Saqqara has never been a quiet place in the historical imagination.

It is where stone architecture first rose monumentally from the earth, where dynasties experimented with eternity, and where death became a science.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser still dominates the plateau, announcing Egypt’s first great leap into permanence.

For centuries, Saqqara has been excavated, cataloged, and measured until many believed it had little left to offer.

Maps were full.

Shafts were logged.

Chambers were assigned numbers and dates.

The assumption was simple: Saqqara was known.

That assumption began to crack not with a shovel, but with data.

In recent years, archaeologists revisiting old survey records noticed something subtle but persistent.

Digital mapping and modern subsurface scanning did not fully agree with earlier documentation.

In places marked “cleared,” density readings suggested inconsistencies beneath the rock.

At first, these were dismissed as noise—equipment interference, natural fractures, harmless anomalies.

But when repeated scans using different instruments produced the same results, confidence eroded.

The data showed boundaries where there should have been none.

What made the anomaly more disturbing was its location.

It did not align with any known tomb complex.

It was not connected to storage chambers, catacombs, or service corridors.

There were no entrances recorded in ancient texts or modern excavation logs.

If the scans were correct, then something had been missed—or hidden.

The team proposed a limited investigation, framed carefully as confirmation rather than discovery.

Expectations remained low.

Saqqara has a way of humbling ambition.

Excavation resumed slowly, removing only what was necessary while monitoring subsurface changes in real time.

Early layers offered nothing unusual.

Pottery fragments, wood debris, disturbed soil—all consistent with Roman-era activity known at the site.

Confidence grew that the anomaly would resolve into a collapsed niche or abandoned cut.

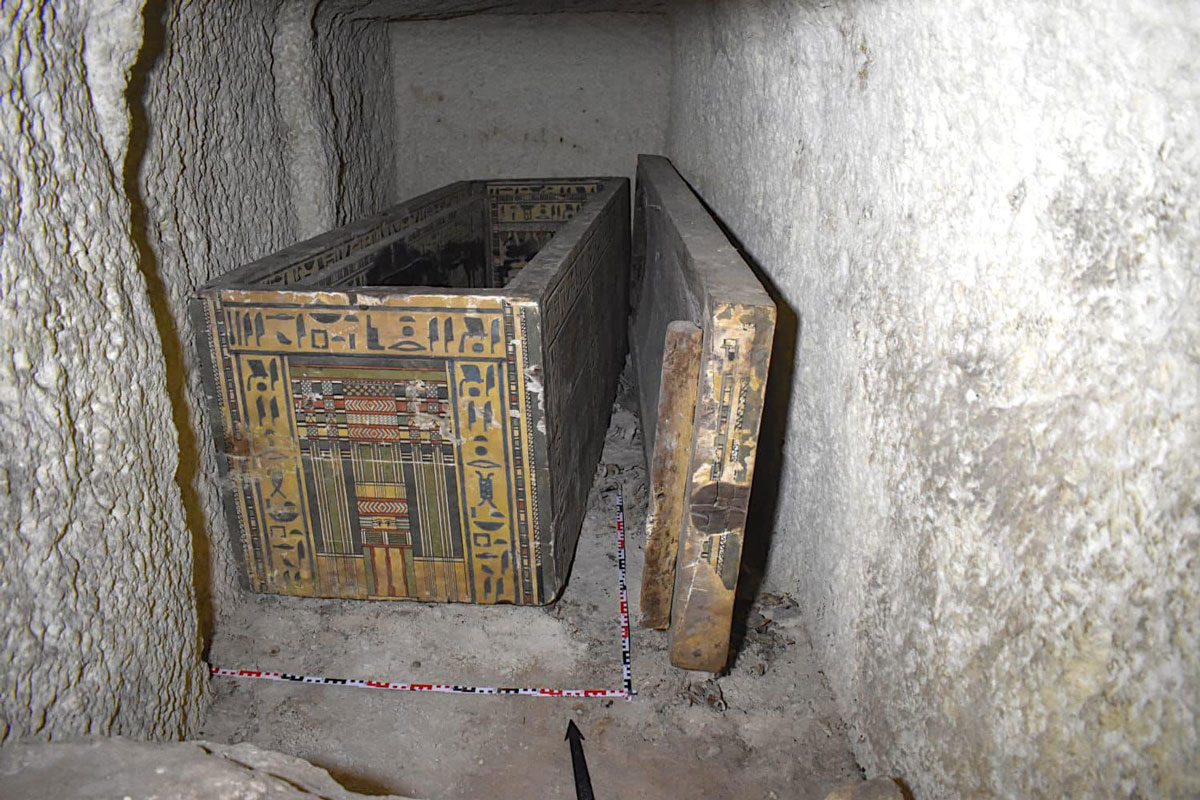

Then the shaft ended.

