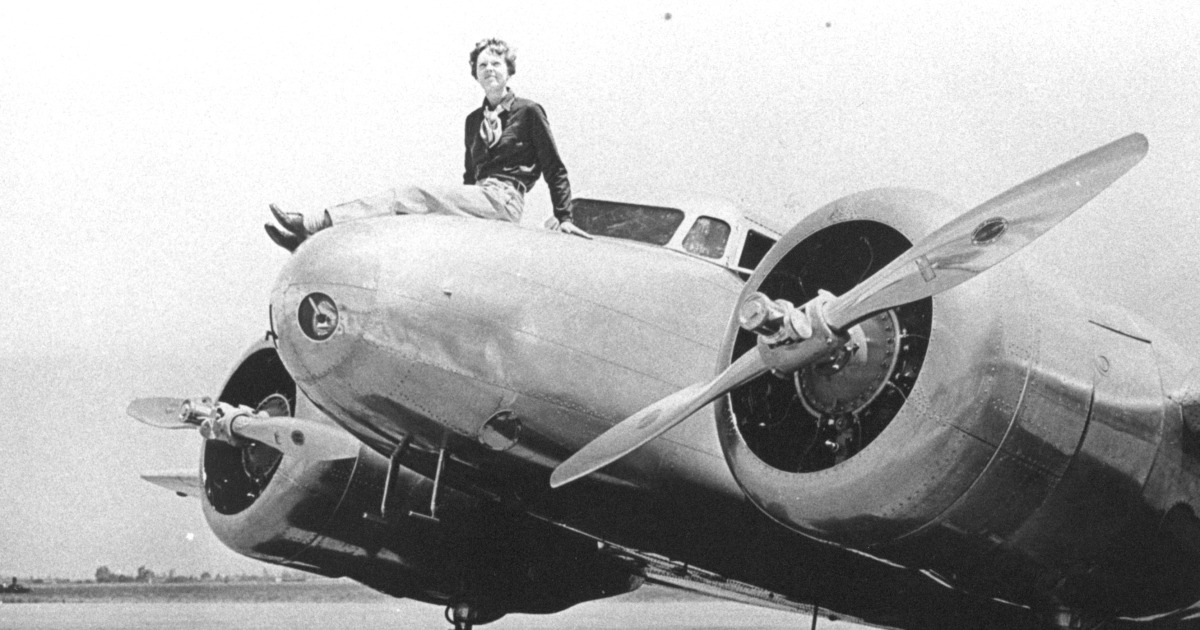

For most of his career, Ric Gillespie dismissed the Amelia Earhart mystery with professional skepticism.

To him, it was aviation folklore dressed up as science.

A missing airplane, a massive search area, 1930s technology, and decades of hindsight bias.

He’d heard the question countless times: when are you going to look for Amelia? His answer never changed.

There was nothing to find.

Or so he thought.

Everything shifted the day two members of his organization—retired military aerial navigators—asked for a meeting.

They weren’t theorists.

They weren’t romantics.

They were men trained in the same navigation methods used in the 1930s, men who understood celestial navigation not as a historical curiosity but as muscle memory.

When they began talking about sun lines, star fixes, and lines of position, Gillespie listened politely.

Then they mentioned Amelia’s final transmission.

“We are running on the line 157–337.”

Those words had been quoted endlessly, but rarely understood.

To most people, it sounded like confusion, maybe desperation.

To trained navigators, it was precision.

A line of position derived from a sunrise observation.

A north-south line cutting across the Pacific.

And Amelia was doing exactly what she should have been doing.

If she stayed on that line, flying north and south in search of Howland Island, she would eventually intersect land.

Not Howland—but another island.

An uninhabited one.

One that, astonishingly, no one had seriously searched with that assumption in mind.

Gardner Island.

Today known as Nikumaroro.

At first, Gillespie assumed this was just another recycled theory.

And in a sense, it was.

Because this wasn’t a modern invention at all.

It was the original conclusion of the U.S. Navy in the first days after Earhart vanished in 1937.

What changed everything was not speculation—but evidence that had been misunderstood, misfiled, and quietly ignored.

The radio calls.

After Amelia and Fred Noonan disappeared, something strange happened.

Radio operators across the Pacific began hearing transmissions on Earhart’s frequencies.

Weak at first.

Fragmented.

But unmistakable.

The Coast Guard heard them.

The Navy heard them.

