The Manhattan Project was never designed as a two-bomb gamble.

It was an industrial juggernaut, a continental-scale machine built to keep producing atomic weapons as long as the war demanded them.

Uranium enrichment plants in Oak Ridge, Tennessee ran day and night.

Plutonium reactors at Hanford, Washington continued to breed new cores.

At Los Alamos, New Mexico, scientists and technicians worked methodically, assembling the components of annihilation with growing efficiency.

By August 1945, the system was no longer experimental.

It was operational.

General Leslie Groves, the military commander of the Manhattan Project, had established a clear production schedule.

The third plutonium core was slated to be ready by August 19—just ten days after Nagasaki.

After that, additional cores would follow every three to four days.

The pace was accelerating.

Atomic bombing was on the verge of becoming routine.

This third bomb was not a sketch on a chalkboard or a hopeful projection.

It was being built.

The plutonium core was machined.

The explosive lenses were tested.

The familiar Fat Man casing was assembled.

Once complete, the weapon would be shipped to Tinian Island in the Pacific, where the 509th Composite Group waited with specially modified B-29 bombers.

The crews were trained.

The procedures refined.

From assembly to delivery, the timeline measured days, not weeks.

And the question looming over Washington was simple and terrible: where would it fall?

Earlier that year, a Target Committee had met repeatedly to decide which cities would bear the burden of this new weapon.

The criteria were cold and precise.

The city had to be large enough to demonstrate overwhelming power.

It had to be relatively untouched by conventional bombing so the atomic destruction would be unmistakable.

And it needed military or industrial significance, at least on paper.

The original list included Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, Nagasaki—and Kyoto.

Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital and cultural soul, was initially a prime candidate.

It was spared only because Secretary of War Henry Stimson personally intervened.

He understood that destroying Kyoto would poison any chance of peace, turning the Japanese population irreversibly against the United States.

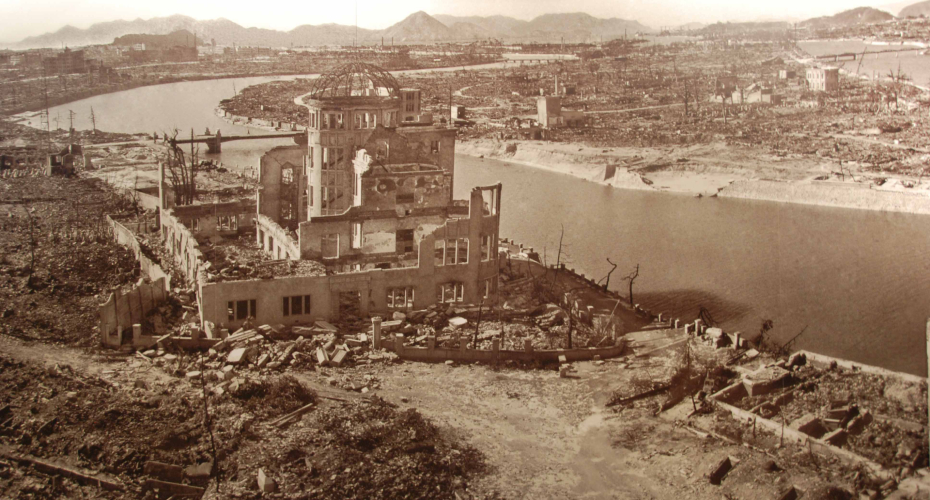

With Kyoto removed, Hiroshima and Nagasaki fell.

After August 9, Kokura and Niigata remained on the list.

But planners were already thinking bigger.

Tokyo began to emerge as the preferred target for the third atomic bomb.

Tokyo was not just another city.

It was the political, administrative, and symbolic heart of Japan.

The emperor’s palace stood at its center.

Every ministry directing the war effort operated there.

An atomic strike on Tokyo would not merely destroy infrastructure; it would shatter the psychological core of the Japanese state.

It would send a message no communiqué ever could: nowhere was safe.

Not even the emperor himself.

This was not an abstract discussion.

On July 25, 1945, the order authorizing atomic strikes was issued.

It granted General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, authority to continue bombing as soon as weapons became available.

