The Terrifying Secrets of Pharaoh Khafre’s Ancient Technology: What Archaeologists Are Too Scared to Admit! 😱🔍

When we think of ancient Egypt, a few names immediately come to mind—Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid, and Tutankhamun, whose golden treasures dazzled the modern world.

Yet nestled between these iconic figures is Pharaoh Khafre, a ruler whose legacy is both magnificent and perplexing.

His reign during the Fourth Dynasty around 2570 BC produced monumental works that continue to baffle archaeologists, raising questions that resonate through the ages.

Khafre is not merely remembered as a king; he is seen as a pharaoh who may have left behind technology too advanced for his time.

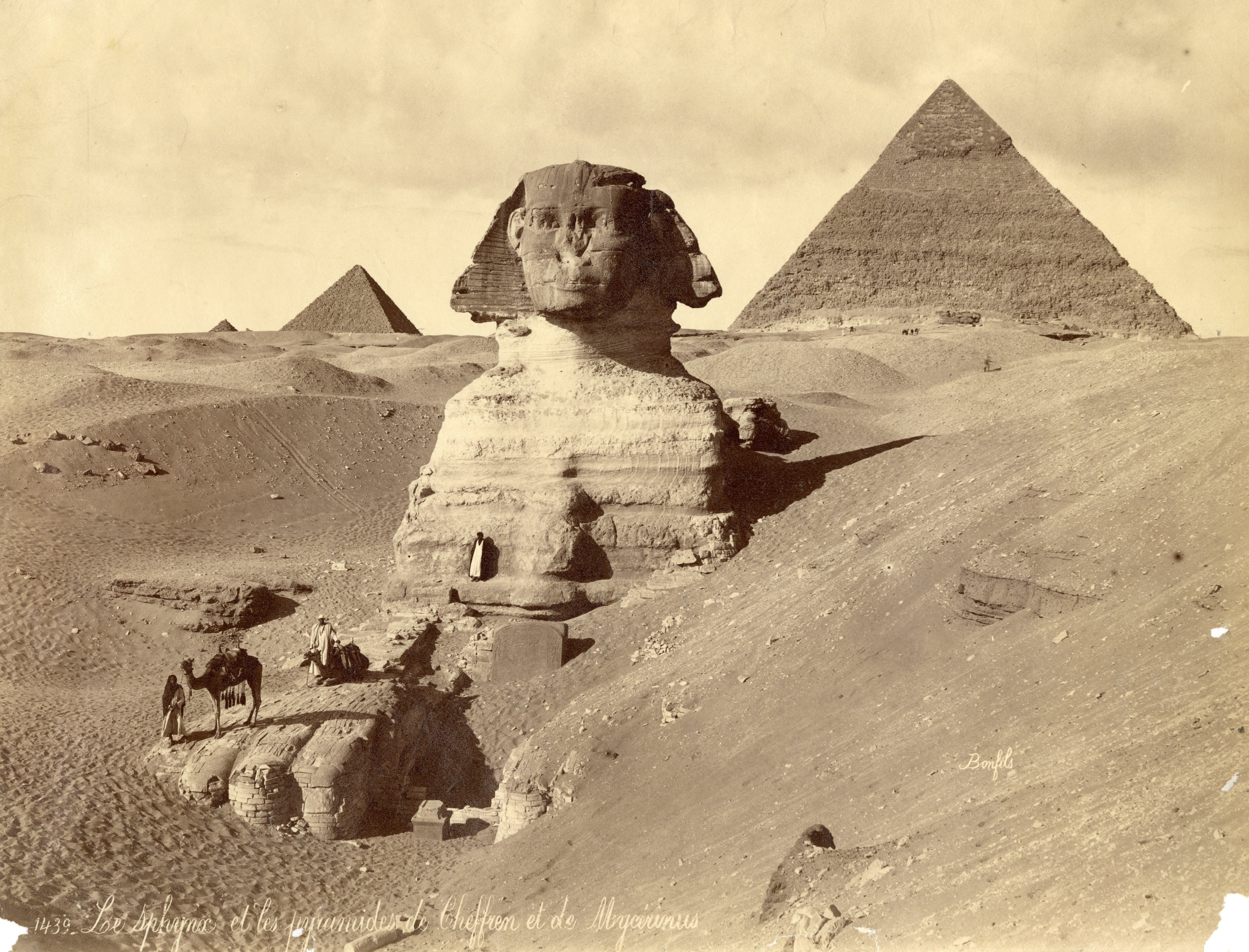

Khafre’s most notable achievement is his pyramid, the second largest at Giza.

