🍷 ‘It Wasn’t Poison…’ — The Disturbing Truth Buried in Beethoven’s DNA That Scientists Kept Quiet for 198 Years

The night Beethoven died, the city of Vienna was caught in a storm.

Thunder rattled the windows.

Wind howled through the cobblestone alleys.

And somewhere inside a modest apartment, the greatest composer who ever lived lay fading.

Witnesses later claimed that a bolt of lightning struck just as he lifted his hand — as if conducting his own final movement.

It was a story too perfect to question.

Yet behind that myth, his body was a battlefield.

His skin jaundiced, his stomach swollen with fluid, his eyes sunken and hollow.

To those at his bedside, it was a tragic end.

To modern scientists, it was a puzzle waiting two centuries to be solved.

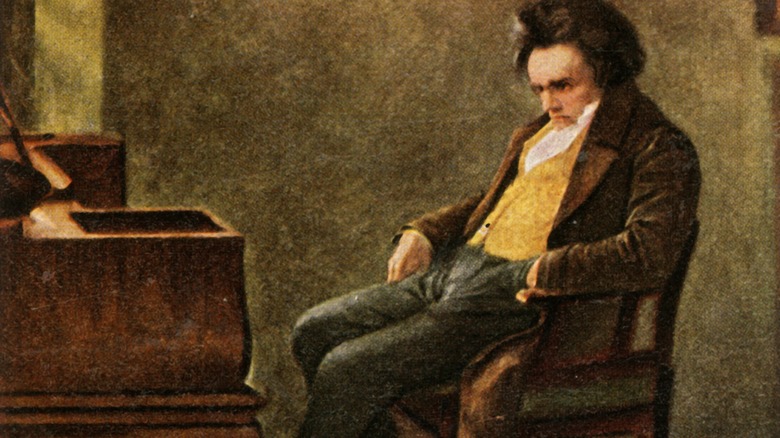

Beethoven had been sick for years.

Letters he wrote in his thirties already speak of “gut pains that tear me apart” and “constant sickness of the bowels.

” He was losing his hearing — the one thing a composer cannot lose — and the isolation nearly broke him.

He turned inward, toward music, toward defiance.

But his body was falling apart.

By his fifties, his face was bloated, his skin yellow.

Every meal caused agony.

The wine he loved became his enemy, though he never stopped drinking it.

When he finally died in 1827, the autopsy shocked his doctors.

His liver was shrunken and scarred — a textbook case of cirrhosis.

His spleen and pancreas were inflamed, his intestines ulcerated.

They could see the destruction, but not the cause.

The theories began almost immediately.

Some said it was alcoholism.

Others whispered about syphilis, mercury, even deliberate poisoning.

But the theory that captured the public’s imagination — and held it for generations — was lead.

Beethoven’s favorite wines, historians said, were stored in lead-sealed casks.

The heavy metal seeped into every glass he drank.

The poison theory was perfect — poetic, tragic, scientific.

It explained everything.

Until it didn’t.

