😱 The Shocking Truth Behind California’s Crumbling Coastal Highway – You Won’t Believe Who’s Responsible! 😱

California’s Pacific Coast Highway is renowned for its breathtaking views, winding along cliffs and hugging the ocean’s edge.

Yet beneath this iconic roadway, a hidden and escalating danger threatens not only the road itself but the communities it serves.

The ground supporting the highway is not stable; it is slowly sliding toward the ocean in a process geologists call an earth flow.

Unlike dramatic, sudden disasters, this movement is gradual and almost imperceptible, inching forward year after year.

At Last Chance Grade, a notorious section of the highway, this creeping instability has persisted for over a century.

Engineers have fought a losing battle, building retaining walls and reinforcing foundations, only to watch cracks reappear and the earth continue its slow slide.

The sliding surface lies hundreds of feet underground, allowing the road to appear intact even as massive volumes of earth shift beneath it.

This slow-motion hazard presents a paradox: the road must flex and bend to survive, but every structure has its limits.

Over time, steel fatigues and concrete fractures, increasing the risk of sudden failure.

This creeping earth flow is not just a theoretical risk; it has already caused catastrophic landslides that have shut down the highway for months at a time.

In 2011, a major slide near Big Sur forced the replacement of a highway section with a bridge and protective rock shed, a temporary fix at best.

In 2017, the Mud Creek landslide buried nearly a third of a mile of road under 40 feet of debris, moving enough earth to fill hundreds of Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The coastline shifted outward, creating new land where once there was ocean.

More recently, storms in 2023 triggered further landslides, closing nearly 40 miles of highway and forcing the abandonment of some sections altogether.

These events follow a grim pattern: heavy rains saturate unstable slopes, the ground gives way, and communities are cut off.

Repairs restore access temporarily, but the risk quietly returns.

For residents north of Last Chance Grade, the highway is far more than a scenic route—it is a lifeline.

Schools, hospitals, grocery stores, and workplaces all depend on this single road.

When it closes, daily life slows and fractures.

Dairy farms in Del Norte County, for example, rely on the highway for shipping products statewide.

When the road shuts down, trucks must take detours hundreds of miles long, inflating costs and threatening livelihoods.

Emergency services face even graver challenges: during past closures, medical workers have had to carry critical supplies by hand across unstable terrain to reach patients.

The alternatives are bleak.

The only other routes require an eight-hour drive through mountainous terrain in Oregon and inland California.

On a map, the landslide zones may seem small, but in reality, they isolate entire communities.

As closures become more frequent, tourism declines, businesses struggle, property values drop, and younger families consider leaving.

The instability of the road is reshaping not just travel but the future of the region itself.

In response to these mounting challenges, a bold proposal has emerged: a tunnel roughly three miles long, drilled deep beneath the sliding earth.

This tunnel promises a permanent, stable connection unaffected by surface movements.

It would eliminate the need for constant repairs and seasonal closures.

But the project comes with an enormous price tag—around $2 billion—and significant risks.

The tunnel does not halt the earth flow; it simply bypasses it.

Above, the land will continue to shift unpredictably.

Moreover, the region lies near the Cascadia subduction zone, capable of triggering earthquakes far stronger than those historically experienced in California.

No structure, no matter how well engineered, can guarantee permanence in such a volatile environment.

The $2 billion investment buys time, not certainty.

Meanwhile, as attention focuses on the tunnel, the present situation grows more precarious.

The existing highway continues to bear the burden of shifting ground.

Sensors reveal that during heavy rain years, the road can move several inches per week.

Each movement increases repair costs and risk, even when no immediate alarms sound.

Closures become more frequent, detours longer, and daily life more disrupted.

A troubling paradox emerges: as hope for a tunnel solution grows, residents tolerate greater risk on the current road.

The highway remains open not because it is safe, but because there is no alternative.

Trust begins to erode—not in the road itself, but in the system responsible for protecting the people who depend on it.

Looking ahead, no perfect solution exists.

Continuing to patch the road accepts rising danger and costs, with each rainy season a gamble.

The tunnel offers a potential lifeline but concentrates the community’s future into a single infrastructure gamble.

If it fails, there is no backup.

There is a third, seldom-discussed option: planned retreat.

Accepting that some places may no longer be sustainable means relocating services, creating new economic pathways, and helping residents move if they choose.

This choice carries deep cultural, economic, and psychological costs that are difficult to quantify.

Complicating matters further is the reality that decisions are made far from the shifting ground—by officials distant from daily life on the coast.

Last Chance Grade has become more than a highway; it is a mirror reflecting how society confronts the limits of control over natural forces.

There is no sudden disaster here, only a slow, persistent process that forces difficult questions: Should California gamble billions on a tunnel that may only buy time?

Or is it time to embrace adaptation rather than resistance?

For now, the ground continues to move, the road stays open, and an entire community waits in a fragile balance between hope and uncertainty.

News

😱 California’s Food Industry COLLAPSES After Del Monte’s Shocking Bankruptcy Announcement 😱 – HTT

California’s Food Industry COLLAPSES After Del Monte’s Shocking Bankruptcy Announcement Del Monte Foods, a name synonymous with canned fruits and…

😱 Macaulay Culkin’s Heartbreaking Goodbye to Catherine O’Hara – You Won’t Believe What He Said! 😱 – HTT

😱 Macaulay Culkin’s Heartbreaking Goodbye to Catherine O’Hara – You Won’t Believe What He Said! 😱 Catherine O’Hara, the celebrated…

😱 California Coast Is Breaking Apart Right Now – Experts Say There’s No Stopping It 😱 – HTT

😱 California Coast Is Breaking Apart Right Now – Experts Say There’s No Stopping It 😱 Along California’s coast, scenes…

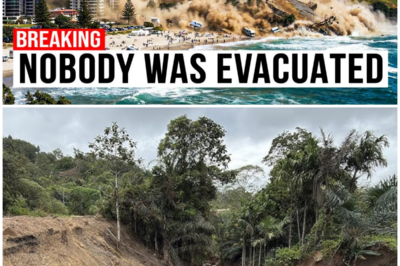

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Mount Maunganui MASSIVE Landslide Destorys City – “It Happened So Fast” 😱 – HTT

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Mount Maunganui MASSIVE Landslide Destorys City – “It Happened So Fast” 😱 On the morning of…

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Scientists Discover HUGE FRACTURES Underneath Niagara Falls – It’s Worse Than We Thought 😱 – HTT

😱 1 MINUTE AGO: Scientists Discover HUGE FRACTURES Underneath Niagara Falls – It’s Worse Than We Thought 😱 January 2025…

😱 LOS ANGELES UNDERWATER – Scientists Warn This Flood Was “Worse Than Expected” 😱 – HTT

😱 LOS ANGELES UNDERWATER – Scientists Warn This Flood Was “Worse Than Expected” 😱 Los Angeles, long known for its…

End of content

No more pages to load