed.

Her first thought was for her children sleeping in the next room.

She stumbled down the hallway as the floor bucked beneath her feet.

The walls groaned.

Dust rained from the ceiling.

“It felt like the house was being picked up and shaken,” she said.

By the time she reached her children, the shaking had stopped, but the fear remained.

Outside, neighbors gathered in the street, some still in pajamas.

Car alarms blared.

Dogs barked frantically.

The smell of earth and broken wood hung in the air.

Sarah’s house had survived with only minor damage.

Cracks in the drywall, a broken window, toppled furniture.

Others were not so lucky.

On the outskirts of town, older mobile homes had shifted on their foundations.

Water lines had ruptured, flooding yards.

The earthquake was over, but the recovery was just beginning.

But this was not an isolated event.

200 miles southwest, another fault system was stirring.

The San Ramon area in the Bay Area’s East Bay had experienced more than 150 earthquakes since early November.

The swarms continued into December with magnitude 4.0 earthquakes rattling the city multiple times.

Residents reported feeling tremors at all hours during dinner, in the middle of the night, while showering.

The constant activity frayed nerves and raised questions.

The San Ramon swarms occur on the Calaveras fault, part of the San Andreas fault system.

But scientists noted an unusual pattern.

The timing of the Susanville earthquake combined with ongoing activity in San Ramon suggested that stress was redistributing across Northern California.

GPS data showed subtle ground deformation.

Seismic energy was building in places that had been quiet for decades.

Whether these events were connected or coincidental remained unclear.

The USGS emphasized that earthquake swarms like those in San Ramon are normal and do not necessarily precede a larger event, but they acknowledged uncertainty.

Earthquakes are fundamentally unpredictable.

The best science can do is calculate probabilities and monitor for warning signs.

The San Ramon swarms, the Susanville earthquake, and elevated activity elsewhere in California could be unrelated, or they could be precursors to something far worse.

Infrastructure across the region remains dangerously vulnerable.

Power transmission lines cross multiple fault zones.

A major rupture could sever connections between Northern California and the rest of the state grid.

Water systems rely on aging pipelines that were installed decades before modern seismic standards existed.

Emergency response in rural areas like Lassen County depends on a handful of understaffed fire departments and volunteer search and rescue teams.

If roads become impassable due to landslides or bridge failures, entire communities could be cut off for days or weeks.

The National Grid Corporation has identified critical transmission towers in the region that may not withstand strong shaking.

Replacement or retrofitting requires funding that has not materialized.

Hospitals in Susanville and nearby towns have emergency generators, but fuel supplies are limited.

Communications infrastructure relies on cell towers that have backup power for only 24 to 48 hours.

Once those batteries drain, contact with the outside world ends.

Water is the most critical concern.

The region depends on groundwater wells and small reservoirs.

Earthquakes can disrupt aquifers, causing wells to go dry or become contaminated.

Surface reservoirs face dam failure risks.

The Frenchman Lake Dam northwest of Susanville impounds a significant volume of water.

A magnitude 7 earthquake could compromise the dam, sending a wall of water downstream toward populated areas.

Emergency planners have mapped inundation zones, but evacuation plans remain theoretical, and the warnings kept coming.

Scientists disagree on fundamental questions about the Walker Lane and the faults near Susanville.

Some researchers argue that the Honey Lake fault zone is capable of magnitude 7.5 earthquakes based on fault length and slip rate.

Others contend that the faults are too segmented and that magnitude 7.0 is a more realistic upper bound.

Both scenarios are catastrophic, but the difference matters for building codes and emergency preparedness.

The Walker Lane’s northern route remains speculative.

Will it propagate through Susanville as some models suggest, or will it follow a different path through the Modoc Plateau?

The answer determines which communities face the greatest long-term risk.

Geologists have identified potential fault traces using LIDAR and satellite imagery, but field verification is incomplete.

Many of these faults lie beneath thick vegetation or agricultural land, making surface mapping difficult.

Aftershock forecasts are another point of contention.

The USGS issued a standard aftershock advisory following the Susanville earthquake, stating that aftershocks are likely in the coming days and weeks, but the exact probability of a larger earthquake triggering depends on models that are still being refined.

Some seismologists believe the risk is low.

Others point to historical cases where a moderate earthquake preceded a much larger event within months.

The debate extends to volcanic hazards.

While most scientists agree that the Susanville earthquake was purely tectonic, a minority argue that increased faulting could destabilize magma chambers beneath Lassen Peak.

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was preceded by weeks of earthquakes.

Could a similar pattern unfold at Lassen?

Monitoring data shows no signs of magma movement, but volcanic systems can change rapidly.

The lack of unrest today does not guarantee safety tomorrow.

Right now, scientists know this much.

The Susanville earthquake occurred on a fault system that is part of the Walker Lane, a 700-mile long zone accommodating up to 25% of Pacific North American plate motion.

The earthquake struck at a shallow depth, amplifying its felt intensity across a wide area.

The Honey Lake fault zone and surrounding faults are active and capable of generating magnitude 7 earthquakes or larger.

Infrastructure in the region is poorly prepared for major seismic events.

Aftershocks are likely, though their magnitude and timing cannot be predicted.

What remains unknown is more troubling.

Scientists do not know when the next significant earthquake will strike.

They do not know if the Walker Lane will continue propagating northward or if it will stall.

They do not know whether the San Ramon swarms and the Susanville earthquake are related or independent.

They do not know if continued seismic activity will disturb the volcanic systems beneath Lassen Peak.

They do not know how many people live in structures that will collapse during a magnitude 7 earthquake.

And they do not know how much time is left before the ground opens.

News

😱 California’s Food Industry COLLAPSES After Del Monte’s Shocking Bankruptcy Announcement 😱 – HTT

California’s Food Industry COLLAPSES After Del Monte’s Shocking Bankruptcy Announcement Del Monte Foods, a name synonymous with canned fruits and…

😱 Macaulay Culkin’s Heartbreaking Goodbye to Catherine O’Hara – You Won’t Believe What He Said! 😱 – HTT

😱 Macaulay Culkin’s Heartbreaking Goodbye to Catherine O’Hara – You Won’t Believe What He Said! 😱 Catherine O’Hara, the celebrated…

😱 California Coast Is Breaking Apart Right Now – Experts Say There’s No Stopping It 😱 – HTT

😱 California Coast Is Breaking Apart Right Now – Experts Say There’s No Stopping It 😱 Along California’s coast, scenes…

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Mount Maunganui MASSIVE Landslide Destorys City – “It Happened So Fast” 😱 – HTT

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Mount Maunganui MASSIVE Landslide Destorys City – “It Happened So Fast” 😱 On the morning of…

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Scientists Discover HUGE FRACTURES Underneath Niagara Falls – It’s Worse Than We Thought 😱 – HTT

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Scientists Discover HUGE FRACTURES Underneath Niagara Falls – It’s Worse Than We Thought 😱 January 2025…

😱 LOS ANGELES UNDERWATER – Scientists Warn This Flood Was “Worse Than Expected” 😱 – HTT

😱 LOS ANGELES UNDERWATER – Scientists Warn This Flood Was “Worse Than Expected” 😱 Los Angeles, long known for its…

End of content

No more pages to load