Not in a chamber.

Not in a niche.

Not even in a visible seal.

It ended at a smooth vertical wall.

This alone was wrong.

Burial shafts do not terminate blindly.

Even sealed chambers announce themselves—with inscriptions, symbols, protective texts.

Egyptian death culture demands explanation.

This wall offered none.

No name.

No warning.

No sign that a burial lay beyond.

Just stone, placed deliberately.

The team stopped immediately.

Tools were lowered.

The wall was documented from every angle.

What they saw deepened the unease.

The tool marks were uneven, rushed, then partially smoothed.

Not finished for reverence, but disguised.

This was not meant to be noticed.

It was meant to disappear into the shaft as if it had always been there.

Ground scans were reviewed again.

This time, with the wall as context, the results were unambiguous.

There was empty space behind it.

Stable.

Rectangular.

Deliberate.

Not a collapse.

Not erosion.

Then came the detail that shifted the entire interpretation: the wall had been reinforced more than once.

Different binding materials appeared at different depths.

Stone alignment changed subtly.

Someone had returned to this wall.

Reopened it.

Resealed it.

And strengthened it.

That was the moment archaeology crossed into something darker.

This was no abandoned project.

No forgotten tomb.

It was an effort—maintained over time—to keep something inaccessible.

The decision to open the wall was not unanimous.

Archaeologists argued fiercely.

Once breached, the microclimate inside would be destroyed.

Organic material could decay in hours.

But leaving it sealed carried its own risk.

Knowledge deferred too long becomes knowledge lost.

Eventually, the question stopped being whether to open the wall and became how to open it without destroying what lay beyond.

Only hand tools were approved.

No heavy equipment.

No vibration.

Progress was slow, exhausting, and silent.

When the opening was finally large enough, instruments were lowered to test air quality and stability.

Everything held.

A single light was prepared.

When the beam passed through the opening, the debate ended.

Inside was not a tomb.

There were no coffins.

No sarcophagi.

No offerings.

No altars.

The floor was clear.

The walls were bare.

For a moment, confusion reigned.

Then the light shifted.

Human skulls were grouped together in one area of the room, arranged closely, deliberately.

Not scattered.

Not broken by collapse.

Placed.

Long bones were stacked separately—leg bones aligned together, arm bones grouped elsewhere.

Smaller bones formed distinct clusters.

No complete skeletons existed.

No skull matched a spine.

No limbs belonged to a body.

Identity had been dismantled.

This was not looting.

Looting produces chaos.

This room displayed order.

It showed intent.

Worse still, the layering of remains suggested repeated use.

Older bones had been moved to make space for new ones.

The room had functioned over time.

Archaeologists are trained to face death.

Tombs are familiar.

Mummies are routine.

This was different.

This was not burial.

It was a system.

No inscriptions explained the practice.

No names preserved identity.

In Egyptian belief, to lose one’s name is to die a second death.

Here, identity was not merely absent—it was removed.

This contradicted one of the most fundamental assumptions of Egyptian mortuary tradition: that the body must remain whole to survive the afterlife.

The implications were immediate and destabilizing.

If this room existed, then Egyptian death practices were not uniform.

There were circumstances—unknown, undocumented—where bodies were treated in ways never meant for public memory.

This suggests an undocumented stage between death and burial, or an alternative entirely.

A process carried out deliberately, systematically, and then erased.

The sealing of the room reinforces that conclusion.

This was not preserved for future generations.

It was hidden.

Reinforced.

Forgotten on purpose.

Someone decided this practice no longer belonged in Egypt’s story.

Why?

Punishment is one possibility.

Control is another.

Ritual preparation, purification, or something even more unsettling.

What matters is that no known text describes it.

The silence now looks intentional.

Knowledge meant to be used, not remembered.

And that is why this discovery changes history.

Egypt has always presented death as orderly, reverent, and eternal.

Tomb art, inscriptions, and rituals project consistency.

This room exposes a fracture beneath that image.

It suggests that official history was curated even in antiquity—that not all practices were meant to survive in memory.

What was found beneath Saqqara is not just an anomaly.

It is proof that part of Egypt’s relationship with death was hidden, sealed, and nearly lost forever.

The room does not offer answers.

It removes certainties.

It forces historians to accept that the ancient world was not as transparent as its monuments suggest.

Two thousand years ago, someone decided this space should disappear.

They almost succeeded.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load