At first glance, it appears to tower over Khufu’s Great Pyramid, an illusion created by its elevated position on higher ground.

This strategic placement ensured that Khafre’s monument would dominate the skyline, reaching a peak of 470 feet.

Originally covered in gleaming white limestone casing stones, remnants of which still cling to the summit, the pyramid once reflected the desert sun like a mirror.

The precision of its construction is almost unsettling; blocks weighing several tons were stacked with an accuracy that seems impossible given the primitive tools of the time.

The base of the pyramid is leveled to within mere centimeters, a feat modern engineers admit would require careful surveying even with today’s technology.

But the mysteries do not end with the pyramid.

Beneath Khafre’s monument lie unfinished underground chambers, suggesting careful planning and a hidden purpose lost to time.

If the pyramid itself is a testament to Khafre’s ambition, the Great Sphinx stands as his most enigmatic legacy.

Towering over the sands with its lion’s body and human face, the Sphinx has long been associated with Khafre, with mainstream archaeology claiming it was carved during his reign, its face modeled after him.

However, not everyone agrees.

Geologists like Robert Schoch and authors like Graham Hancock have pointed to patterns of erosion on the Sphinx that they argue are not the result of wind and sand, but of water.

This theory suggests an age thousands of years older than Khafre, hinting that he may have inherited and redefined a monument from a forgotten past.

The Valley Temple connected to Khafre’s pyramid adds another layer of intrigue.

Built from enormous limestone and granite blocks, some weighing over 200 tons, the temple defies expectations of what was possible with Bronze Age tools.

Inside, archaeologists discovered one of the most breathtaking statues of the ancient world—a diorite figure of Khafre seated on a throne, with the falcon god Horus perched protectively behind him.

The surface of this statue is polished to a degree of perfection that even modern stone cutters struggle to replicate.

How was such a feat achieved with copper chisels?

Even today, this statue radiates power.

Khafre stares forward with calm authority, his form untouched by time.

The diorite stone had to be transported from quarries in Nubia, hundreds of miles away, and then shaped with uncanny precision.

Egyptologists offer explanations in terms of time, labor, and skill, yet doubts remain.

Were Khafre’s builders simply more advanced than we imagine, or did they possess methods we have yet to uncover?

As night falls over Giza, Khafre’s pyramid and the Sphinx still command the desert, their silence louder than words.

These monuments are both testimony and question, triumph and riddle.

Archaeologists study the details, historians debate the evidence, and skeptics raise their voices.

Yet the mystery lingers: who exactly was Khafre? How did he achieve what he did in a world without iron, wheels for heavy loads, or modern machinery? The answers, if they exist, remain buried deep within the

stone.

Khafre’s pyramid at Giza may not carry the same fame as Khufu’s Great Pyramid, but it is just as puzzling.

Rising from its elevated plateau, it dominates the horizon with a defiant sense of permanence.

To the untrained eye, its placement looks coincidental, but archaeologists know better.

Khafre wanted his pyramid to compete with his father’s colossal masterpiece.

By situating it strategically, he created the illusion of superiority.

Even today, from certain angles, Khafre’s pyramid appears to be the tallest at Giza—a subtle act of ancient propaganda carved into the very landscape.

Beyond appearances lies engineering precision that continues to raise questions.

The base of Khafre’s pyramid stretches 700 feet on each side and is remarkably leveled to within a fraction of a degree—achieved without steel tools, modern surveying instruments, or advanced machinery.

How did the builders of the Fourth Dynasty achieve such accuracy? A small miscalculation would have thrown the entire structure off course, yet everything about this pyramid suggests careful planning and

execution.

