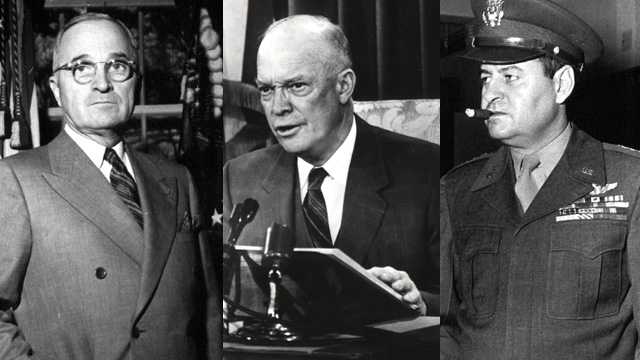

By the summer of 1945, Dwight D. Eisenhower was no stranger to devastation.

He had commanded the largest amphibious invasion in human history.

He had walked through liberated concentration camps where the stench of death clung to the walls like a second skin.

He had ordered men into battles he knew many would not survive.

War, to Eisenhower, was not abstract.

It was personal, calculated, and brutal—but it still followed rules.

When Truman informed him of the atomic bomb, those rules collapsed.

The setting was restrained, almost deceptively ordinary.

Truman spoke of the weapon as a technological breakthrough, the culmination of years of secret research and staggering expense.

He described its power in controlled terms, but even the most cautious language could not disguise the implication: a single bomb capable of erasing a city.

Eisenhower listened without interrupting.

Those who later recounted the moment described his expression as tight, his posture stiff.

This was not awe.

It was alarm.

When Eisenhower finally responded, his words did not match the triumphal mood circulating among many policymakers.

He told Truman he believed Japan was already militarily defeated.

Its navy shattered, its air force crippled, its cities reduced to ruins by conventional bombing.

Eisenhower argued that using such a weapon was unnecessary from a strategic standpoint.

But his objection went deeper than tactics.

He warned that deploying the bomb would shock global opinion and permanently damage America’s moral standing.

This was not the protest of a pacifist.

It was the warning of a man who understood how power reshapes the world long after the shooting stops.

Eisenhower later described feeling a “depression” settle over him during that conversation.

The bomb, he sensed, was not simply another step in the evolution of warfare.

It was a rupture so extreme it would redefine what war meant.

Until then, destruction had limits—cities could be rebuilt, populations could recover, history could move forward.

The atomic bomb threatened annihilation without recovery, death without distinction, victory without honor.

Once used, it could never be unseen.

Truman, for his part, was unmoved.

The pressure on him was immense.

Military planners estimated catastrophic casualties if the war dragged on.

Scientists assured him the bomb would work.

Advisors framed it as a necessary horror to end a greater one.

Eisenhower’s objections were acknowledged politely and then absorbed into the vast machinery of decision-making, where moral doubt was outweighed by urgency and momentum.

The train was already moving, and no single voice—no matter how respected—could stop it.

What makes Eisenhower’s reaction so haunting is how consistent it remained throughout his life.

Years after the war, he continued to express unease about the atomic bomb’s use.

He spoke of it not as a triumph but as a tragedy layered on top of an already tragic war.

Unlike others who justified the decision with certainty, Eisenhower’s reflections were marked by restraint and discomfort.

He did not deny the bomb ended the war.

He questioned whether ending it that way had opened a door humanity was unprepared to walk through.

The weeks that followed Truman’s revelation would vindicate Eisenhower’s fears in the most horrifying way imaginable.

Hiroshima disappeared in a flash brighter than the sun.

Shadows of human beings were burned into stone.

Nagasaki followed, sealing the message that the world had entered a new era.

Eisenhower, watching events unfold, reportedly felt no sense of victory.

Only confirmation.

The weapon had done exactly what he feared it would do—not just to Japan, but to the future.

As the Cold War emerged from the ruins of World War II, Eisenhower’s early misgivings took on prophetic weight.

Nations raced to build bigger bombs, faster missiles, deeper bunkers.

Fear became institutionalized.

Entire generations grew up under the constant threat of instant annihilation.

When Eisenhower later warned Americans about the military-industrial complex, his words carried the memory of that first atomic revelation.

He had seen how innovation, once fused with fear and profit, becomes almost impossible to restrain.

Public history often flattens this moment into a footnote, portraying Eisenhower as a bystander to a decision already made.

But the truth is more uncomfortable.

His reaction reveals that doubt existed at the very top, that the moral consequences were understood even before the bomb fell.

This complicates the narrative of inevitability.

It suggests that history did not march forward blindly, but consciously, with full awareness of the abyss opening ahead.

Eisenhower never claimed moral superiority.

He did not grandstand or resign in protest.

He carried his objections quietly, the way soldiers often carry the heaviest burdens.

But silence does not equal consent.

His response to Truman stands as a rare moment when power paused, if only briefly, to look itself in the mirror.

And what it saw was not glory, but a future haunted by its own ingenuity.

In the end, what Eisenhower said matters because it exposes a truth we prefer to ignore: the atomic age was not born from ignorance, but from choice.

A choice made under pressure, defended with logic, and shadowed by fear.

Eisenhower understood that once the bomb was used, the world would never be the same.

He was right.

And that quiet conversation, tucked away behind layers of official history, remains one of the most chilling reminders that sometimes the most important warnings are the ones we hear—and choose not to follow.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load