No additional presidential approval was required for each strike.

The atomic campaign, once begun, was meant to continue.

Stopping it would require active intervention.

President Harry Truman was struggling to comprehend what he had unleashed.

When reports from Hiroshima arrived, he was shaken.

According to accounts, he told his cabinet that he didn’t want to kill any more children.

Yet every alternative before him carried its own nightmare.

An invasion of Japan—Operation Downfall—was scheduled for November.

Estimates projected hundreds of thousands of American casualties and millions of Japanese deaths.

The battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa had already shown how ferociously Japan would defend its homeland.

And the clock was ticking in more ways than one.

On August 8, the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan, unleashing a massive offensive in Manchuria.

Stalin’s armies crushed Japanese forces with shocking speed.

If the war dragged on, Soviet troops could land on the northern Japanese home islands.

The result might be a divided Japan, occupied like Germany and Korea.

Ending the war quickly was no longer just about saving lives—it was about shaping the postwar world.

While American planners prepared the third bomb, Japan’s government was paralyzed.

Even after Hiroshima.

Even after Nagasaki.

Even after the Soviet invasion.

The Supreme Council for the Direction of the War remained deadlocked.

The peace faction, led by Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō, argued for surrender under one condition: preservation of the emperor.

The military faction demanded far more—no occupation, self-disarmament, Japanese control over war crimes trials.

They refused to yield.

As they argued, the machinery of atomic war kept moving.

It took something unprecedented to break the stalemate.

On August 10, Emperor Hirohito intervened directly, an act that shattered centuries of tradition.

He ordered his government to accept Allied terms, provided the imperial institution was preserved.

But even then, the danger was not over.

On the night of August 14, hardline officers attempted a coup.

They seized parts of the Imperial Palace, murdered the commander of the Imperial Guards, and tried to destroy the emperor’s recorded surrender message.

For hours, Japan teetered on the edge.

Had the coup succeeded, there would have been no surrender broadcast.

The third atomic bomb would have arrived at Tinian Island on schedule.

And the next target—very likely Tokyo—would have been selected.

At noon on August 15, the emperor’s voice crackled over radio receivers across Japan.

For the first time, the people heard him speak.

He announced surrender.

World War II was over.

It was an astonishingly close call.

The plutonium core intended for the third bomb did reach Tinian.

But by the time it arrived, there was no city left to destroy.

Instead, that core was repurposed.

It became the heart of the fourth nuclear detonation—tested at Bikini Atoll in 1946 during Operation Crossroads.

The bomb meant for Tokyo vaporized empty warships instead.

Yet the system never stopped.

By late August, Los Alamos expected to deliver cores fast enough to support two to three atomic missions per week.

Crews were trained.

Aircraft were ready.

Atomic bombing was on the verge of becoming just another operational tool.

Imagine the alternate timeline.

The coup succeeds.

The emperor is silenced.

The third bomb falls on Tokyo around August 20.

Hundreds of thousands die—perhaps the emperor among them.

The fourth bomb falls days later.

The fifth soon after.

Japan’s governmental structure collapses completely.

The figure whose authority legitimized postwar reform vanishes.

Soviet forces occupy the north.

The U.S. –Japan alliance that would anchor the Pacific for generations never forms.

We do not live in that world.

But we almost did.

The story of the third atomic bomb forces a brutal reckoning.

Atomic weapons were not used twice because America ran out.

They were used twice because Japan surrendered just in time.

The infrastructure existed.

The will existed.

The bombs were coming.

Historians still argue whether the atomic bombs were necessary.

Some insist Japan was already defeated, strangled by blockade and Soviet entry.

Others point to the ferocity of internal resistance even after two bombs as proof that only overwhelming shock could end the war.

The truth, as always, is tangled in fear, uncertainty, and irreversible choices.

What is undeniable is this: once the machinery of destruction was set in motion, it did not stop on its own.

It required a human intervention—fragile, contested, nearly undone—to halt it.

The third atomic bomb never fell.

But its shadow remains, a reminder of how close history came to a far darker ending, and how easily the unthinkable can become routine once the switch is flipped.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load