The sheer mathematics embedded into the design feels like the work of engineers, not just laborers with copper chisels and ropes.

The construction blocks themselves are staggering.

Many weigh several tons, and some used in the temples around Khafre’s pyramid exceed 100 tons.

Moving them across the desert, aligning them precisely, and raising them to height would test the limits of any civilization.

The official explanation points to ramps, sledges, and manpower, but while these methods account for some of the work, they do not erase the nagging sense that something is missing from the story.

Was it merely ingenuity and brute force, or were the builders equipped with techniques that have since been lost?

Then there are the underground chambers.

While Khafre’s pyramid is less complex internally than Khufu’s, it contains passages and unfinished rooms cut directly into the bedrock.

Some of these chambers seem to have no clear function, leading scholars to speculate that they were abandoned mid-construction or had ritualistic purposes that remain unclear.

Nearby boat pits once held large ceremonial boats intended for the pharaoh’s journey in the afterlife.

The connection between the pyramid, the mortuary temple, and the valley temple reveals an integrated plan that goes far beyond the simple burial of a king.

The alignment of Khafre’s pyramid also deserves attention.

Like Khufu’s, it is oriented almost perfectly to the cardinal points.

Modern engineers using GPS and satellite technology are impressed by the precision.

For Khafre’s builders to achieve this without magnetic compasses or digital tools suggests a mastery of astronomy.

The Giza Plateau itself appears to be part of a grander design, with the three pyramids aligned with uncanny similarity to the stars of Orion’s belt, sparking ongoing debates.

Was this alignment deliberate? If so, what knowledge of the heavens did the ancient Egyptians truly possess?

Adding to the enigma are the casing stones that still cling to the peak of Khafre’s pyramid.

Unlike the stripped surfaces of Khufu’s and Menkaure’s pyramids, Khafre retains a crown of white limestone casing.

These stones once covered the entire monument, polished smooth to reflect sunlight so intensely that the pyramid would have shone like a beacon.

Standing before it, one can only imagine the awe it must have inspired 4,500 years ago.

But here again, the question arises: how were these massive stones cut, transported, and set with such accuracy that their joints are nearly invisible? Every detail of Khafre’s pyramid hints at planning and

execution on a scale that seems disproportionate to the tools and methods of the age.

The orthodox view insists this was the result of discipline, manpower, and time.

Yet the deeper one looks, the harder it is to shake the thought that something more was at play.

If Khafre’s pyramid was merely the product of sweat and stone, why does it still carry the aura of technological sophistication? Perhaps this is why scholars and alternative thinkers alike continue to scrutinize its

every angle.

The monument is not just a tomb; it is a puzzle that refuses to yield all its secrets.

If Khafre’s pyramid inspires awe, then the Great Sphinx inspires unease.

It sits silently at the edge of the plateau, staring eastward as though keeping vigil over the rising sun.

For centuries, the Sphinx has been an icon of mystery, its human face fused with the body of a lion.

Egyptologists have long attributed it to Pharaoh Khafre, arguing that the face is modeled after him and that the monument was carved from a single block of limestone during his reign.

But the Sphinx is not just another relic of the Old Kingdom; it is a riddle carved into stone, one that refuses to be solved.

At the heart of the debate is erosion.

Mainstream archaeology holds that wind and sand gradually shaped the Sphinx’s weathered body.

Yet geologists like Robert Schoch have argued otherwise.

They point to vertical fissures and undulating patterns that suggest water erosion.

If that is the case, the Sphinx would predate Khafre by thousands of years, built in an era when Egypt’s climate was wetter.

This single detail shifts the timeline dramatically, hinting at a civilization capable of monumental construction long before the dynasties of pharaohs.

Graham Hancock has repeatedly raised this question, suggesting that Khafre may not have built the Sphinx at all but rather inherited and recarved it.

Archaeologists push back, noting that there are no inscriptions or records directly tying the Sphinx to an earlier culture.

What we do have are causeways and temples linking it to Khafre’s pyramid complex, including the Valley Temple where his diorite statue was found.