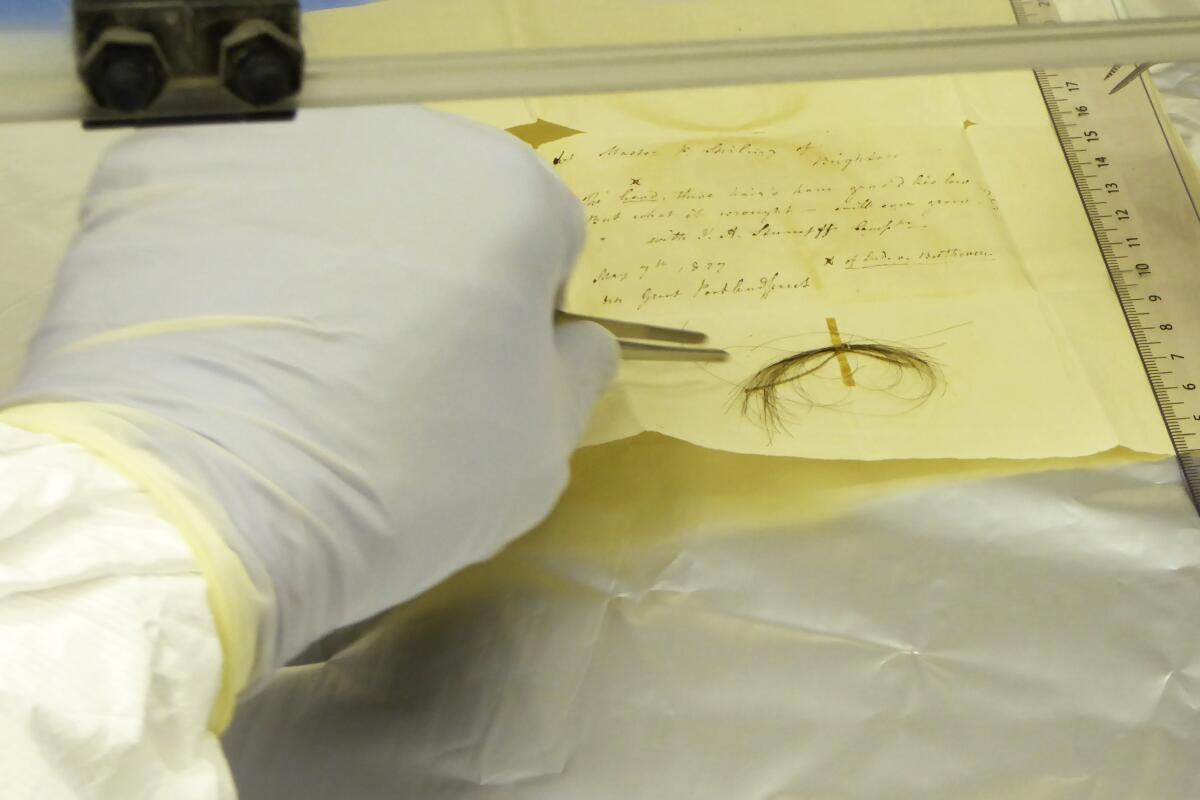

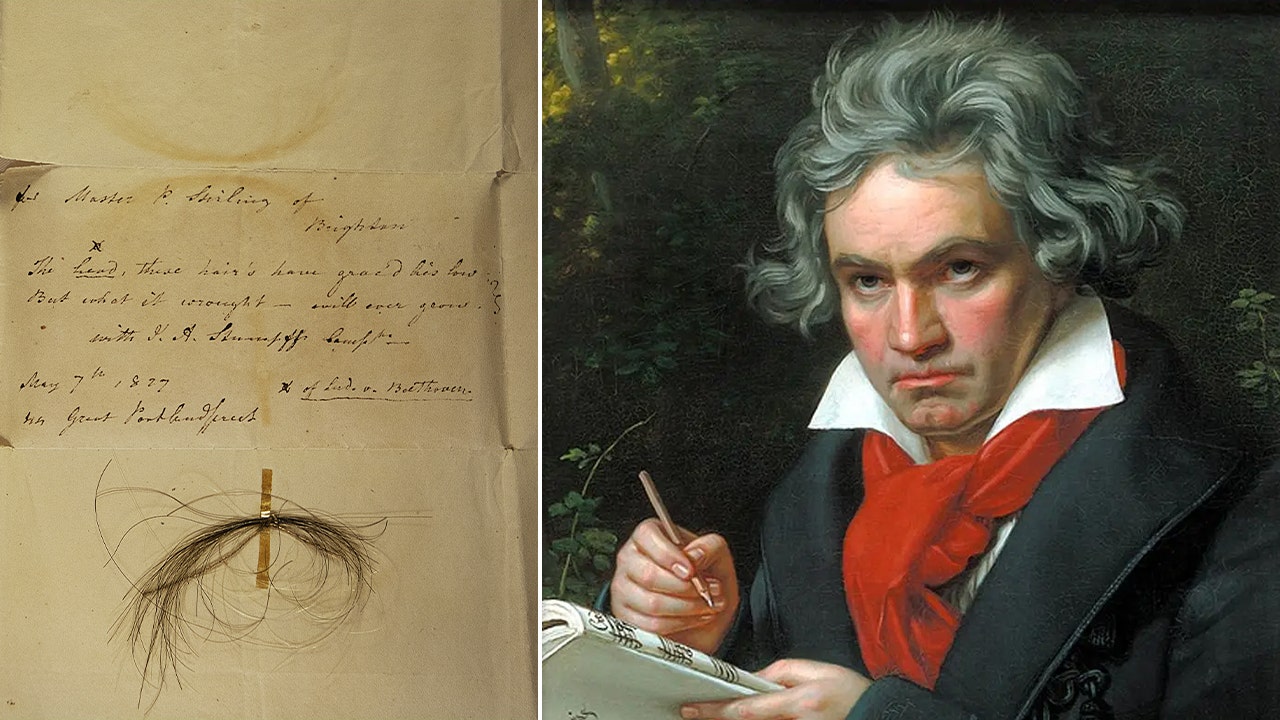

When scientists in the 1990s tested a lock of Beethoven’s hair, they found lead levels 100 times higher than normal.

The world gasped.

The case was closed.

The newspapers called it “Beethoven’s Fatal Wine.

” But decades later, when DNA technology advanced, that same lock — the famous “Hiller Lock” — was tested again.

And the results were humiliating.

The hair wasn’t Beethoven’s.

It wasn’t even male.

It belonged to a woman of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

For nearly 200 years, the entire world had been studying the wrong hair.

Every toxicology study, every headline, every documentary built on a lie.

The great “lead poisoning” mystery was nothing but scientific fan fiction.

That’s when researchers turned to Beethoven’s real hair — authenticated through genetic sequencing in 2023.

For the first time, science wasn’t working off relics or rumors.

It was working off Beethoven himself.

Eight locks of hair from museums and private collections were tested.

Only five matched the same mitochondrial DNA — the maternal signature passed down through generations.

Those five were real.

Beethoven’s true hair.

The others were impostors, fakes, historical illusions.

From those fragile strands, researchers pulled the truth — molecule by molecule.

Beethoven’s genome was fragmented, degraded, but recoverable.

They rebuilt it like a musical score reconstructed from torn pages.

And when the full genetic sequence came into view, the story it told was devastating.

Beethoven’s DNA revealed multiple variants of genes — PNPLA3 and HFE — both linked to chronic liver disease.

These mutations don’t guarantee illness, but they make the body frighteningly vulnerable.

In other words, Beethoven’s biology was a loaded gun, waiting for the right trigger.