Professional operators logged them carefully.

Even more unsettling, civilians in North America—people with no reason to be listening—began stumbling across her voice on shortwave radios.

This made no sense.

The Pacific operators, listening on Amelia’s primary frequencies, heard faint signals.

The farther they were from her, the weaker the transmissions became.

That was expected.

But in the continental United States and Canada, people were hearing her clearly, sometimes as if she were nearby.

The explanation lay in physics, not fantasy.

Amelia’s radio didn’t transmit on just one frequency.

It produced harmonics—multiples of her primary frequencies.

Those harmonics bounced off the ionosphere, skipping unpredictably across the globe.

If you happened to be where they came down, you could hear her from thousands of miles away.

Not because she was close—but because the sky carried her voice.

Meanwhile, Pan American Airways was quietly doing something extraordinary.

Pan Am had built radio direction-finding stations across the Pacific—on Oahu, Midway, Wake Island—guiding their transoceanic Clipper flights.

They were hearing the signals too.

And they weren’t guessing.

They were taking bearings.

Those bearings crossed.

And where they crossed was not open ocean.

They converged near a small, forgotten island: Gardner Island.

The Navy considered the possibility.

Maybe Amelia wasn’t floating at sea.

Maybe she was on land.

And then came the insight that made the theory unavoidable.

Lockheed engineers weighed in.

If the radio transmissions were continuing night after night, then the airplane could not be submerged.

The radios would have been flooded.

Beyond that, the battery powering the transmitter would have died quickly unless it was being recharged.

And the only way to recharge it was to run the right-hand engine—the one with the generator.

Which meant the airplane had landed.

Wheels down.

Upright.

Not crashed.

Not ditched.

Landed.

And the airplane had to be on solid ground, because you cannot run an engine with the aircraft resting on its belly.

That realization forced a conclusion the Navy could not ignore.

Amelia Earhart was alive after July 2, 1937.

She was calling for help.

And she was on Gardner Island.

So the Navy acted.

They dispatched the battleship USS Colorado from Pearl Harbor—2,000 miles away.

It took a week to arrive.

By the time it did, the radio signals had stopped.

On the morning of July 9th, three catapult-launched floatplanes flew over Gardner Island.

They saw no airplane.

Dense vegetation covered much of the island.

The beaches were narrow, steep, and unforgiving.

They noted signs of recent habitation—but dismissed them.

They assumed the signs were from native work parties harvesting coconuts.

What they didn’t know was critical.

Gardner Island had not been inhabited or worked since 1892.

There should have been no signs of recent human presence at all.

But they didn’t know that.

They saw no airplane.

And so they made a fatal assumption.

The radio calls must have been hoaxes.

Or misunderstandings.

Or wishful thinking.

Amelia must have gone down at sea after all.

They left.

The rest of the search focused on open ocean.

Floating debris.

Life rafts.

Nothing was found.

Eventually, the Navy closed the case with the explanation that became history: crashed and sank.

But that conclusion only worked if you ignored the radio evidence.

The direction-finding data.

The engineering realities.

The navigation logic.

And the fact that Amelia said exactly what she was doing—and did exactly what she should have done.

Decades later, Ric Gillespie and his team began returning to Nikumaroro.

They found things that shouldn’t have been there.

Pieces of aluminum not from known wrecks.

Artifacts consistent with 1930s American equipment.

A woman’s shoe sole.

Sextant-related fragments.

Human bones discovered in 1940 that were dismissed at the time—but later measurements suggested they belonged to a woman of Earhart’s height and build.

None of it proved the case alone.

But together, the evidence told a story far more coherent than “tiny island, big ocean.”

Amelia Earhart did not vanish.

She navigated.

She landed.

She survived—for days, perhaps weeks.

She called for help until the radio went silent.

And then, on a remote atoll at the edge of the world, she was missed by a search that looked directly at her and didn’t understand what it was seeing.

The tragedy isn’t that she disappeared.

It’s that she was found—and dismissed.

The mystery of Amelia Earhart was never about the ocean.

It was about assumptions.

About what people believed was possible.

About how easily evidence can be ignored when it doesn’t fit the story we expect.

And now, nearly a century later, the line she flew—the 157–337 line—still cuts across the Pacific, pointing not into emptiness, but toward land.

Toward an island.

Toward a woman who did everything right… and waited.

The radio kept talking.

We just weren’t listening.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load