This architectural relationship seems deliberate.

Still, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and the Sphinx remains an anomaly.

The possibility that it was recarved, perhaps from a lion-headed figure into Khafre’s likeness, continues to echo through academic and alternative circles alike.

Adding to the intrigue are the underground anomalies.

In the 1990s, geophysical surveys beneath the Sphinx revealed cavities and unexplained hollows.

Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities acknowledged their presence but insisted they were natural fissures.

Others were not convinced.

According to reports, the shapes detected resembled chambers, and legends of a hidden hall of records under the Sphinx only fueled speculation.

This mythical chamber, said to hold the lost wisdom of a forgotten civilization, has never been found.

Yet the rumors persist, and every new scan of the bedrock seems to revive the question of what lies beneath.

Even without hidden libraries, the Sphinx challenges our understanding of ancient engineering.

It was carved directly out of bedrock, its builders shaping a single massive block of limestone into the form we see today.

The sheer scale of this task raises questions about tools and techniques.

How did they achieve such symmetry? How did they align it so precisely to the east where the sun rises on the equinox? These are not minor details.

They suggest a knowledge of astronomy and geometry woven into the monument’s design.

And then there is the matter of restoration.

For thousands of years, the Sphinx has been battered by erosion, buried in sand up to its neck, and repaired in different eras.

Ancient inscriptions mentioned that even in pharaonic times, the Sphinx was already old and enigmatic.

Thutmose IV in the 15th century BC erected the Dream Stele between its paws after claiming the Sphinx appeared to him in a vision.

If Khafre truly built it, why did later rulers speak of it as though it had been standing long before their time? Today, the Sphinx remains both monument and mystery.

Its eroded body tells one story; its architectural links to Khafre tell another.

The geophysical anomalies beneath it whisper possibilities that fuel legends.

Scholars continue to defend the conventional timeline, but each new scan, each new observation leaves the door open just enough for doubt.

Was the Sphinx truly Khafre’s creation, or is it the surviving fragment of something far older, a legacy absorbed by his reign? Whatever the answer, one thing is certain: the Sphinx is not simply a statue; it is a

challenge, daring us to unlock its secrets.

Among the artifacts linked to Pharaoh Khafre, none is more striking or unsettling than the famous diorite statue discovered in his Valley Temple.

When it was unearthed, archaeologists realized they were looking at something that seemed to defy the limits of the ancient world.

The statue shows Khafre seated on a throne with the falcon god Horus perched protectively behind his head, wings spread as though shielding him.

It is a work of art, but more than that, it is a technological riddle that still provokes unease.

The choice of material alone raises questions.

Diorite is one of the hardest stones on Earth, registering above granite on the Mohs scale.

In today’s terms, it requires diamond-tipped tools to cut with ease.

Yet this statue, more than four millennia old, is carved with flawless precision and polished to a reflective sheen.

Egyptologists insist that copper chisels, dolerite pounding stones, sand, and endless patience could explain the craftsmanship.

However, when modern stonemasons are asked to replicate such work with the same tools, the results fall short.

The sharp lines of Khafre’s throne, the perfect proportions of his face, and the unblemished polish of the surface suggest something more than primitive techniques.

And it was not just one statue.

Dozens of diorite figures were found within Khafre’s complex, each representing hours, days, and years of painstaking labor.

Transporting the diorite itself would have been an undertaking of staggering proportions.

The quarries lay in Nubia, hundreds of miles south of Giza, meaning massive blocks of stone had to be dragged along the Nile, carved, and then polished in an age without steel.

This alone demonstrates the logistical might of Khafre’s reign.

Yet, according to reports, what disturbs some archaeologists is not simply the ability to move the stone but the ability to shape it with such near-mechanical precision.

The Valley Temple where the statue was found only deepens the mystery.

Its walls are built from limestone and granite blocks so massive that some weigh over 100 tons.

The joints between them are cut with a level of precision that recalls later Inca stonework, where huge blocks fit together so tightly that not even a sheet of paper can be slipped through the cracks.

The temple still stands in remarkable condition, its megaliths defying the erosion that has ravaged other monuments.