The next discovery was worse.

In one of the verified hair samples, scientists detected fragments of the hepatitis B virus — the pathogen that attacks the liver, silently and relentlessly.

It was like finding a ghost in the bloodstream of history.

Beethoven hadn’t just suffered from bad luck or bad wine.

He’d been infected with one of the deadliest viruses known to medicine.

And in 1827, there was no treatment, no diagnosis, no concept of what a virus even was.

He was dying of a disease no one could name.

The puzzle pieces clicked into place with cruel precision.

Genetic vulnerability.

Chronic infection.

Heavy drinking.

Together, they formed a fatal triangle that medicine of his time could never have untangled.

The virus inflamed his liver.

His genes made his organs weaker.

The alcohol finished what biology began.

It wasn’t a poison from outside that killed him.

It was a war inside his own cells.

For historians, the implications were staggering.

Every symptom Beethoven ever described — the yellow skin, the fatigue, the constant abdominal pain — lined up perfectly with modern profiles of hepatitis-induced liver failure.

The manic bursts of energy, followed by crushing depression, could have been the result of hepatic encephalopathy — the brain fog and mood swings caused by toxins his liver could no longer filter.

Even his volatile temper, once chalked up to artistic temperament, may have been biochemical chaos.

Beethoven wasn’t cursed.

He was sick.

And for the first time, science could prove it.

The revelation was both triumphant and tragic.

For 198 years, the world romanticized Beethoven’s suffering — the deaf composer raging against fate, crafting immortal beauty from pain.

But his real story was more brutal, more human.

His death wasn’t a poetic metaphor.

It was a medical catastrophe.