How did builders working with the simplest tools create such a structure? Why use blocks so unnecessarily large when smaller, more manageable stones would have sufficed? These are the questions that fuel

speculation.

While mainstream archaeologists reject this interpretation, they too admit that the Valley Temple is unique, its methods unlike those seen in other parts of the Old Kingdom.

This is why Khafre’s monuments attract such attention.

They are not just large; they are anomalous.

Adding to the unease are the symbolic elements woven into the statue.

Horus, the falcon god, clings to Khafre’s head, a reminder that the king was seen as divine.

But for some researchers, the symbolism takes on another meaning.

Was Horus not just a god of protection but also a guardian of knowledge? The statue, with its uncanny polish and enduring perfection, seems almost designed to outlast time itself.

It radiates permanence, as if Khafre wanted to ensure that his image—and perhaps the secrets of his reign—would never be erased.

Standing before the diorite statue today, visitors often remark on its lifelike quality.

The calm expression, the flowing muscles of the arms, the unyielding throne, all appear untouched by the millennia.

It feels less like an artifact and more like a message frozen in stone, daring us to ask how it came into being.

If Khafre’s builders truly accomplished this with only copper and stone, then their skills were nothing short of miraculous.

If not, then we are left with an uncomfortable possibility: that the ancient Egyptians may have inherited knowledge or tools that remain hidden from us.

For archaeologists, this duality is what terrifies.

Either Khafre’s craftsmen were vastly more advanced than we give them credit for, or his monuments preserve a glimpse of technology that does not fit the accepted timeline.

The diorite statue is not just art; it is evidence—evidence that forces us to confront the possibility that the past is far more complex than the story we have been told.

The terrifying revelation is that for decades, the monuments of Khafre have stood as symbols of Egypt’s glory.

But according to reports, they have also unsettled the very archaeologists who study them.

The sheer precision of the pyramid’s base, the megaliths of the Valley Temple, the mysterious erosion on the Sphinx, and the flawless polish of the diorite statue all combine into something that feels out of place in

the timeline of human development.

This is where the story begins to cross the line from admiration to fear because the evidence seems to whisper of technology that does not belong in the world of 2500 BC.

The phrase has been repeated often yet it lingers with particular weight in this case: archaeologists are terrified of Pharaoh Khafre’s ancient technology, and for good reason.

What terrifies them is not a machine left behind in the sand or a tool hidden beneath the pyramid.

It is the implication that the civilization of Khafre’s time may have possessed methods we cannot replicate even today.

To admit this possibility would be to acknowledge that history, as written in textbooks, might not be the full story.

Graham Hancock has spoken about this on several occasions, especially when addressing Khafre’s statues in the Valley Temple blocks.

He has been quoted as saying that it’s too advanced for its time, a comment that cuts to the heart of the matter.

The technology does not have to be mechanical in the way we imagine—no gears, no engines—but the level of skill, planning, and knowledge appears to leap centuries ahead.

The fact that diorite statues, aligned temples, and monumental engineering were all achieved during Khafre’s reign is enough to make even seasoned researchers pause.

The anomalies deepen the fear.

Geophysical scans beneath the Sphinx show cavities whose purposes remain uncertain.

Were they simply natural fissures, or were they deliberately carved to house chambers? Theories about a hall of records—whether mythical or not—grow from these unanswered questions.

The pyramids themselves, aligned with astonishing astronomical precision, seem to tie into a larger pattern that scholars struggle to explain away.

Each detail could perhaps be rationalized on its own, but together they form a picture that refuses to sit comfortably in the accepted narrative.

And that is why the terror is not about ghosts or curses; it is about history itself.

If Khafre’s monuments reveal technology that is too advanced for the Bronze Age, then what else have we overlooked? Could it be that Khafre’s builders inherited lost knowledge from an earlier civilization? Could

the erosion on the Sphinx and the anomalies beneath the plateau point to something far older than dynastic Egypt? These are questions that keep resurfacing precisely because the evidence does not go away.

For archaeologists, the possibility of rewriting history on such a scale is daunting.