A man with the wrong genes, in the wrong century, living with a virus that would take another 150 years for humanity to even understand.

And the irony? If Beethoven were alive today, he might have survived.

Modern medicine could treat hepatitis B, manage his liver condition, and possibly even reverse the damage.

The man who composed Ode to Joy could have lived to hear it performed.

That realization hit like a minor chord beneath his myth — the sound of possibility lost.

Still, in death as in life, Beethoven refused to fit neatly into the categories we built for him.

His DNA even revealed another twist — a genetic surprise suggesting that somewhere in his paternal line, an affair or secret birth had broken the Beethoven bloodline.

His Y-chromosome didn’t match that of living male relatives descended from his father’s family.

Even his ancestry was rewritten.

Every cell, every sequence told the same story: the legend we thought we knew was never the full truth.

So what killed Beethoven? Not poison.

Not malice.

Not fate.

But a perfect biological storm — genes, infection, and human habit colliding in slow motion.

The result wasn’t mythic.

It was mercilessly ordinary.

The kind of death that happens every day, to people who will never know their DNA betrayed them.

And maybe that’s what makes it worse.

The idea that even genius can’t outthink biology.

That the man who composed the music of gods died from the same fragile human design as the rest of us.

When the DNA study was published, it didn’t just solve a mystery.

It stripped away the romance.

It revealed a truth too real to ignore.

Beethoven, the immortal composer, wasn’t taken by divine tragedy.

He was undone by the same forces that govern us all — the chemistry of life, the inevitability of decay, the silence that waits for everyone.

And yet, in that silence, his music still plays.

Because if science finally gave us the answer to how he died, his art still answers why he lived.

In every rising crescendo, every defiant chord, you can still hear it — the sound of a man outlasting his own body.

The body failed.

The music did not.

So when you next hear Ode to Joy, listen closely.

Beneath the triumph, beneath the brass and the chorus, there’s a quieter voice — a whisper from his DNA itself, saying: This is how far I got before the body gave out.

And perhaps, that’s the most human symphony of all.

News

“Not Human. Not Neanderthal.” The Greek Skull That Shouldn’t Exist—and Why Scientists Are Losing Sleep

🧠🚨 “Not Human. Not Neanderthal.” The Greek Skull That Shouldn’t Exist—and Why Scientists Are Losing Sleep 😱🪨 The cave was…

“This Shouldn’t Be There”: NASA Rover Spots a Strange Symbol on Mars—and Scientists Are Losing Sleep Over It

🛸 “This Shouldn’t Be There”: NASA Rover Spots a Strange Symbol on Mars—and Scientists Are Losing Sleep Over It 😳🔴…

“It Shouldn’t Exist”: Mexico’s Colossal Stone Faces Just Revealed a Secret That Rewrites Ancient History

🚨 “It Shouldn’t Exist”: Mexico’s Colossal Stone Faces Just Revealed a Secret That Rewrites Ancient History 🗿⚡ It starts with…

“Frozen Faces That Still Breathe”: The Ice Mummies of Siberia That Terrified Scientists and Unlocked a Hidden Civilization Beneath Antarctica

🧊 “Frozen Faces That Still Breathe”: The Ice Mummies of Siberia That Terrified Scientists and Unlocked a Hidden Civilization Beneath…

Experts Just Found a SECRET CODE Hidden in Da Vinci’s Last Supper — And It Changes Everything You Thought You Knew!

🕵️♂️ Experts Just Found a SECRET CODE Hidden in Da Vinci’s Last Supper — And It Changes Everything You Thought…

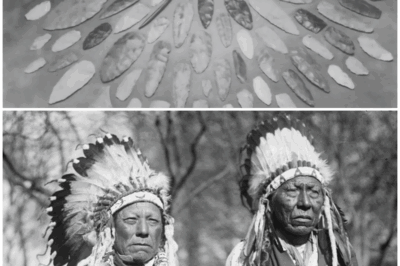

DNA of The ONLY Clovis Ever Found Changes Everything We Know About The First Americans!

DNA of The ONLY Clovis Ever Found Changes Everything We Know About The First Americans! The story begins in the…

End of content

No more pages to load