For the rest of us, it is both thrilling and unnerving.

Khafre’s pyramid, his temples, his Sphinx, and his statue are not simply relics; they are messages carved into stone, reminders that the past may hold secrets we have only begun to grasp.

And that is why the phrase rings true: archaeologists are terrified of Pharaoh Khafre’s ancient technology.

And for good reason.

When the dust settles on Khafre’s legacy, what remains is not just stone but uncertainty.

His pyramid still towers over the desert.

His statue still radiates a timeless authority, and the Sphinx still watches the horizon.

Yet for all the excavations, surveys, and studies, no definitive answers have silenced the questions.

If anything, the more we learn, the more elusive the truth becomes.

Mainstream Egyptologists continue to defend the traditional narrative: Khafre ruled during the Fourth Dynasty, his pyramid was the second great achievement of the Old Kingdom, and the Sphinx was his

creation.

They attribute the precision of the monuments to skilled labor, organization, and time.

But this explanation does not erase the unease that lingers among those who look closer.

According to reports, even some within the field admit that the methods used remain incompletely understood.

Alternative researchers, meanwhile, see Khafre’s reign as a window into something far larger.

They argue that his monuments hint at knowledge that may not have originated with his dynasty at all.

The erosion patterns on the Sphinx, the astronomical alignments of the pyramids, the impossible craftsmanship of diorite statues—all of it suggests to them that Khafre may have inherited a legacy from a lost

civilization.

When Graham Hancock remarked that it was too advanced for its time, he was giving voice to this suspicion, a suspicion that continues to resonate far beyond academic circles.

The debate itself may be what defines Khafre in modern memory.

To some, he is a master builder whose engineers achieved the impossible with nothing more than stone, copper, and willpower.

To others, he is the inheritor of a mystery—a man whose monuments conceal knowledge older than Egypt itself.

In either case, his name has become synonymous not just with greatness but with the boundaries of human history.

What we do know is that Khafre left behind more than monuments; he left us a challenge, one that has endured for over 4,000 years.

His pyramid, his statue, and his Sphinx force us to confront uncomfortable possibilities, to ask whether we truly understand the story of civilization.

Whether Khafre was the pinnacle of Egyptian genius or the guardian of forgotten secrets, his monuments remain unyielding, daring us to keep searching.

And perhaps that, above all, is why his legacy feels so alive—not because we know everything about him, but because we still do not.

News

50 Cent EXPOSES Jay-Z: The Shocking Truth Behind His Super Bowl Snub—You Won’t Believe What He Said!

50 Cent EXPOSES Jay-Z: The Shocking Truth Behind His Super Bowl Snub—You Won’t Believe What He Said! 😱🏆 The drama…

50 Cent’s Ruthless Social Media Takedown: How He Handled Rivals Like a True Gangster—You Won’t Believe the Memes!

50 Cent’s Ruthless Social Media Takedown: How He Handled Rivals Like a True Gangster—You Won’t Believe the Memes! 💣😂 50…

Mase & Cam’ron Go to War with J Prince: The Shakur Beef Just Got Real—You Won’t Believe What They Said!

Mase & Cam’ron Go to War with J Prince: The Shakur Beef Just Got Real—You Won’t Believe What They Said!…

Eminem Speaks Out: ‘This White Boy Ain’t Checking In’—Is LA Really That Dangerous for Rappers?

“Eminem Speaks Out: ‘This White Boy Ain’t Checking In’—Is LA Really That Dangerous for Rappers? 🎤💥” Los Angeles has long…

Snoop Dogg Under Fire: DL Hughley Accuses Him of Being a ‘Fed Rat’—Is This the End of an Icon’s Legacy?

Snoop Dogg Under Fire: DL Hughley Accuses Him of Being a ‘Fed Rat’—Is This the End of an Icon’s Legacy?…

The Chilling Discovery of the Last Anunnaki King: Scientists Unearth Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History—Are We Ready for the Truth?

The Chilling Discovery of the Last Anunnaki King: Scientists Unearth Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History—Are We Ready for the…

End of content

No more pages to load